Photo info ...

Credit: Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Indiana Historical SocietyView Source

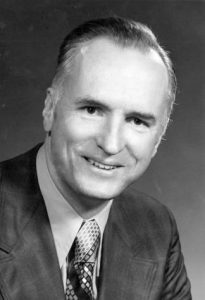

(Oct. 17, 1932–Dec. 18, 2016). William H. Hudnut III was not only the longest-serving mayor but also one of the city’s most beloved. Forever linked to the sports strategy that helped bring the Baltimore to Indianapolis in 1984, Hudnut’s terms as mayor saw the maturation of public-private partnerships that helped to transform the shape of downtown.

Hudnut’s path to politics was unique: he arrived in Indianapolis in 1964 to serve as minister for the . Like his father and grandfather before him, Hudnut had attended Princeton University (from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa) and Union Theological Seminary. At the latter, he worked with noted theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, whose teachings helped Hudnut once he entered political life.

He first did so in 1972, when he was elected to represent the 11th Congressional District in the House of Representatives. Just two years later, his fortunes reversed when he lost his re-election bid, and Hudnut’s political career seemed over. Instead, he soon received the nomination for mayor in 1975, following . Both men were protégés of and representatives of the young, intelligent candidates that Bulen recruited to reshape Republican politics in the city.

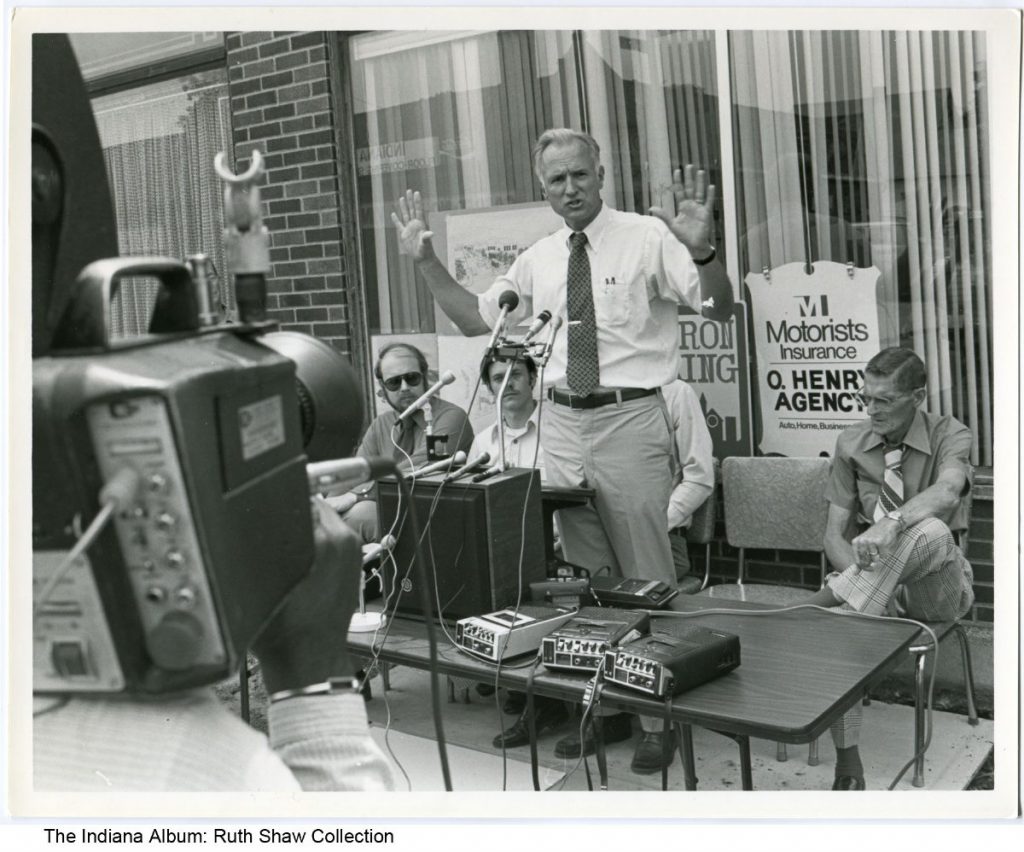

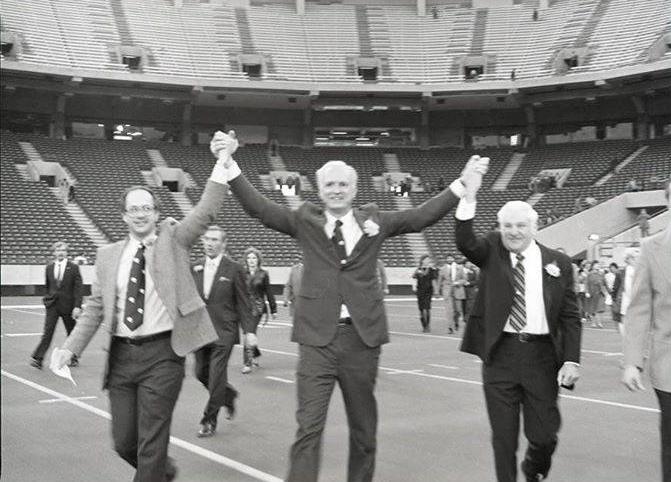

Seldom has the personality of a mayor better matched his moment; Hudnut took pride in being the consummate cheerleader for Indianapolis’s economic development. Using the sports strategy as the primary lever, Hudnut, along with the , continued a close working relationship with private philanthropy, most notably the In addition to the bold gamble of erecting the with no major sports tenant at the time, the Indianapolis community staged a number of sports festivals throughout the 1980s, most notably the 1987 . This proved to be the city’s moment on the national scene.

