Although Indiana’s early school laws made no reference to race, few African American children attended local township schools, relying instead upon churches and sympathetic Quakers to obtain an education. In 1847, Black residents meeting in Indianapolis unsuccessfully petitioned the state legislature to provide school funds for their children: “The white people of this state ought not to reproach us with being ignorant, degraded, and poor… while they tax our property… to educate their own children while denying to ours the benefits and blessings conferred by this taxation.”

An 1855 law exempted Black-owned property from taxation for local schools, but by the 1860s there were four private day schools and five Sabbath schools for African Americans in Indianapolis, including those sponsored by of and by the AME Church, both of which dated from the 1850s.

1866-1920

Following the Civil War, Indiana’s legislature faced mounting pressure to fund Black schools. Indianapolis School Board Commissioner Dr. Thomas B. Elliott reported in 1866 that “the colored people of the state and city have… been deprived of advantages of the school fund, or any privileges of the schools… [and] should receive the benefit of our common school system.”

Superintendent likewise noted the “very creditable” proportion of Black children attending subscription schools, and that their schools were “maintained under great disadvantages—without the generous sympathy of the public generally.” The city provided a building in Ward Four for Black students with Broyles as principal. and his brothers Benjamin and James also served as principals of other Black schools.

During and after the Civil War, public opinion gradually turned in favor of state funding for African American schools. The Indiana Colored Equal Rights League, the Indiana State Teachers Association, the Indianapolis school board, the state superintendent of public instruction, and Governor all recommended educational appropriations for African American children.

In 1869 state representatives approved legislation requiring separate schools for Black children when numbers were sufficient and allowing trustees to make alternate arrangements when there were too few Black pupils to organize a separate school. The law also placed white- and Black-owned property on an equal basis for the assessment of school taxes.

Communities without separate schools faced another dilemma. In , an African American parent sought to enroll his children in a white school and was denied. Claiming a violation of both the 14th Amendment and the Indiana Constitution, the plaintiff, a Mr. Carter, father of two school-aged children, won his case in Marion County Superior Court. In (1874), the Indiana Supreme Court reversed the lower court decision and interpreted the 1869 school law to forbid African-American pupils from attending schools with whites under any circumstance.

The General Assembly amended the school law in 1877 and allowed Black children into white schools when no separate school existed. With some exceptions, however, most African American children in Indianapolis attended segregated elementary schools.

1920-1949

The influx of southern Blacks into Indianapolis after World War I placed additional strains on the community and its school facilities. Increased enrollment forced Black elementary children to attend half-day sessions. By 1925, 1,000 African Americans attended the city’s four high schools.

This rapid growth in the city’s Black population led multiple groups in the city to call for separate schools. With the backing of civic leaders, parents’ organizations, women’s groups such as the , and the , the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners recommended the construction of a separate high school for Black students late in 1922. In this conservative social economic and political atmosphere, the gained control of the offices of the mayor and city council in the election of 1925, and a slate of school board candidates supported by segregationist community organizations and the Klan also won in the election. Members of this board appropriated funds for the construction of the new high school. The all-Black opened in 1927 and kept education facilities racially separate until the passage of the state’s 1949 anti-segregation law.

Ignoring pleas from the Black community, school commissioners redrew district lines for the new Black schools and required all-Black high school students to attend Crispus Attucks regardless of where they lived in the city. Under a 1935 state law, however, the Indianapolis school board provided transportation for Black pupils attending separate schools.

While segregated schools became a way of life in Indianapolis, developments elsewhere foreshadowed local changes. Labor shortages during World War II brought a reevaluation of the role of African Americans in the economy. Business and labor leaders worked with African American leaders to establish the Indiana Bi-racial Cooperation Plan (1940) to improve job opportunities for Blacks. In June 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Fair Employment Practices Committee, designed to end job discrimination. As wartime labor needs opened employment opportunities for Blacks in positions previously reserved for whites, African Americans championed the idea that their children deserved much better schooling than they were getting in local segregated schools.

