Photo info …

Credit: Jose Mora, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsView Source

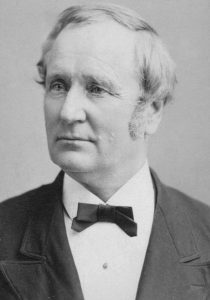

(Sept. 7, 1819-Nov 25, 1885). Thomas Hendricks was born in Muskingum County, Ohio, and moved with his family to Indiana in 1820. After schooling in and graduating from Hanover College, Hendricks read law and opened a legal practice in Shelbyville.

His father, uncle, and cousins served in the Indiana General Assembly before him. Hendricks, therefore, slid easily into politics and in 1848 won election to the Indiana House of Representatives, representing Shelby County for one term and beginning a life-long career in politics. Although he declined to stand for reelection, he served in the state constitutional convention of 1850-1851. He ran for and won two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1851-1855), serving as chairman of two minor House committees. He was defeated for reelection in 1854. However, President Franklin Pierce softened the blow by appointing him commissioner of the federal General Land Office, where he continued under President James Buchanan until 1859.

In 1860, Hendricks moved his family to Indianapolis, where he practiced law with fellow Democrat Oscar Hord. Later, the two joined with Republican Conrad Baker to form the Baker, Hord, and Hendricks partnership. The firm continued for years under the name Baker and Daniels. For many years Hendricks was one of the city’s leading attorneys. In 1860, Hendricks received the Democratic nomination to run for governor. He was defeated by Henry S. Lane, who served as governor for just two days before being selected by Republicans in the General Assembly to go to the U.S. Senate. Lieutenant Governor became governor.

The start of the (1861-1865) saw Hendricks as one of Indiana’s leading Democrats: a talented speaker, a sharp legal mind, and great ambition. However, the state party was under the firm control of U.S. Senator Jesse D. Bright, and rising Democrats had to toe Bright’s line and wait their turn. Bright’s political fortunes took a tumble when letters surfaced that he had corresponded with the leader of the rebel government, Jefferson Davis. Bright was expelled from the Senate in February 1862. The logjam at the top of the party in Indiana was effectively broken.

In January 1862, amid the Senate deliberations on Bright’s expulsion, Hendricks presided over the state Democratic convention held in Indianapolis and gave the keynote speech. While a war to suppress a rebellion by southern states bent on the preservation of slavery raged, Hendricks gave a speech calling for Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois, its neighboring states of the Old Northwest, to leave the war and the Union and create a new “Northwest Confederacy.” The new nation would find its natural allies in the rebel states of the South, where the region’s agricultural products were consumed. The Northwest Confederacy would have no problem with southern slavery.

During the same disunion speech, he threw red meat to the party faithful, repeating standard racist (and Democratic) arguments of the day: that if Republicans had their way freed formerly enslaved Black people would flood north to take away the jobs of Indiana’s white workers; that African Americans lacked “high intellectual and moral qualities,” and more.

Hendricks’ speech was a huge success and modeled Democratic talking points echoed in Indiana and surrounding states for the coming months and years. The speech burnished his credentials among rank-and-file members of the party. A reenergized Democracy won majorities in the Indiana General Assembly in the fall 1862 elections. When legislators gathered at the State House in early 1863, Democrats selected Hendricks to serve a six-year term in the U.S. Senate, rejecting a Jesse Bright comeback.

In the Senate in Washington, D.C., Hendricks continued to mouth racist fare while serving in the Democratic minority. He and other Democrats attempted to obstruct the war measures of President Abraham Lincoln’s administration. He opposed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the arming of black men to serve as soldiers and sailors to put down the slaveholders’ rebellion. He voted against the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution, which ended slavery, established equality under the law for all, and granted voting rights to African Americans. Only one other U.S. senator voted against all three measures.

In speeches on the floor of the Senate in support of his amendment votes, he argued that Blacks were not worthy of citizenship. As Republicans held majorities in the Indiana General Assembly, Republican legislators voted for one of their own to replace him in the Senate.

In 1869, Hendricks returned to Indianapolis and his law practice. In 1871, he represented Civil War conspirator Lambdin P. Milligan in a civil suit argued in federal circuit court in Indianapolis against former Governor Oliver P. Morton and a host of military officers who had been involved in Milligan’s illegal military arrest and trial. The civil trial received national attention and was one of the first civil liberties lawsuits in US history (see ). While Hendricks technically won the suit, the court granted plaintiff Milligan just five dollars in damages, a judgment on Milligan’s complicity in treason during the war.

Hendricks remained active in Democratic politics and his name was frequently put forward as the party standard-bearer. The party nominee for governor again in 1868 and 1872, Hendricks won election in 1872 and served as the state’s chief executive for four years marked by economic depression and labor turmoil.

