Alcohol long has been an accepted part of American life. By the early 19th century, many people and physicians believed that alcoholic beverages in moderation were beneficial to one’s health. Political candidates even distributed whiskey freely at polling places to win support from voters. During those same years, there were growing concerns about the misuse of alcohol and its impact on personal health and family life. Religious revivals preached the evils of “intoxicating drink” and sobered up many converts who joined “the cause.” Strong nativist feelings against German and Irish immigrants inspired local efforts to restrict the production and sales of liquor. As a result, alcoholic beverages and politics proved to be a volatile mix throughout Indianapolis’ history.

Beginning in eastern states during the early 1800s the temperance movement quickly spread nationwide. On October 3, 1828, Indianapolis residents met at the Methodist meetinghouse to organize the Temperance Society of Marion County. They pledged “to discontinue the use of ardent spirits, except as medicine” and agreed that “entire abstinence is the only course which promises success in suppressing intemperance.” In December 1829, representatives from around Indiana met in Indianapolis to organize the Indiana Temperance Society, which considered “the habitual use of ardent spirits [to be] injurious to health, destructive to the mental faculties, and tends to shorten human life.”

Even though the words temperance and prohibition were often used interchangeably, they had different meanings and produced different agendas. Temperance suggested voluntary abstinence, whereas prohibition implied legal remedies and restrictions. Temperance came first, with the American Temperance Society, the Washingtonians, and assorted fraternal organizations collecting abstinence pledges, mounting public marches, and working to develop a consensus against alcoholic beverages.

In early 1852 Indianapolis hosted a temperance revival during which nearly 900 people formed the Social Order of Temperance and “signed the pledge.” Between 1830 and 1850, groups such as these helped secure the passage of more than 125 local laws throughout Indiana that encouraged temperance by regulating prices and quantities of alcohol sold, not by enforcing abstinence.

Voluntary abstinence soon gave way to demands for prohibition. The People’s Party, a forerunner of the , won a major statewide victory in 1854 on a platform advocating temperance and opposing the extension of slavery. The General Assembly subsequently enacted a law in 1855 to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcohol, except for medicinal purposes. Local Germans and Irish opposed the law, although one Indianapolis newspaper proclaimed the law a success since it “diminished crime, reduced drunkenness, saved money and emptied jails.” But the state Supreme Court in the 1855 , which originated in Marion County, declared the law unconstitutional on grounds that it violated property rights and the guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure.

New temperance groups arose following the Civil War, including the (1874). A coalition of groups unsuccessfully promoted various restrictive laws, including one that would make saloonkeepers liable for customer injuries resulting from the use of alcoholic beverages.

The first significant temperance law enacted by the General Assembly after the war was the Baxter Act (1873), which required the approval of a majority of voters in a ward, town, or township before a liquor license could be granted. In Indianapolis, however, the Democrats won control of the city council for the first time since 1860. The attributed these Republican losses to “ill-conceived and misdirected zeal of the so-called temperance people.”

Later in 1881, the Indiana General Assembly proposed a constitutional amendment to prohibit the manufacture or sale of alcoholic beverages in the state. The amendment became linked with a women’s suffrage bill and the following year both were defeated after anti-prohibition Democrats swept the elections (See ).

An important temperance advocate was Governor , who in 1908 pushed a county local option law through the General Assembly. In response, 70 of 92 counties, by November 1909, had voted to forbid the sale of alcoholic beverages. However, it appears that Marion County remained “wet.” Following his term as governor, Hanly founded the Flying Squadron of America in Indianapolis to promote national prohibition and established the , which became a leading temperance newspaper.

Although the Democratic-controlled legislature repealed the county option measure in 1911, the General Assembly enacted a statewide prohibition law in 1917. Two years later Indiana ratified the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors.

Following the adoption of statewide prohibition, Indianapolis immediately witnessed the impact of the legislation. Police reported a 74 percent decline in arrests during the law’s first week of implementation; only 26 people were arrested over the first weekend, compared to the usual 100. “The sudden decrease in the number of brawls, shootings, and other disturbances, usually common on Saturday nights, was attributed by policemen to the fact that the city’s 500 or more saloons closed their doors last Tuesday at midnight,” reported the . The first month of the law saw a 35 percent decline in crime in the city. The county workhouse, where criminal offenders paid fines with work, was soon closed because of a lack of business.

