Marion County has typical urban levels of soil contamination, and potable groundwater is readily available. Several larger contaminated soil sites (brownfields) following EPA redevelopment guidelines, including a recent EPA-conducted clean-up in the are for soil lead contamination.

Several areas of groundwater contamination are being monitored closely. The origin, location, and extent of soil and groundwater contamination within Marion County is derived from: the soil types and underlying at the location; the present and past land uses at the location; the lack of, or amount of, pollution prevention practiced at the location.

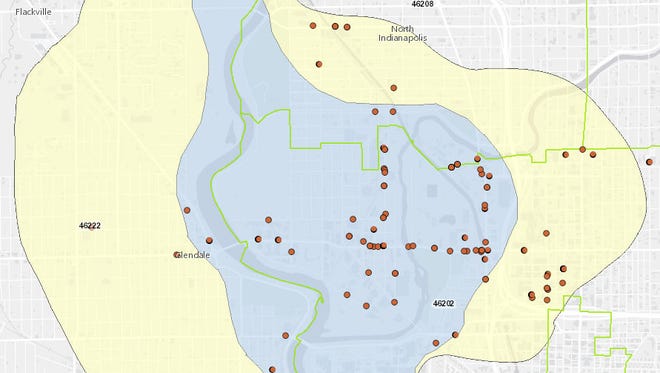

Similar to other industrialized urban areas, Indianapolis has a myriad of individual sites and even entire portions of the city that are contaminated to some degree. The origin of the contamination ranges from small gasoline stations to manufacturing sites to large Superfund sites such as Southside Landfill. While contaminated sites occur in all portions of the county, the area south and west of downtown from to Washington Street is by far the most heavily contaminated due to the age, types, and concentration of industries, as well as and the high permeability of the saturated outwash deposits (material that washed out from the margins of a glacier by meltwater).

Nearly every industrial site has had some sort of chemical spill; however, most are typically small. Much industrial (manufacturing) contamination is either older or has been discharged to the White River or the atmosphere and not directly to soil. The Marion County CERCLIS (Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Inventory System) list developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had 97 older industrial sites listed in July 1992, but most of these require no further action. In 1992, there were at least 755 sites that stored one or more chemicals requiring Community-Right-to-Know reporting (SARA Title III), and at least 195 sites that stored Extremely Hazardous Substances (EHS). Most storage is within specially designed areas.

One designated EPA Superfund site is located on the near southside—, which has chemical releases migrating into groundwater. Two other sites have been cleaned up since 2000 and removed from the Superfund list. One of these is the Southside Landfill, which is built on outwash and is immediately adjacent to White River. A landfill has been in operation at the site for several decades, and it contains nearly any chemical or waste ever available to citizens or industries within Marion County. The landfill is known to have subsurface contamination moving toward the river. This movement has been delayed/retarded by the late-1980s installation of a subsurface cement grout curtain around the landfill.

Underground Storage Tanks (USTs) containing petroleum hydrocarbons are the most widespread potential contamination point sources within Marion County. In January 2019, there were 4,135 sites registered with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management with one or more tanks, and 176 tanks were reported to have leaked some amount between October 1, 2017, and September 30, 2018. Most USTs that have leaked have affected only a very small area adjacent to the tanks. These soils are typically either excavated and disposed of at landfills or are cleaned on-site through aeration and/or bioremediation methods. Some of the largest known UST problems involve large bulk storage facilities of refined products and unrefined crude oil.

Numerous landfills exist within Marion County in addition to the Southside Landfill. These include the older and now closed Julietta, Banta Road, and Southport Road municipal solid waste landfills. Many construction-demolition debris landfills are scattered across the county. These are mainly located within old sand and gravel pits near White River and more recently in borrow pits along the interstate highways. Many former along streams and rivers were filled (“reclaimed”) with all manner of wastes early in the city’s history.

Several highway and street salt storage piles have contaminated soil and groundwater around the facilities. In a few cases, this has caused residential water wells to become unfit for human use. Salt contamination along roadways and ditches can be a localized problem with vegetation kills and surface runoff to streams.

Septic systems have long been recognized as a major localized, yet a really dispersed source of biologic contamination in the form of fecal coliforms and E. coli bacteria. While these materials are biodegradable, they can have significant impacts in the immediate system area, especially in larger unsewered subdivisions with water wells or those that discharge into surface water. Many of these septic systems were taken offline by 2018, with those neighborhoods being connected to the city sewer system.

Recently, the amount and areal extent of soil and groundwater contamination caused by “nonpoint sources” has been recognized. These sources included hydrocarbons and other fluids from motorized vehicles, road salt, random chemical spills, agricultural chemicals, and contaminants deposited locally by wind and precipitation. One with clear negative impacts on human health is soil lead contamination from numerous sources. The amount of contamination varies greatly on a site basis.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.