But Hudnut also showed personal leadership. When the shuttered Indianapolis for three days, Hudnut demonstrated that charismatic leadership can help residents connect with city services. He was omnipresent during the emergency, appearing frequently on television and reassuring citizens that the city was doing all that it could do to make the situation better. Many residents fondly recall the blizzard as Hudnut’s finest hour.

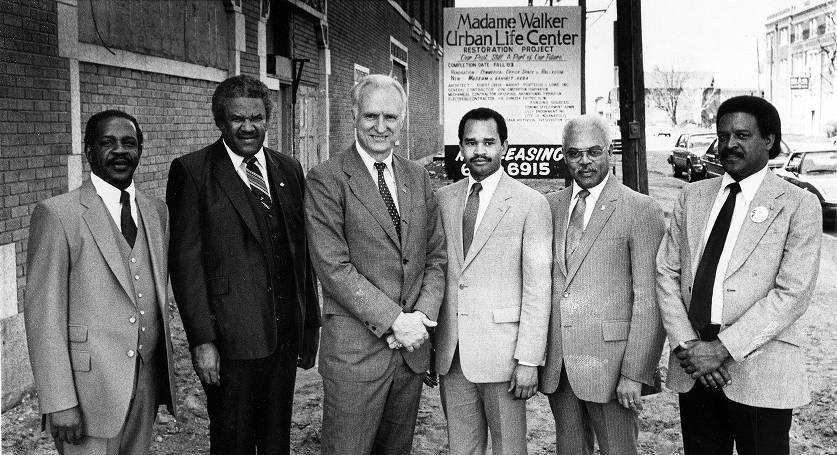

Hudnut was a firm advocate of affirmative action hiring. He took the Ronald Reagan administration to court in order to proceed with the city’s plan to diversify its police and fire departments. Although Hudnut sought to improve the city’s racial climate, he acknowledged that those were always the toughest issues that he faced as mayor.

None was more challenging than the shooting death of 16-year-old Michael Taylor, who in 1987 was found dead in the back of an Indianapolis police car from what investigators labeled a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The ensuing unrest that ensued from the fractured many of the relationships that Hudnut had established in the African American community.

Hudnut’s popularity in office was legendary. An engaging public figure, Hudnut used all of his 6’6” frame to endear himself to citizens. Whether it was his campaign to curb litter with an iconic “Hudnut Hook” commercial or his countless public appearances, Hudnut courted goodwill. In a sign of his popularity, in 1984 the Indiana Legislature amended its laws, allowing Hudnut to serve more than two consecutive terms. This legislation became widely known as the “Hudnut Forever” bill.

With an eye toward higher office, in 1990, Hudnut campaigned to become Indiana’s Secretary of State. Attacked for having raised a variety of taxes during his years as mayor, Hudnut suffered a stunning upset, losing to Democrat and future Indianapolis Mayor Joseph Hogsett. Soon thereafter, he announced that he would not seek reelection to a fifth term in 1991.

Hudnut’s transition to private life was initially rocky, fueled in part by a variety of personal scandals that had received attention during his last years in office, as well as the icy relationship that had developed between him and Marion County Prosecutor Stephen Goldsmith, who succeeded Hudnut as mayor. In style and temperament, the two were different enough that a significant rivalry developed. In subsequent years, they achieved a rapprochement, but it soon became clear that Hudnut might have to move from the city with which he was so closely linked.

Ultimately, Hudnut settled in Chevy Chase, Maryland, where he held a variety of positions, including mayor in 2004. He also held the Joseph C. Canizaro Chair for Public Policy for the Urban Land Institute in Washington, D.C. from 1996 to 2010.

Hudnut received wide recognition for his career in public service. He was president of the National League of Cities and a member of its board for over twenty years. In 1986 he received a Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service, and in 1988 Hudnut was named City & State magazine’s Nation’s Most Valuable Public Official. He wrote five books on his life in religion and politics, including his tenure as mayor.

In his last years, Indianapolis residents grew nostalgic for their old mayor. In November 2014, Republican Mayor Greg Ballard dedicated a greenspace directly across from the as Hudnut Commons. There, a larger-than-life statue of former “Mayor Bill” greets passersby. Hudnut hoped that people would say that “he built well and he cared about people.” Both for his enthusiasm and his ability to lead, Hudnut will be recalled as one of the most significant mayors in Indianapolis history.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.