Prohibition was never strictly a party issue. But given the socioeconomic characteristics of political parties, Republicans tended to favor prohibition and strict regulation, whereas most Democrats favored less or no regulation. In both state and city politics, a candidate’s stance on temperance could truly make the difference on election day.

About this time, Methodist minister Edward S. Shumaker came to Indianapolis to head the Indiana Anti-Saloon League. Formerly superintendent of the league’s South Bend district, Shumaker secured the passage in 1925 of a “bone dry law” that strengthened prohibition enforcement. Found guilty of contempt for criticizing the Indiana Supreme Court’s prohibition law decisions, Shumaker served a 60-day sentence at the State Farm in 1929. Considered a hero for the cause, he died a few months following his release.

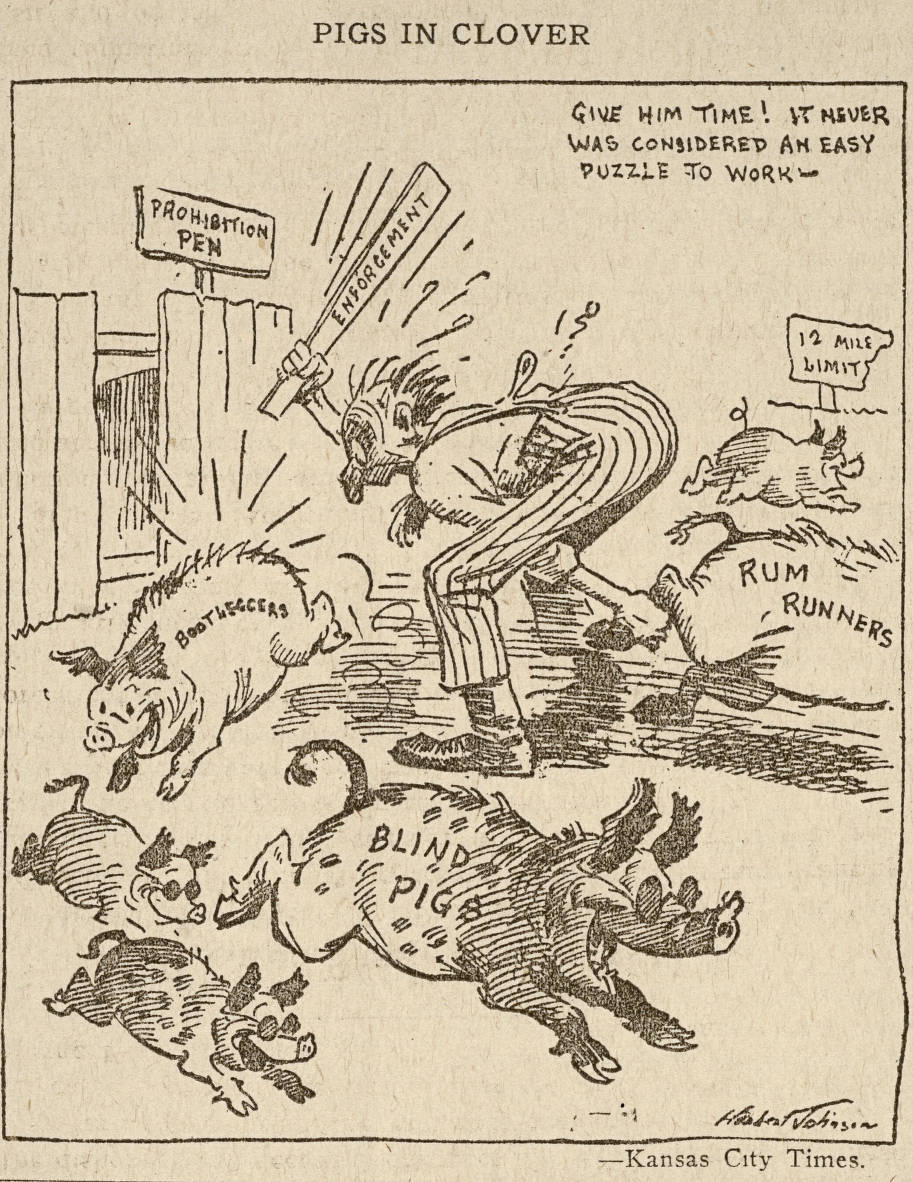

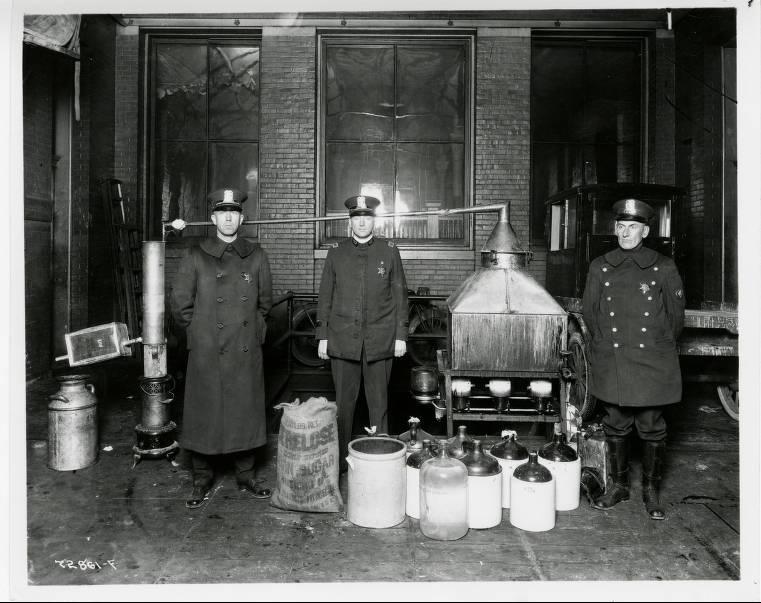

Prohibition reduced some crime, but law enforcement officials could not keep up with illegal efforts to make and sell alcoholic beverages. The proposed repeal of prohibition just before the Great Depression began in 1929 failed, but by the 1932 election, the voters were ready to end the experiment. State and national prohibition laws were repealed soon thereafter.

Following the legislature’s repeal of the “bone dry law” in 1933, Governor Paul McNutt and the Democratic Party established regulations over the newly legal business through the Alcoholic Beverage Commission. Liquor and politics continued to mix, this time through the use of liquor licenses as political patronage. When the Republicans took over state government after World War II, they likewise used liquor regulation to distribute political rewards. In Indianapolis, the county government regulation of the industry also provided political patronage, controversy, and scandal.

