Laws governing the observance of the Sabbath have existed in Indiana since 1807 when territorial governor William Henry Harrison approved “An Act for the Prevention of Vice and Immorality.” When the first state legislature met in 1816-1817, it addressed Sunday observance as part of “An Act to Prevent Certain Immoral Practices,” which levied fines for anyone over age 14 found “rioting, hunting, fishing, quarreling, [or] at common labor” on Sunday. Thus, state laws initially governed local community behavior.

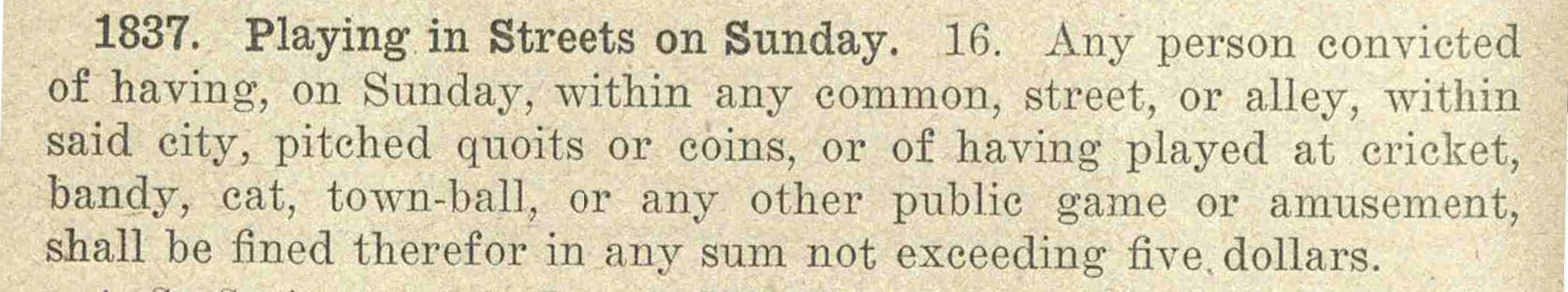

In 1837, however, Indianapolis town trustees adopted the first local ordinance regarding Sunday activities, imposing a maximum $5 fine for anyone convicted of playing cricket, bandy, or corner ball, pitching quoits or coins, or pursuing any other public game or amusement on Sunday. This law continued in existence until being revised in the early 20th century.

Whether the local law was enforced over the years is questionable. Attorney never mentioned any prosecution or conviction of Sabbath breakers in his diaries. Reverend , pastor of , often alluded to the lax attitude of westerners about keeping the Sabbath holy.

In an effort to prevent “the desecration of the Christian Sabbath,” delegates attended a statewide Sabbath convention at on December 10, 1845. The next December, hosted a second convention attended primarily by ministers. Fletcher also attended this second convention and spoke in favor of changing the time of commencing courts to Tuesdays instead of Mondays, thereby removing the need to travel on Sundays.

Addressing the convention, Fletcher noted that most northern railroads and canals had stopped operating on Sunday and that “scarcely a post office in the whole land… is open on Sunday.” He concluded that a request from the convention to the legislature for stronger Sunday laws “would come with great moral force” since “the people are now more disposed to regard the Sabbath, than ever before.”

On January 15, 1877, the city council adopted “an ordinance prohibiting (upon the first day of the week commonly called Sunday) any person from conducting any theatrical or Negro minstrel exhibition, or engaging in any such exhibition as actor, doorkeeper, usher, manager, or in other capacity.” Violations brought maximum fines of $50.

