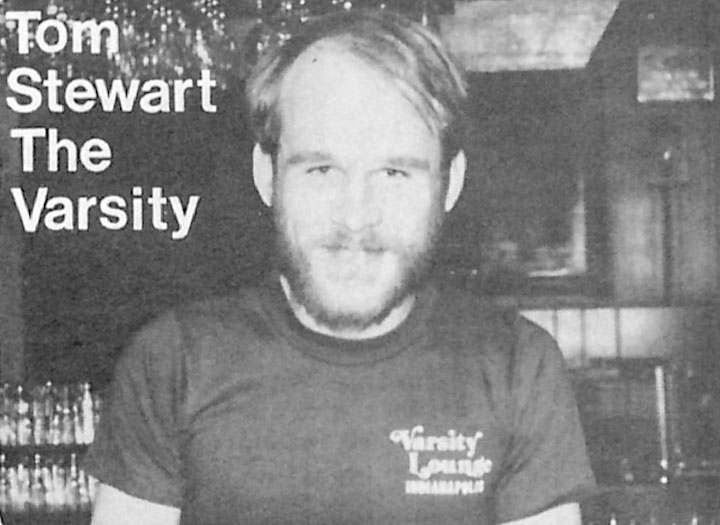

The Varsity Lounge, located in Indianapolis’s historic neighborhood, is thought to be the city’s oldest gay bar and restaurant. Otto and Emanuel Zen Dell established the business as Zen Dell’s Tavern in 1937, but by the 1950s the venue had a different owner, name, and clientele. As an early gay business in Indianapolis, the Varsity Lounge provided its patrons a place to forge community bonds, and eventually to organize politically and challenge societal norms. However, during its later decades the bar also attracted controversy for practices aimed at excluding transgender and gender-nonconforming customers.

The bar was located at 1517 N. Pennsylvania Street, in a one-story concrete-block building, for its entire 75-year history. In 1941, the Zen Dell brothers sold the business to Gilea Kelly, who changed the name to the Varsity Bar. It was a bar known for participating in Indianapolis’s annual fundraiser for polio. The unofficial “mayor” of Old Northside’s Little Broadway section, Republican precinct committeeman Mike Maroney, levied a “tax” on all businesses in his ward as their fundraiser contribution. In 1944, a local sportswriter noted the bar’s appeal as a “‘late play’ bright spot for the downtown boys who live North.”

That ambience would change in the 1950s. By 1957, the Varsity Bar had been purchased by Cecilia J. Kolodziej Colby and her husband, who renamed the venue as the Varsity Cocktail Lounge. According to local entrepreneur Paul Eckert, who would go on to open numerous gay bars in Indianapolis, Colby served a gay clientele and sought to maintain discretion for customers by prohibiting overt displays of affection or attraction on the premises. Despite this limitation, the bar provided a safe environment for closeted or semi-closeted gay men to meet during an era when men exposed as patrons of such establishments could face severe legal and social penalties. Colby owned Varsity Lounge until she transferred ownership of the bar and the liquor license to companions and business partners, Donald Bowlen and John Wharton Jr., in 1976.

During the time of Bowlen and Wharton’s ownership, the Varsity Lounge supported events for Indianapolis’s gay and straight communities. Throughout the 1980s, the bar hosted contests for the best female impersonator. In January 1982, the bar hosted the first meeting of the Hoosier Business and Professional Guild, a statewide lobbying organization. In 1983, during the (IPD) investigation into the murders of eight gay men, the Varsity Lounge collaborated with other gay bars to raise funds to solicit information related to the homicides (see ). In 1984, the Varsity Lounge catered lunch for 1,000 people at the best-attended Greater Indianapolis Gay Business Association (GIGBA) picnic to date.

Edward Ziliak Jr. and Wayne Jones owned the venue beginning in 1985 and continued Varsity’s support for community causes. For example, in 1985 they hosted an “ugliest bartender” contest to raise money to combat multiple sclerosis. A year later, Jones worked with almost 20 gay businesses from across Indiana during Gay Pride (see ) month to support initiatives that spearheaded. As part of this thrust, participating gay-owned businesses raised funds, advocated for anti-discrimination legislation, solicited support for gay and lesbian communities from local religious organizations, demanded media coverage for an ongoing string of murders of young gay Indiana men, and held conferences on HIV education. After Ziliak died in 1986, Jones operated the club alone for two years before seeking a new buyer.

Phillip K. Church purchased the venue in 1989. Shortly thereafter, the Varsity Lounge became one of twelve Indianapolis bars to enter a team in a citywide bowling league affiliated with the International Gay Bowling Association.

