During the 70-plus years that Indianapolis had operating , it experienced two major strikes by street railway employees. The first raised the issue of the importance of public services versus the protection of private property rights. The second created a state of near anarchy in the city.

1892 Strike

On January 1, 1892, the president of the Indianapolis Citizens Street Railway, John P. Frenzel, requested that company employees return the badges that allowed them free streetcar transportation even when not working. This move angered laborers already resentful about their long workday.

On January 4, 1892, they began a strike against the company. Eight days later, M. M. Dugan, president of the Brotherhood of Car Drivers, Motormen, and Conductors of Indianapolis, offered to end the strike if the company would agree to an arbitration on worker grievances. Following nine days of idle streetcars, the company responded favorably, and the men resumed work at 11 P.M. on January 14, 1892.

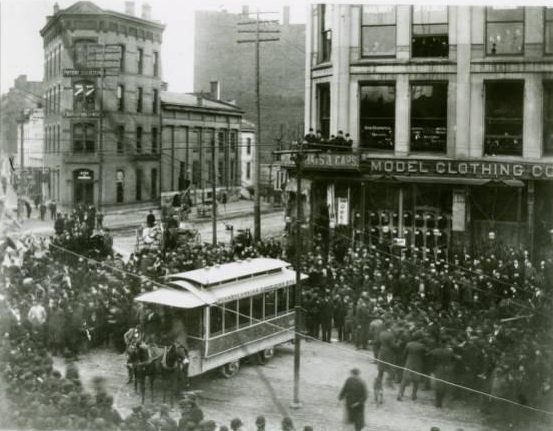

Although the company returned the free-ride badges to workers, it did not address their other grievances about wages and the length of the workday, so the strike resumed on February 21. Striking workers physically prevented the company from moving the streetcars, even after city policemen were brought on board the cars to disperse strikers.

Two days later, , a prominent Republican attorney, filed a complaint with the Superior Court requesting that the court place the streetcar company in receivership. Fishback claimed that he acted on behalf of himself and “thousands” of Indianapolis citizens who were being harmed by the lack of public transportation. That night, Superior Court Judge N. B. Taylor appointed a receiver for the company on the grounds that it had failed to fulfill its contract with Indianapolis citizens to provide regular transportation. After this action, the strikers resumed work.

On March 4, 1892, the crisis seemingly over, the court ordered that control of the streetcar company be returned to Frenzel. Although no further concessions were made to workers, the drivers and motormen chose to remain at their jobs, fearing that they would gain nothing by resuming the strike.

1913 Strike

In August 1913, labor organizers from the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America attempted to unionize Indianapolis Traction and Terminal Company trainmen. Since 1899, the organizers had found a receptive audience in the employees of the Indianapolis Street Railway Company, a division of the Traction and Terminal Company, whose long hours and low pay made them prime candidates for unionization.

Fearing this union agitation, the railway company hired men to follow the labor organizers. Although the company refuted claims that they had armed their agents, violence occurred between the two groups and resulted in injuries to the union men. On October 31, 1913, pro-union employees struck the company.

That night, union sympathizers attacked workers who resisted the job action. The striking employees vandalized streetcars and effectively closed down business. The following day, 65 crews reported to work, but strikers prevented the movement of the streetcars and demanded that employers recognize the union.

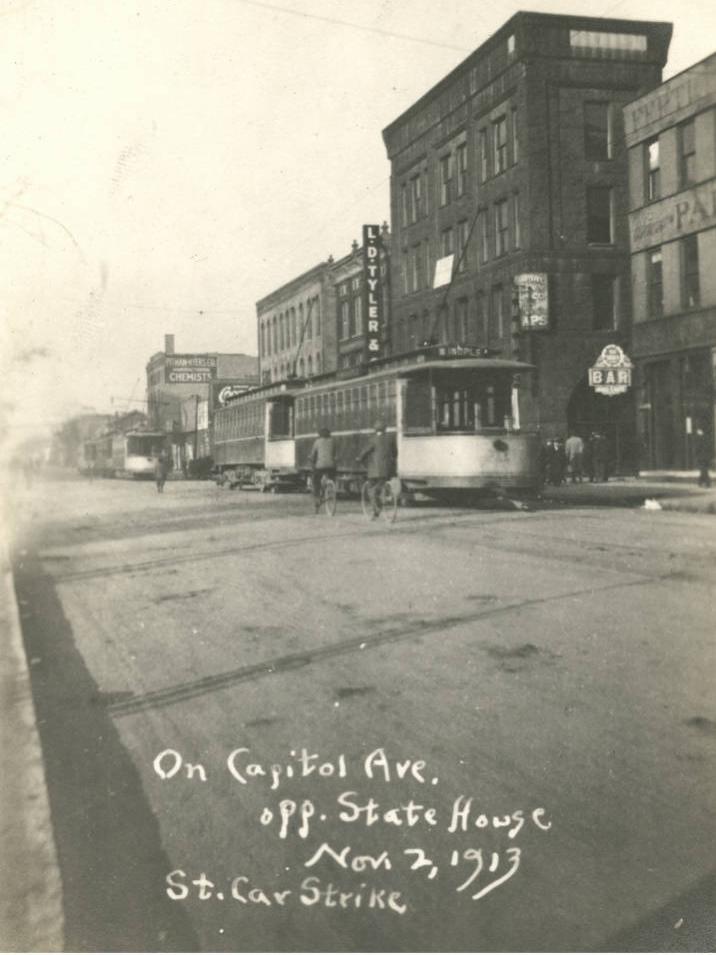

When the company imported strikebreakers from Chicago, one man was murdered and others were beaten in the resulting violence. Although city police were enlisted to control the disorder, some officers refused to ride the streetcars with the strikebreakers. Damaged cars littered the tracks of the city and citizens had to use bicycles and wagons as conveyances. On November 3, agitators stoned the railway company’s president and superintendent. By November 4, Governor Samuel Ralston had ordered 2,200 national guardsmen, the state’s entire contingent, to the city to control the violence.

Three days later, meeting separately with union men and company officers, Ralston formulated a plan to end the strike. Counterproposals from both the company and union were melded into a final agreement that called for the return to work of all employees not involved in the violence, including those discharged by the company.

Any employee not reinstated could present his case before the Public Service Commission (PSC). The agreement allowed workers to present grievances to the company and, if the grievances were not addressed, to refer them to the PSC, which would hear them within 30 days. The PSC’s decisions would be final.

The employees voted unanimously in favor of accepting this agreement, and the strike ended at 6 P.M. on November 7, 1913. The strikebreakers, shielded by National Guard troops, left the city by train.

On November 14, an employee committee presented its 23 grievances to the company. When the company refused to address the list, the employees took their requests to the PSC. The commission’s Court of Arbitration heard 153 witnesses, representing both company and employee interests, during the next seven weeks.

On February 9, 1914, the court presented an 80-page report. Among its decisions: the company was to increase employee pay; reduce the workday to nine hours; give motormen and conductors one Sunday per month off work; and grant the employees the right to organize in a union. It also required that there should be a three-year period before employees could again strike.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.