Through the years, public sculpture in Indianapolis, often quite visible but largely unnoticed, has followed trends typical throughout the state. It may be categorized into three broad areas—commemorative, religious, and aesthetic—although some pieces defy classification.

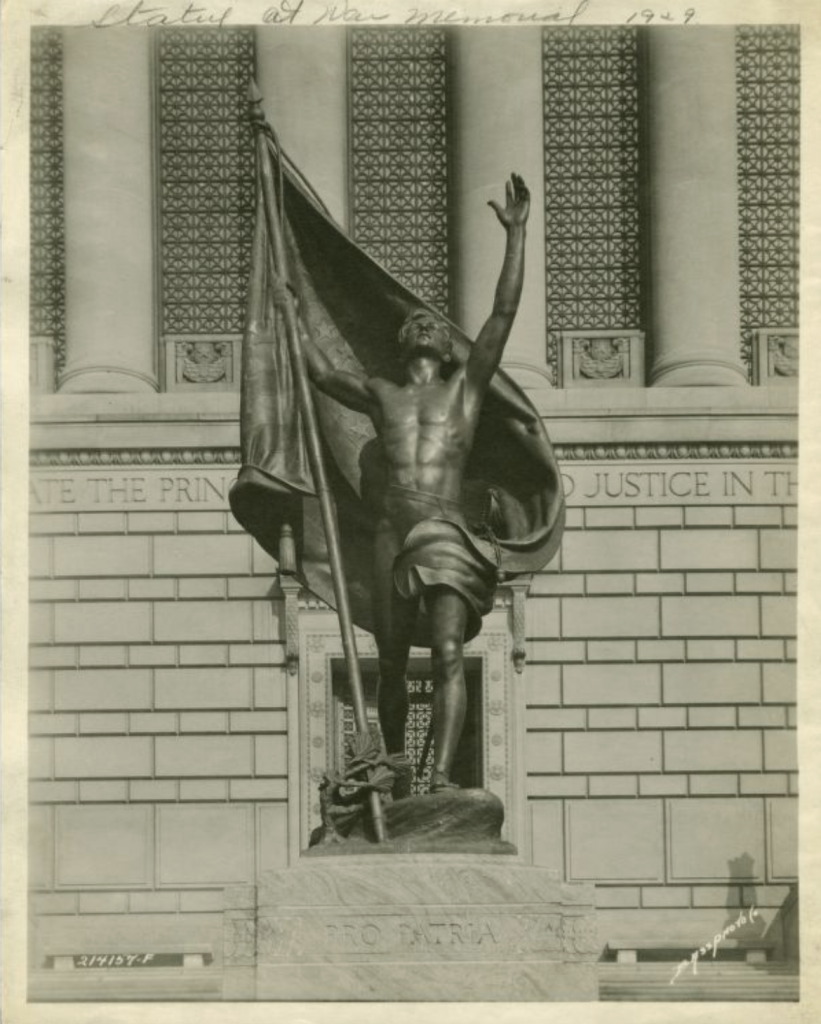

Commemorative sculpture first became popular after the with a proliferation of monuments to Indiana’s soldiers in towns and cemeteries throughout the state. Indianapolis was no exception. Dominating downtown as well as , the gargantuan was completed in 1902. Wars preceding the Civil War are included on the monument; later conflicts have their own memorials. is commemorated with an imposing building that includes heroic sculptured figures in a Classical frieze, as well as the bronze giant (1929) by Henry Hering. Hering also designed the four bronze relief panels on the Obelisk north of the and the seated figure of Abraham Lincoln (1934) in .

Indianapolis contains numerous heroic bronzes honoring national notables with Indiana connections, with Lincoln being the most obvious example. A very different depiction from that of Hering stands outside the , the (1963) by . The grounds, the Circle, and University Park have the greatest concentrations of such statues. Among the first Indiana figures to be immortalized in bronze was the unlikely Schuyler Colfax, a piece no doubt more important as a very early work (1887) of the famous sculptor Lorado Taft.