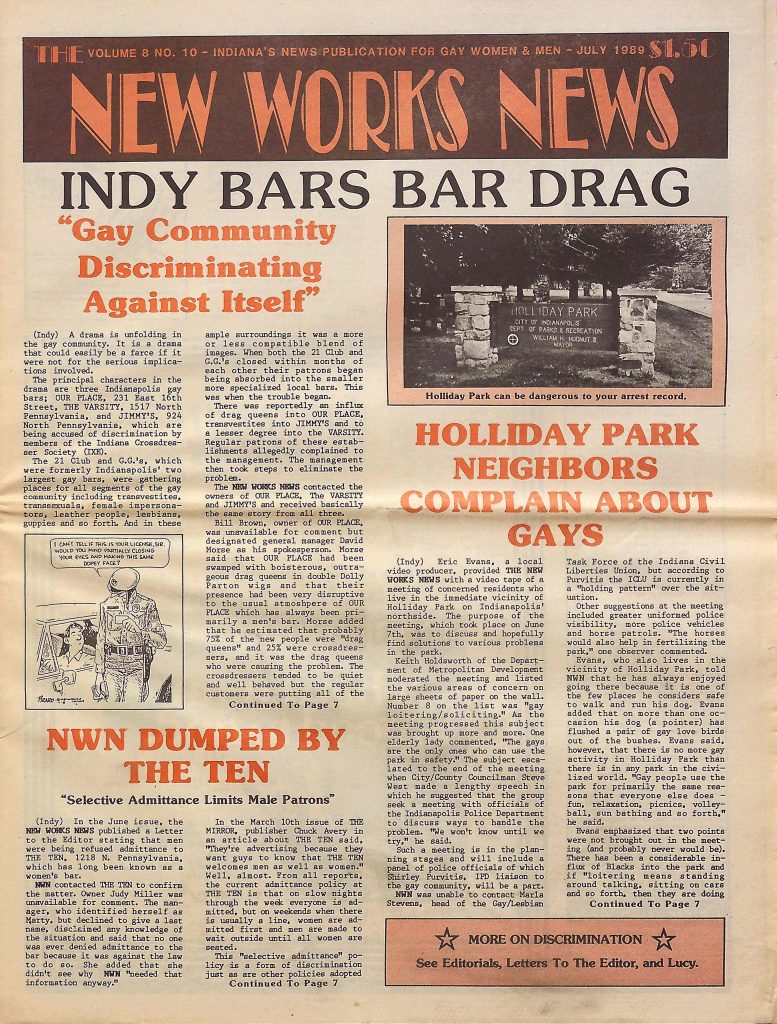

Beginning in 1989, the Varsity Lounge became embroiled in local disagreements over inclusion of transgender and gender-nonconforming customers. Along with two other gay bars— and Jimmy’s—the Varsity Lounge adopted policies aimed at shutting out such patrons. The discrimination was exacerbated by the closing of and , two gay bars that had welcomed customers with a diverse range of gender presentations. The closure of these two bars left their former patrons seeking new social hubs; meanwhile, customers at traditional gay bars such as the Varsity Lounge complained of an influx of newcomers whose dress and comportment departed from those of the established crowd. The Varsity Lounge’s new policies included strict dress codes requiring traditionally masculine attire and rules mandating that a patron’s appearance must match that shown on their official photo identification card.

In February 1989, a Varsity Lounge bartender ejected a female-presenting trans woman from the bar for not having identification matching her current appearance. The ejected patron reported the incident to the (IXE), which then informed Justice, Inc., an umbrella statewide organization with a lobbyist at the . The former two organizations, along with the , state excise officials, and the Indianapolis Police Department’s LGBTQ+ liaison, met thrice with the owners of the Varsity Lounge, Our Place, and Jimmy’s. Though the allegations of trans exclusion had prompted the meetings, participating advocacy groups reported that the conversations revealed other forms of discrimination at the three bars, aimed at nonwhite patrons, lesbians, and people living with HIV/AIDS. The talks led some bars to revise policies deemed discriminatory, but the Varsity Lounge maintained its stringent gender-normative dress code and identification rules.

In 1990, the Varsity Lounge received further visibility for its role in a community controversy over LGBTQ+ activism. That year, the New York–based AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP), a direct-action protest organization, asked LGBTQ+ consumers and allies to join a nationwide boycott of Marlboro tobacco and Miller beer products, due to support by their parent corporation, Philip Morris, for politicians such as US senator Jesse Helms and other opponents of LGBTQ+ legal protections and HIV/AIDS research funding. While some owners of LGBTQ+ bars in Indianapolis agreed in principle to participate, several others refused. The latter group included Church, who expressed concern that his Varsity Lounge might lose clientele to venues still serving Miller beer, especially given the popularity that Miller Lite had earned among gay consumers of the era. The boycott ended when ACT-UP persuaded Philip Morris to fund AIDS research, but divisions over the boycott exposed political fault lines within Indianapolis’s LGBTQ+ commercial and activist networks.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, transgender individuals gained greater acceptance within Indianapolis’s gay, lesbian, and queer institutional networks. During this era, the Varsity Lounge displayed increasing openness to gender-nonconforming patrons and entertainers, as suggested when Church allowed the bar to become a stop for a bus tour by the Indy Bag Ladies, male drag performers raising money to combat HIV/AIDS. , the city’s LGBTQ+ magazine, continued to advertise the Varsity Lounge as a bar and restaurant for men; however, the establishment did relax the dress code and identification checks that had once excluded trans and gender-nonconforming patrons.

In 2019, Church sold the Varsity Lounge property to krM Architecture for $270,000. The architectural firm converted the building into a mixed-use facility called the Varsity Lofts, with the new name referencing the site’s important role in local LGBTQ+ history.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Verderame, J. (2025). The Varsity Lounge. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 20, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/the-varsity-lounge/.

MLA:

Verderame, Jyoti A. “The Varsity Lounge.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025, https://indyencyclopedia.org/the-varsity-lounge/. Accessed 20 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Verderame, Jyoti A. “The Varsity Lounge.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025. Accessed Feb 20, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/the-varsity-lounge/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.