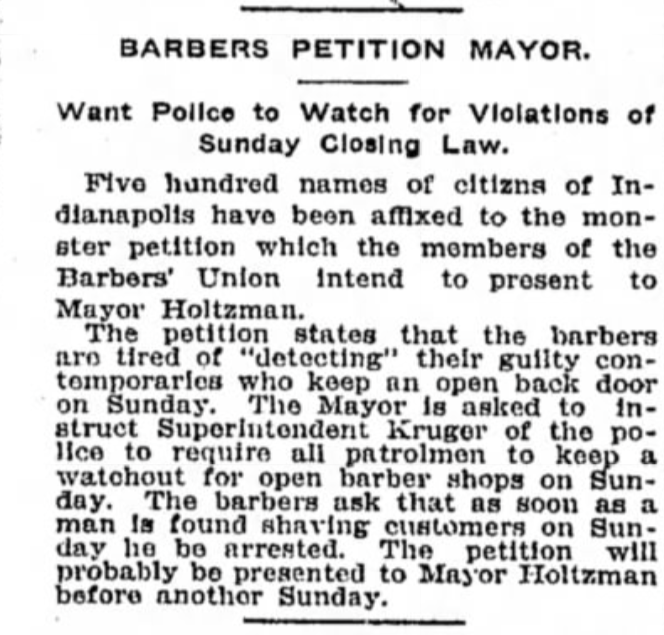

Statewide Sunday laws were expanded over the years and included with the recodification of criminal laws in 1905. In Indianapolis, although the revised general ordinances of 1904 continued to include the 1837 law, the city faced new challenges from theaters, barbers, and baseball in the early 20th century. Local barber William Armstrong, the proprietor of the shop, challenged the state’s 1907 Sunday Barber Law, but a judge found the law to be constitutional.

The issue of Sunday baseball created a major confrontation between legislators from Marion County, who regularly introduced bills to allow the hometown to compete on Sundays, and representatives from the rest of Indiana. In 1907, Thomas W. Brolley, a Catholic Democrat from Jennings County failed to secure passage of his bill allowing Sunday ball games.

Two years later, the Brolley bill passed both houses, but it was vetoed by Governor Thomas R. Marshall; the General Assembly subsequently overrode the governor’s veto. Thus, after an 18-year battle, which included organized protests from the Christian Endeavor Union and the Ministerial Association of Indianapolis, the Indianapolis Indians were finally allowed to play Sunday ball. Their first Sunday game, on April 18, 1909, drew nearly 8,000 fans.

In May, Marion County Superior Court Judge James A. Pritchard declared the bill unconstitutional. Indianapolis Indians manager Charles Carr was subsequently charged with desecrating the Sabbath and arrested. Although tried, convicted, and fined $1 after the season ended, Carr successfully appealed his case to the state Supreme Court. Through the legislative session of 1919, there were numerous unsuccessful efforts to repeal the Brolley bill, including an attempt to outlaw all forms of activity on Sunday.

In October 1909, local movie theater owners, who had been among those who had founded the Citizens Charity Organization, sponsored a charity event on Sunday despite the 1877 ordinance that prohibited theatrical productions. Following the arrest of a local theater owner, a jury found him not guilty, thus establishing a precedent for theater operations on Sundays.

By November 1910, more than 50 movie picture shows had opened on Sundays, and vaudeville theaters and playhouses maintained Sunday hours by showing movies. Nevertheless, for another decade, police occasionally arrested theater managers and actors who performed on Sundays.

Although legislators attempted to change the laws, the 1905 statute remained in effect for decades. Local groups such as Respect Sundays, Inc. (1958), which garnered support from over 100 Protestant churches in Marion County, and Citizens for Sunday Freedom (1963) were established. The late 1950s also witnessed an unsuccessful attempt to “encourage” the county’s grocery stores and supermarkets to close Sundays.

In May 1961, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that similar Sunday closing laws in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Maryland were constitutional. After authorities in Lake County, Fort Wayne, and South Bend began enforcing Sunday closing laws, Marion County officials announced in early October that they would begin enforcement of local laws within two weeks.

Two groups of merchants immediately secured an injunction. Stores previously opened on Sundays but closed after the announcement of enforcement began to reopen. Those not traditionally keeping Sunday hours, including downtown stores, also began to open, citing competition as the principal reason.

Within a few years, the majority of retail shopping areas had Sunday hours, and the police announced they would only enforce the law if the public demanded it. A new Sunday Closing Bill, which would have prohibited the operation of most retail businesses on Sunday, died after it failed to pass the Indiana Senate in February 1976, and the controversy finally subsided after 150 years.

In 2011 Indiana Senator Phil Books sponsored legislation to roll back Blue Laws that prohibited secular activities on Sundays, namely the purchase of carry-out alcohol and the sale of vehicles. Car dealers voiced opposition to the proposal citing the inability to acquire loans and car insurance on Sundays. Liquor store owners objected to the legislation since it would create competition with grocery and drug stores.

The sale of Sunday carry-out package liquor became legal in 2018. Governor Holcomb repealed the Prohibition-era ban and signed the bill into law on February 28, 2018. The second part of Books’ bill which pertained to vehicle sales remains stalled, though some vehicle sales may occur if the buyer holds a special event permit or the person is in the business of buying, selling, or trading a motorcycle or non-self-propelled or non-motorized campers or trailers.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.