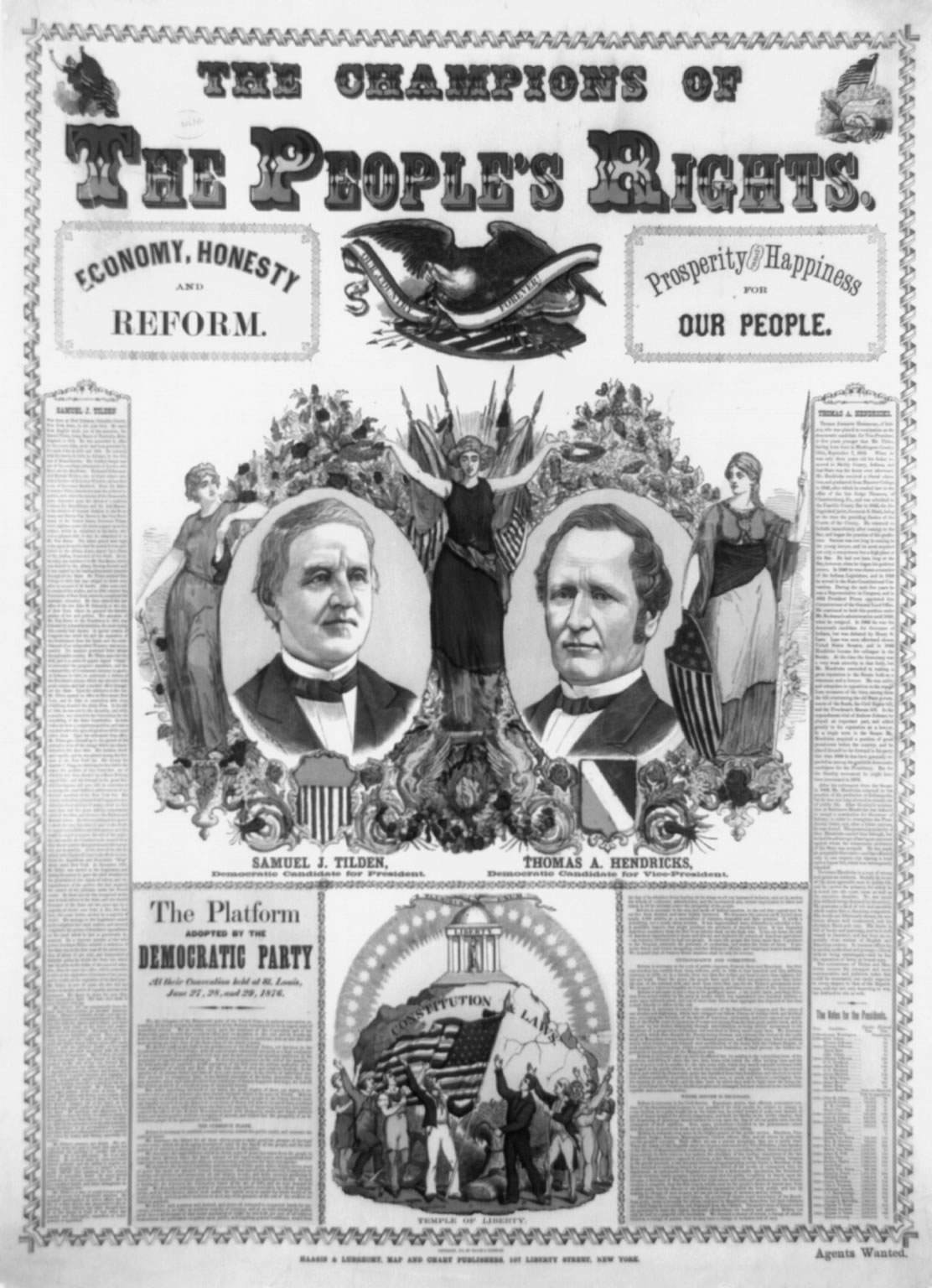

Hendricks’ importance among Democrats spread beyond state boundaries, especially as Indiana was a vital swing state in presidential elections. His name came up in party conventions to form national tickets. In 1876, he was selected to run for vice president with Samuel Tilden of New York topping the Democratic ticket. While Tilden and Hendricks won the popular vote, Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and William A. Wheeler of New York won the electoral college after a controversial, back-room deal was made.

In 1880, he turned down the nomination for the second spot on the national ticket due to poor health. In 1884, Hendricks again was the vice-presidential pick to run with Grover Cleveland. They defeated the James G. Blaine–John A. Logan Republican ticket.

Suffering ill health, in November 1885, just months into his term as vice president, Hendricks died in his Indianapolis home. Democratic newspapers in the city and state promptly called for a prominent monument to honor him for his decades of loyal party service. Their primary reason for a monument was to counter a recently erected statue in Circle Park honoring Republican hero Oliver P. Morton. In 1890, Democrats unveiled a huge statue of Hendricks outside the State House.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.