Mayor established the Tanselle-Adams Commission on November 26, 1980, to investigate police practices involving the use of deadly force and to develop recommendations to improve relations between police and the community. He called for its creation following protests against the death of Michael N. Smith, a 15-year-old Broad Ripple High School student who was shot by an officer. The incident occurred after an armed robbery at a liquor store on East 46th Street that took place on November 4, 1980. The police officer saw Smith, who appeared to match a description of the suspect involved in the robbery, walking at Keystone Avenue and Millersville Road. When the officer ordered Smith to stop, he fled. The officer fired twice at Smith, who was struck once in the upper back and died from the wound.

The commission consisted of 25 members from the Indianapolis community including political and religious leaders, local business owners, and representatives from community groups. The mayor’s office did not directly appoint any members to the commission. Hudnut invited 23 community groups to participate in the organization of the commission, and they selected its members. Hudnut followed their recommendations and appointed William Roberts, an attorney, and Lehman Adams Jr., a dentist and civic leader, as vice chairman. Roberts, however, resigned from the commission in early December 1980 to avoid “any possibility of a conflict of interest.” His law firm Roberts Ryder Rogers & Neighbours represented the Indianapolis Police Department and the Marion County Sheriff’s Department in labor law matters. Hudnut replaced Roberts with Donald Tanselle, who was president of the .