The campaign to end school segregation intensified in the 1940s as critics labeled Indianapolis the largest northern city with a segregated school system. The school board fought desegregation because of “current local practices,” the anticipated increased capital outlay for buildings, and the potential dismissal of tenured Black teachers within the system.

To prevent total desegregation, in 1948 the school board transferred 100 Black students to all-white schools, which generated protests by white parents. , a Black attorney and former state legislator, appeared before the school board in September 1948, stating, “We have waited, pleaded and worked on this particular problem for more than ten years;… it is high time the school board throw out and abolish its old Klan policy of 1926.”

1949-1970

Assisted by civic, church, and labor groups, the local lobbied to secure passage of the state’s 1949 desegregation law (House Bill 242), which provided “equal, non-segregated, non-discriminatory educational opportunities and facilities for all.” The Indianapolis school board announced a plan for compliance and abolished separate elementary school districts based on race.

Beginning in 1951, Black teachers were assigned to white schools, and by 1953 the process of desegregating the city’s high schools was completed. Nevertheless, many white residents resisted attempts to integrate the schools.

Reinforcement of Indiana’s desegregation law came in the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision , which declared racially separate schools unconstitutional. Following the ruling, Indianapolis African Americans attempted to find housing in white neighborhoods and enroll their children in white schools.

Creating single-race residential school districts, however, was one of the most effective means of maintaining segregated schools. Therefore, housing quickly became the pivotal issue in the separate school debate, with claims that property owners and real estate agents colluded to exclude Black residents from particular neighborhoods. Thus, segregated schools continued in Indianapolis for several years beyond 1954.

By the 1960s, critics condemned the (IPS) for perpetuating racial segregation. Subsequent investigations by the NAACP and federal attorneys coupled with a parent’s complaint led the U.S. Justice Department to file suit against the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners on May 31, 1968, for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment as interpreted by (see ). IPS responded that neighborhood schools were a sound concept and that one-race schools resulted solely from residential patterns, not from intentional policies.

To assuage its critics, IPS ordered limited teacher reassignments to relieve segregated patterns. Several teachers attempted to block the order, and a local resident’s organization, Citizens for Quality Schools, fought the suit to protect their neighborhood schools.

1971-1992

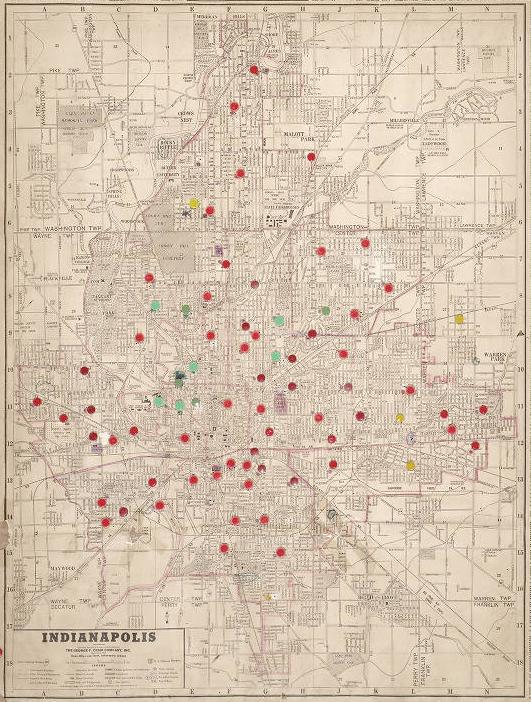

On August 18, 1971, U.S. District Court found that Indianapolis schools had not desegregated after the 1949 state law or the 1954 decision and had continued to operate a de jure segregated school system. Local officials, he concluded, had actively promoted segregation through the drawing of school districts (90 percent of 360 boundary changes since 1954 supported racial segregation), creation of new “feeder” schools, and placement of low rent housing.

The court enjoined IPS to reassign staff and faculty, revise transfer policies, and negotiate with suburban school corporations for the transfer of minority students. Concluding that had fostered segregation by expanding the city limits to encompass the predominantly white surrounding townships and excluding the increasingly Black Indianapolis school district from that expansion, Dillin sought to include the outlying school corporations in the court’s proposed solution.

