Jewish faith and tradition have developed and adapted to changing circumstances over its long history. Although Jewish religion is not monolithic, it includes belief in one God, the centrality of Torah, and the unity of the people. Jews have interpreted these ideas in a variety of ways. Judaism is at heart a communal religion.

Wherever Jews settled in the United States in sufficient numbers, they formed Jewish organizations, usually beginning with a burial society, a synagogue, then benevolent and charitable associations, Hebrew and Religious schools, and other volunteer associations. While the synagogue is the focus of religious life, Jews have expressed their associational, philanthropic, educational, and social justice values through diverse organizations. Jews who settled in Indianapolis followed this pattern.

Seven years after the arrival of the first three Jewish residents—Alexander and Sarah Franco and Moses Woolf—to the city, a group of 14 men founded the city’s first synagogue, the , on November 2, 1856. Within two years the congregation had purchased land for a cemetery, rented rooms, hired S. Berman to act as cantor, sexton, and ritual slaughterer (to provide kosher meat), and ordered prayer books, a Torah scroll, and other religious artifacts. The congregation modified Orthodox Jewish practices fairly quickly and was an early adherent of Reform Judaism.

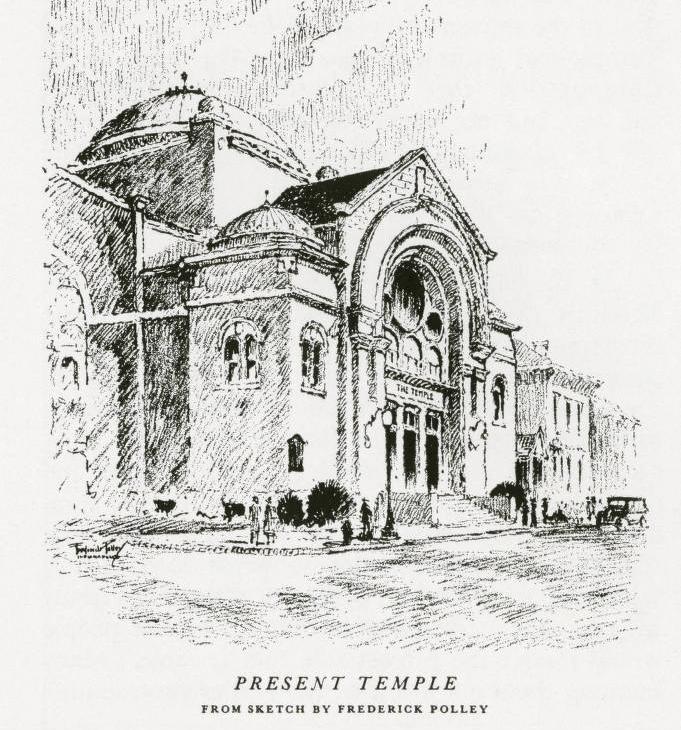

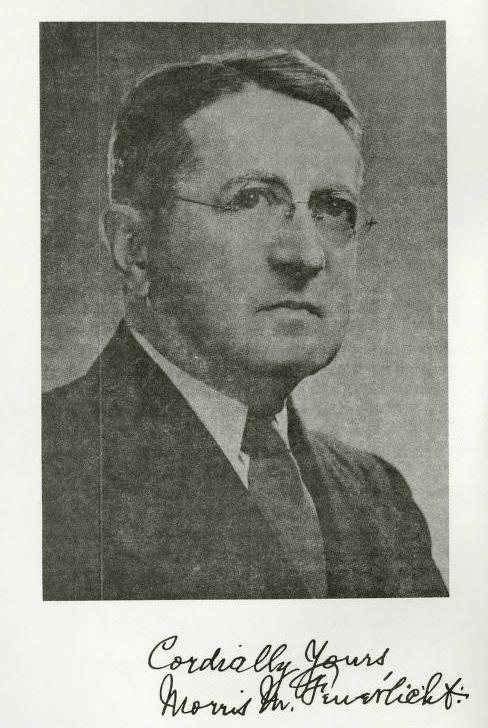

The Jewish community in Indianapolis grew and prospered, so did the synagogue. Most of the city’s Jews were in the clothing trade—about 70 percent of the clothing businesses in Indianapolis were Jewish-owned—and the brought increased orders for uniforms. The congregation dedicated its first building, located on East Market Street, in 1868. The congregation’s rabbi, Mayer Messing (1845-1930), remained with the synagogue for 40 years and was active in the city’s charitable and civic life, as was his assistant and then successor, (1879-1959). Other Jewish organizations established during the 1860s and early 1870s included charitable groups such as the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society (1859), men’s social clubs, of which only B’nai B’rith Abraham Lodge No. 58 (founded 1864) survives, and mutual benefit societies such as the Tree of Life Mutual Benefit Association (founded 1870).

