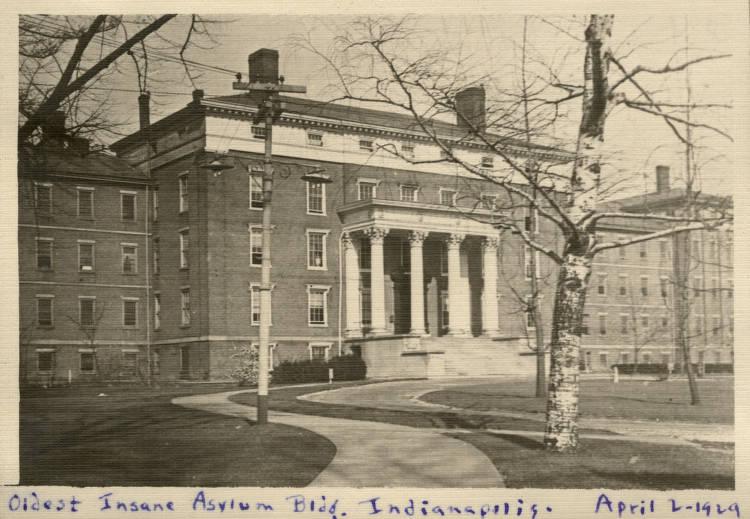

In 1844, the famous reformer Dorothea Dix inspected almshouses and jails near Indianapolis that housed mentally ill paupers. Her subsequent report helped persuade state legislators to approve funding for a “State Lunatic Asylum” to be located near Indianapolis so that legislators could oversee its operation. Even before its completion in 1848, the new institution’s name was changed to the Indiana Hospital for the Insane. When the state legislature approved the establishment of three other regional psychiatric institutions in 1889, it became the Central Indiana Hospital. In 1929, its name was changed to Central State Hospital.

The 19th century was a turbulent period for the new institution. Like most such hospitals, Central State was chronically underfunded and poorly staffed. It admitted its first five patients on November 21, 1848, and expanded to 300 within 10 years.

When the legislature failed to allocate funds for the hospital in 1857, its superintendent, James Athon, sent all patients back to their home counties. An appropriation was finally approved that autumn and the hospital reopened. Similar events recurred in 1863-1864, but this time monies for operating expenses were allocated from the general fund of the state and no inmates had to be discharged. Central State lacked a department for women until 1884. That year, it added its first female physician, Sarah Stockton, to the staff.

Nineteenth-century patients were offered a range of therapies. There was an initial commitment to the most popular antebellum treatment, moral therapy. As the hospital grew, its doctors increasingly relied on drugs to calm patients and substituted classification by ward for individualized treatment plans. Patient employment in farm and domestic work also was considered therapeutic. In 1883, a new superintendent, , burned the hospital’s mechanical restraints in a public bonfire. He was later fired and the hospital resumed its reliance on sedatives and restraints to control patients.

Fletcher’s dismissal suggests the extent to which, during the 1880s, Central State Hospital became a battleground for the partisan politics of the period. Its location in Indianapolis made the institution particularly vulnerable to political pressure. Increasingly, staff positions were awarded for political loyalty rather than professional competence. Superintendents changed with the governor.

Eventually, in 1889, the legislature established a bipartisan Board of State Charities to oversee Indiana benevolent institutions. At the beginning of the 20th century, Indiana had four mental hospitals—Central (1848), Logansport (1888), Richmond (1890), and Evansville (1890)—scattered geographically so as to meet the needs of the various regions of the state. Central State, with an average population of 1,800, was by far the largest. The others held from 400 to 800 patients.

Under the leadership of Superintendent , Central State established a new pathology department in 1895, which through its research and lectures subsequently attracted international attention. Such innovations, however, did not solve the perennial problems of patient abuse, overcrowding, and inadequate therapies. Throughout the 20th century, periodic newspaper exposés shocked politicians and taxpayers but produced few substantive reforms.

During the “deinstitutionalization” movement of the 1960s, Central State Hospital discharged many of its long-term patients and became involved in a broad range of mental health programs. During the early 1990s, several patient deaths at the hospital once again brought Central State to public notice and led to the decision of the administration of Governor Evan Bayh to close the hospital in 1994.

After the hospital closed, several proposals surfaced for the reuse of the property, which was owned in part by Saint Anthony Catholic Church and All Saints School. In 2003, the City of Indianapolis bought the 160-acre campus from the state, and the Indianapolis Police Department established horse stables for its mounted patrol on the western edge of the property.

IPD also used the 120-year-old laundry building for its motor pool. The city used other empty buildings for law enforcement and firefighting training. Diving clubs and Navy Seals practice on trampolines in the Bahr Building, built in 1960 and used as a treatment center for teens and children. The established in the 1896 Old Pathology Building in 1969, has been in continuous operation, with lease options that total 198 years.

In 2007, a group of investors began to make concrete plans for the redevelopment of the property for residential and commercial use, although the recession in 2008 stopped progress for several years. In the decade beginning in 2010, the city invested $8 million into rebooting the property’s development, with the goal of recouping the money through TIF properties (tax increment financing). The plans went under the name Central Greens, but the name Central State persisted as people naturally identified the area more closely with the hospital.

Eventually, developers and the city embraced the history of the hospital, and new streets and housing developments were named to reflect the long-demolished Women’s Department building. The building’s style was memorialized in the name Kirkbride Way and its nickname, Seven Steeples, became Steeples Boulevard. An apartment complex named The Steeples on Washington opened in 2012.

The Academy West, a charter elementary school, opened in 2014 on the southwest corner of the property. By 2017, all of the historic structures that remained of the hospital except for the 1886 power plant and the Cold Storage Building were rehabilitated and occupied. Project One, in the cafeteria building, and Ignition Arts, the laundry building, are both fabrication and design studios. People for Urban progress entered the Carpentry Building in 2017.

Reverie Estates repurposed the 1899 dining hall and the former Employee/Administration Building as a meeting venue and co-residential housing, respectively. Villages of Central State are newly built residential homes along Central Greens Boulevard. MI Homes constructed two single-family residential housing divisions, 58 Bahr and Bolton Square, that roughly occupy sites of former hospital buildings, both named for individuals important to the history of the hospital ( and ). The adjacent city park is also named for Bahr, the former superintendent.

A portion of the acreage left behind by the demolition of Seven Steeples will remain a green space as part of the Indiana Medical History Museum, with the establishment of the Indiana Native Tree Arboretum in 2017 and the Indiana Native Prairie Patch, planted in 2018. The northwest portion of the property continues to house the Mounted Patrol facilities and the K-9 police dog training center.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.