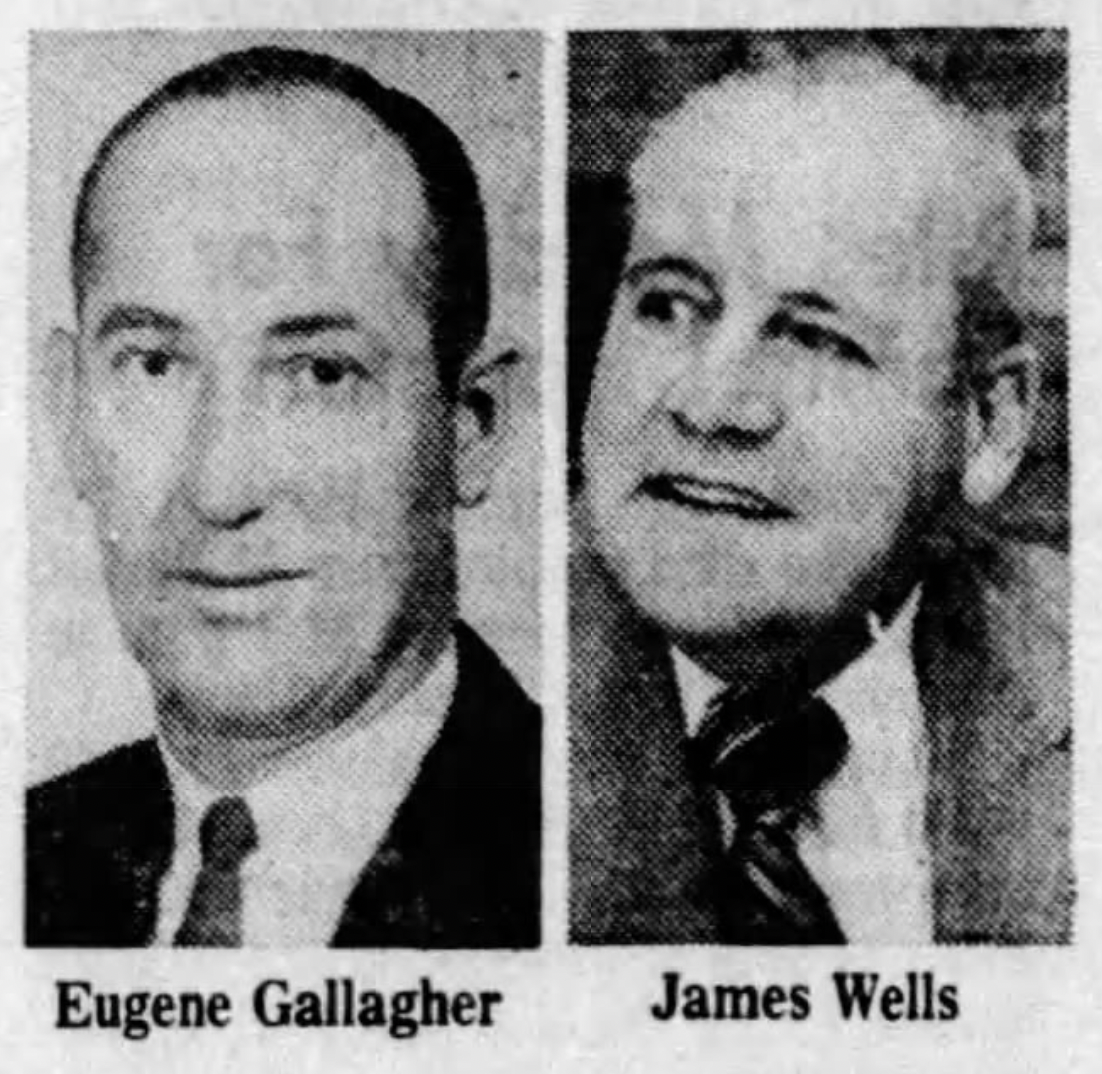

On December 5, 1980, Hudnut told the that the purpose of the Tanselle-Adams Commission was not to investigate one specific incident or the Indianapolis Police Department but instead to “inquire into the adequacy or inadequacy of the law” as it related to use of force by law enforcement. For its investigation, the commission took testimony from law enforcement personnel and members of the Indianapolis community. Police Chief Eugene Gallagher and Sheriff James Wells both testified in favor of the law and regulations governing use of force as they were established. Gallagher noted that “it is extremely difficult to make a policy which is going to fit every situation. Police officers have a certain amount of discretion and they must make good decisions.”

In early 1981, the commission held six public meetings to receive comments from the public and one meeting dedicated to comments from law enforcement. During the public meetings, some residents expressed support for the existing use-of-force policy—not wanting to “handcuff” the police. Others criticized the Indianapolis Police Department policy that allowed officers to shoot at fleeing suspects. Some community members criticized how the commission itself had been constructed. Reverend , for example, questioned why only one minister had been appointed among the commission’s 25 members. Twenty-five members of the Indianapolis Police and departments testified unanimously against any changes during the law enforcement meeting. They argued that, if the policy was changed, criminals would benefit, and the community would be at risk. Some of them openly blamed the courts for crime rates, and one officer remonstrated, “I don’t condone or recognize your so-called Commission.”

Representatives of the FBI and the Indiana State Police also gave testimony. They argued that deadly force should be authorized if a trooper or agent has a reasonable belief of injury or harm. The state police also reported that they would open fire on a fleeing felon, if necessary, to effectuate an arrest. A representative of the National Black Police Association provided a statement in opposition to such use of force. He declared that shooting a fleeing suspect was “absolutely a criminal act.”

In May 1981, the Tanselle-Adams Commission announced its recommendations. The commission found that the issues involved went beyond analyzing use of force and relevant statutes and ordinances. The commission instead stated that the chief issue related to the lack of communication and coordination between law enforcement and the general community.

To address these problems, the commission recommended investment and commitment to improve police training, counseling, police community relations, and citizen complaint procedures. The commission identified the need for a civilian committee to improve relations between citizens and law enforcement. It called for cultural sensitivity and psychological training for members of the police department and counseling for officers involved in a police action shooting and for their families. It also recommended counseling for victims of violent crimes. The commission analyzed statutory provisions regarding use of force and recommended amendments to Indiana statutes during the next session of the Indiana General Assembly that would allow charging fleeing suspects with a C-level felony. It also recommended a change that would allow police to use lethal force if a suspect were involved in a forcible felony, including murder, rape, residential burglary, robbery, kidnapping, assault, and aggravated robbery.

On May 14, the commission voted to adopt its recommendations with a 15-4 vote. Commission member and State Representative detailed his “nay” vote in a separate written explanation. He noted that his vote was not against the recommendations. He instead criticized the commission for allowing for the submission of a supplemental report, dubbed the “Dowden Report” for Republican city-county councilor William Dowden who argued against the need for a civilian policy community relations committee. The commission’s supplemental report alleged that no evidence had been presented during the investigation to support any racial motivation in the use of force by city law enforcement. The Dowden report also did not recognize any disproportionate use of force against minorities. Crawford questioned the information used in that report and explained that he was concerned that this viewpoint might be viewed as the position of the Tanselle-Adams Commission.

Mayor Hudnut forwarded the Commission’s final report to Indiana governor Robert Orr, as well as the leadership in the Indiana General Assembly, the president of the Indianapolis , the Marion County Sheriff, the chief of the Indianapolis Police Department, and the Indianapolis director for public safety. Hudnut asked city officials to implement the commission recommendations that fell under its purview, and he expressed hope that the state legislature would act or, at least, hold hearings on the report’s proposals.

The Tanselle-Adams Commission ended formally on March 24, 1982, to allow for the creation of a committee to work towards better relations between law enforcement and the community. Its formation, however, was delayed while the Indianapolis Police Department developed community relations programs. In March 1983, Hudnut established the Police Community Relations Review Committee as the major result of the commission’s work.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.