Eastern European immigration substantially increased the size of the Indianapolis . In 1870 around 500 Jews lived in the city. By 1894, the estimated that there were 2,125 synagogue members in the capital. The local Industrial Removal Office estimated the number at between 6,000 and 7,000 in 1910. The Jewish population has generally remained at 1 percent of the city’s population, except for the period immediately following World War I, when it rose to 2.5 percent. In the early 1990s, the Jewish Federation of Greater Indianapolis estimated the population at 11,000.

Impoverished Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe brought diversity and change to an increasingly middle-class and Americanized community. These newcomers settled on the southside where they created a series of synagogues, each founded by Jews from a particular part of Europe. Sharah Tefilla, originally known as Chevro Bene Jacob, came first, founded by Polish Jews about 1870. The Hungarian Hebrew Ohev Zedeck Congregation followed in 1884. In 1899, Ohev Zedeck purchased the vacated building of the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation on East Market Street. The congregation, following its members, had moved north to 10th and Delaware streets; it moved farther north in 1958.

Immigrants from Russia established the third Orthodox immigrant synagogue, Knesses Israel, in 1889. Although the founders of the United Hebrew Congregation (1903) were all Galician immigrants, they wanted to overcome the divisiveness of “old country” attachments and establish a “modern” Orthodox synagogue. Ezras Achim, founded in 1910 and known as the peddlers’ synagogue, was the last of the eastern European immigrant synagogues.

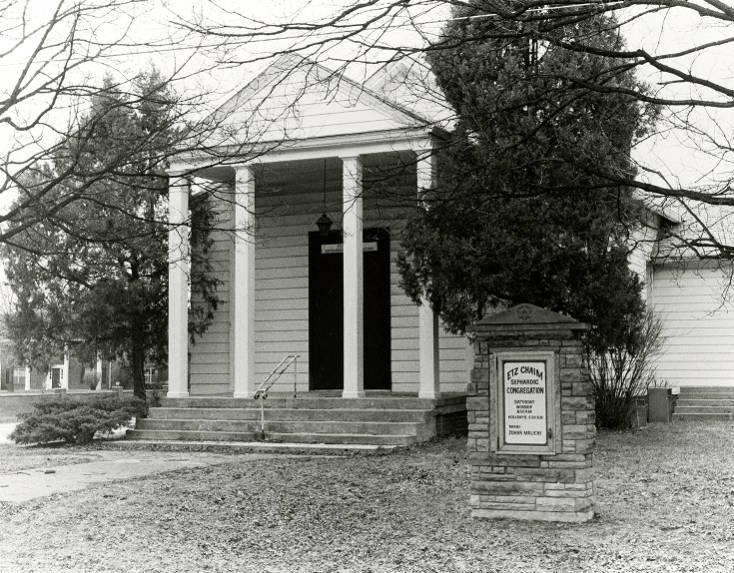

Jews from Monastir, then a part of Turkish Macedonia, began settling in Indianapolis in 1906. Sephardic Jews, primarily from Turkey, Greece, and Syria, formed a small proportion of the Jewish immigration to America. (Sephardic Jews were descendants of those who had been expelled from Spain by the Inquisition in 1492). Their language and customs had been influenced by the Spanish and Middle Eastern cultures in which they had lived, and thus the eastern European majority perceived them as “different.” Indianapolis was one of a handful of American cities with a Sephardic Jewish community. The original group from Monastir attracted more newcomers and in 1913 they founded Congregation Sepharad of Monastir. The name was changed to Etz Chaim Congregation in 1919.