The issue of desegregation dragged through the federal courts for several more years. Attorneys for Black students argued for the adoption of an inter-district or unified school plan. While the state of Indiana denied responsibility for perpetuating segregation in Indianapolis schools, Judge Dillin ruled that the state possessed control over local school districts and had approved three new high schools at the outer limits of IPS, all without African American students.

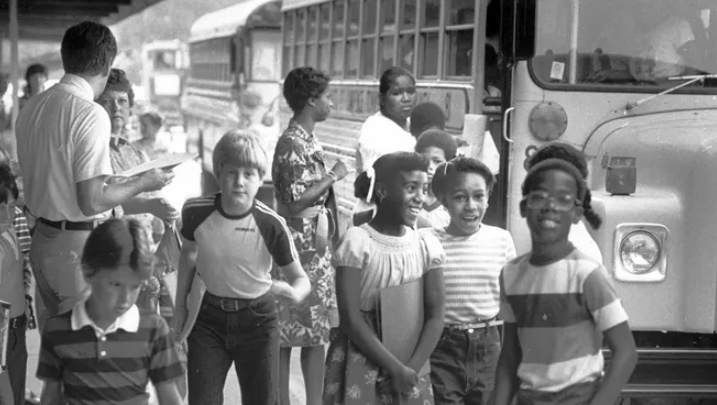

Concluding that a lasting remedy should include suburban school districts both in and outside Marion County, Dillin ordered the one-way busing of Black IPS students to 19 other school districts in Marion and six neighboring counties, with IPS absorbing the expenses. While Dillin’s cross-county busing order was reversed on appeal, his order to bus students to suburban school districts in Marion County was affirmed.

In 1981, 10 years after Dillin’s decision, the busing of 5,600 African American students to white schools in , , , , Lawrence Township, and began. Although 19,000 students were bused within the IPS district under the desegregation order, no township students were bused to IPS schools to ensure racial balance.

Most of Marion County felt the impact of the court-ordered desegregation plan. Parents of township school children who opposed the busing order began a campaign to oust Judge Dillin. Others formed the Community Desegregation Advisory Council, a volunteer group to arbitrate complaints and monitor the progress of desegregation; it ceased operations in fall, 1991. Whites continued to display unease about court-ordered busing and moved to predominantly white suburbs, even though many more city neighborhoods were being integrated.

As a result, IPS encountered plummeting enrollment (from 108,000 in 1971 to 47,000 in 1993, to fewer than 30,000 in 2016) and a deteriorating infrastructure. Many African Americans who lamented the loss of neighborhood schools also resented implications that their children learned best in white schools and that their children were singled out for one-way busing.

Over time, shifting demographics called the original court order into question and seemed to affirm the court’s position that only a metropolitan-wide desegregation plan would work and prevent re-segregation.

1993-Present

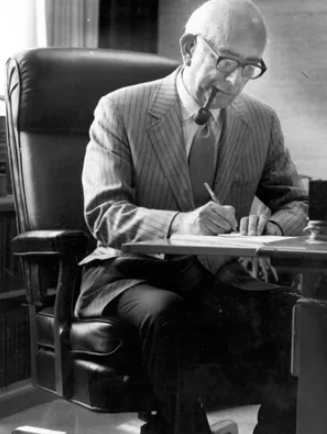

Amidst increased pressure to end forced busing, in 1992 IPS superintendent Shirl Gilbert II, argued that the “desegregation plan has simply eroded,” and requested the district court to review its desegregation order and to accept a proposed “Select Schools” plan. In February 1993, Judge Dillin, acknowledging the partial failure of the original desegregation order, allowed IPS to begin implementing a limited school choice program termed Select Schools in fall 1993.

The busing order, however, remained in place until 1998 when an agreement was reached to phase out busing over the next 18 years. Busing ended altogether, as scheduled, in 2016.

The long battle to desegregate Indianapolis schools led to a multi-ethnic, multi-racial IPS but not one that its proponents had long envisioned. White flight to the suburbs and the growth of a significant Hispanic/Latino population resulted in an IPS student population by 2020, as over 75 percent Black, Hispanic/Latino, and multi-ethnic.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.