Indiana continued to have some of the most restrictive laws pertaining to alcohol in the U. S., but those laws loosened slowly over time. In 1953, Indiana package liquor stores began to sell beer. Hotels, restaurants, bars, and private clubs were permitted to sell alcoholic beverages on Sundays beginning in 1973.

By the 1980s, there was a growing awareness of the social impact of drinking. In 1981, the nation recorded 25,000 fatalities attributed to drunken drivers, including 282 deaths in Indiana. Marion County Prosecutor Stephen Goldsmith launched a statewide crusade against the crime as head of the Governor’s Task Force on Drunk Driving. Local chapters of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD) were organized in 1982. The Indiana General Assembly adopted stricter laws in 1983 to reduce the deaths attributed to this crime. Public health advocates issued warnings about the dangers of alcoholic beverages, especially for babies in mothers’ wombs. Elected in 1988, Governor Evan Bayh promptly banned the use of hard liquor at public events in the Governor’s Residence and later added beer and wine to the ban.

In 2010, the prohibition against selling alcohol while election polls were open came to an end, although that law did not come into practice until 2012. Governor Eric Holcomb, in early January 2018, signed into law Senate Bill 1, which repealed the Prohibition-era law that banned Sunday sales of alcohol at liquor, grocery, drug, and convenience stores. The law legalized sales on Sunday between noon and 8 pm. The first day that Sunday carryout alcohol sales were allowed drew large crowds. Efforts to expand the hours for alcohol sales have failed, and the happy hour at bars and restaurants remains illegal. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, Governor Holcomb, however, kept liquor stores open in his “stay-at-home” executive order in March of that year.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.