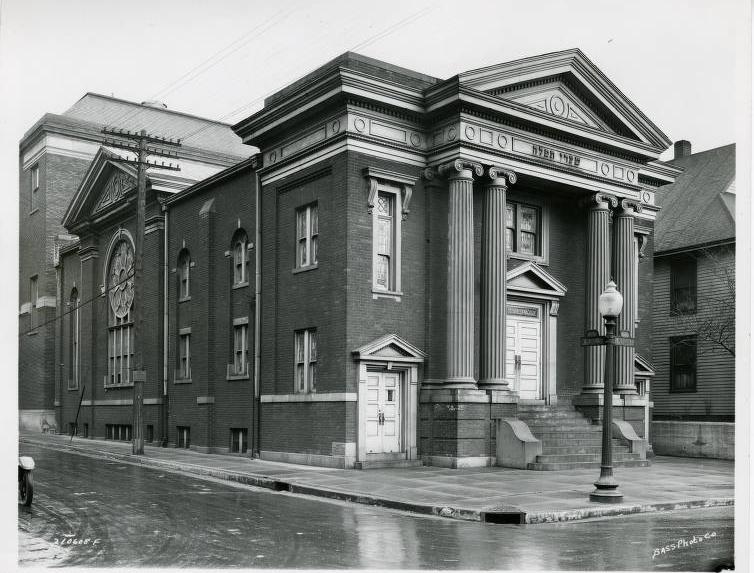

As early as 1915, a group of former southsiders and leaders of Sharah Tefilla had established a synagogue, Congregation Beth-El, on the northside. Beth-El merged with the Hungarian Congregation Ohev Zedeck in March 1928 and became . Under the guidance of a progressive young rabbi, , it became a liberally oriented Conservative congregation. In 1955, congregation Beth-El Zedeck affiliated with the Reconstructionist movement while retaining its affiliation with Conservative Judaism. A roster of prominent rabbis including William Greenfeld (1946-1960) and Sidney Steiman (1960-1974) served the congregation. In 1958 the synagogue moved from its historic landmark building at 34th and Ruckle Streets to its new facilities on the far northside.

A Jewish community requires more than synagogues to sustain it. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, Indianapolis Jews established a wide range of organizations, including benevolent societies, charities, and Zionist associations. United Hebrew Schools, a community-supported afternoon Hebrew school, began in 1911. It became the Jewish Educational Association and an affiliate of the Jewish Federation in 1924 (since 1980, the Bureau of Jewish Education). The Jewish Federation, founded in 1905, established a unified method of fund-raising and distribution of funds to support local and national Jewish organizations. The Federation provided direct relief to poor Jews, established relief-giving agencies such as the Communal Building, a southside settlement house previously known as the Nathan Morris House, and made allocations to both national organizations and local groups. It became the Jewish Welfare Federation in 1948 and, more recently, the .

After 1924 and the imposition of strict national immigration quotas, the growth of the Indianapolis Jewish community slowed considerably. The existing community prospered, however, and Jews began moving out of the southside. Some of these former southsiders founded Central Hebrew Congregation in 1923. Other than that, synagogue development, starting in the 1920s, primarily involved relocations and mergers rather than new congregations. As the community became increasingly native-born, the importance of national origins and allegiances declined.

Central Hebrew Congregation and United Hebrew Congregation, still located on the southside, merged in 1957 to become the largest Orthodox Jewish congregation in Indiana. (It eventually became the Shaarey Tefila Congregation and moved to Carmel in 1992). A year later, the congregation, renamed Congregation B’nai Torah, moved to its present location on the city’s far northside.

Sharah Tefilla, Knesses Israel, and Ezras Achim merged to become United Orthodox Hebrew Congregation and left the southside in 1966. Membership in United Orthodox Hebrew Congregation preserves a link to the past and the old southside community. Many of the members also belong to one of the three major synagogues: Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation (Reform), Beth-El Zedeck (Conservative-Reconstructionist), or B’nai Torah (Orthodox). Etz Chaim Congregation, the synagogue of the Sephardic Jews, moved to the far northside in 1963.

Membership in Etz Chaim is seen as a way for the members to preserve their Sephardic heritage and identity, although many also belong to one of the major synagogues. Beth Shalom Congregation, a new Reform Congregation was founded in Carmel in 2010.

Indianapolis Judaism reflects the contradictory trends of American Jewry as a whole. The Hebrew Academy of Indianapolis, a Jewish day school that opened in 1971, spoke to the desire of many Jews to strengthen Jewish identity and Jewish education through private education.

Conversely, the number of Jews who marry non-Jews has increased from 10 percent in the 1960s to nearly one-third and more today. Congregations are sensitive to outreach to religiously blended couples and welcome converts to Judaism. Jewish activities in Indianapolis also center on support for humanitarian needs in Israel and, in recent years, the resettlement of Soviet Jews.

Between 1989 and 1991, over 200 Soviet Jews settled in Indianapolis. Social justice activism on behalf on behalf of local and universal causes (immigration, homelessness, hunger, health care, education, race relations, etc.) are at the heart of the agenda of the organized Jewish community.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.