Bronze versions of Civil War governor are prominent both at the State House and on the Circle. These works are by noted sculptors and , respectively. Schwarz was the primary sculptor of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Two of the surrounding statues on the Circle are Mahoney’s work: George Rogers Clark and William Henry Harrison. Perhaps the most interesting commemorative sculptures honor anonymous figures, such as the (1924) in by , one of a handful of female sculptors working in Indiana in the early 20th century. John Szabo sculpted a detailed statue of a coal miner, erected on the west lawn of the State House in 1969.

is a sometimes overlooked collection of sculptural art, either commemorative or religious in theme, such as the Forrest monument by Rudolf Schwarz, depicting a woman in repose. Other cemeteries in the area, too, are repositories of sculpture; a fine tribute to the heroes, , stands in Washington Park Cemetery (see ). Religious sculpture may also be found at churches and religious institutions. Some particularly fine examples include Joseph Quarmby’s (1871) on downtown and Adolph Wolter’s (1959) on .

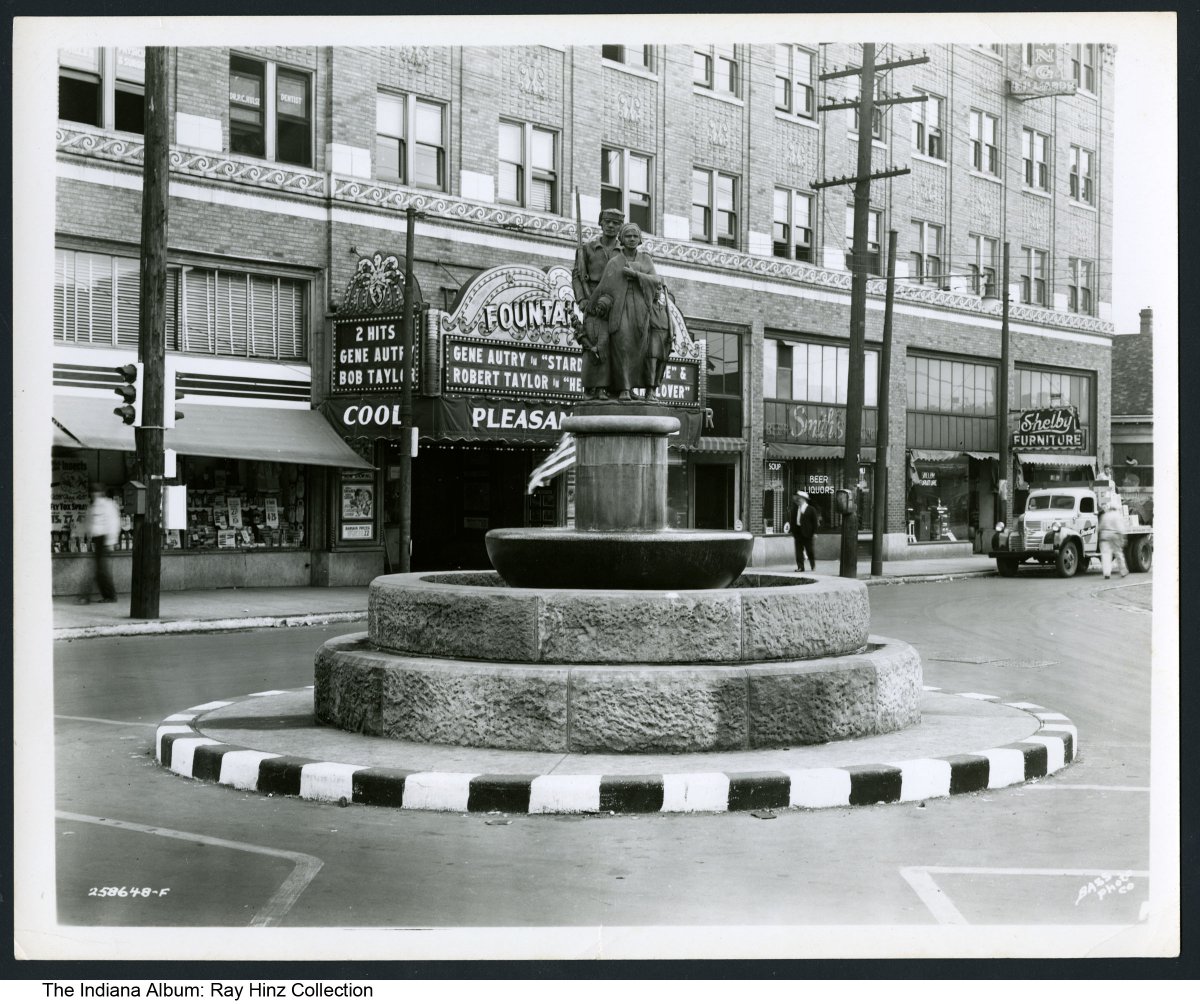

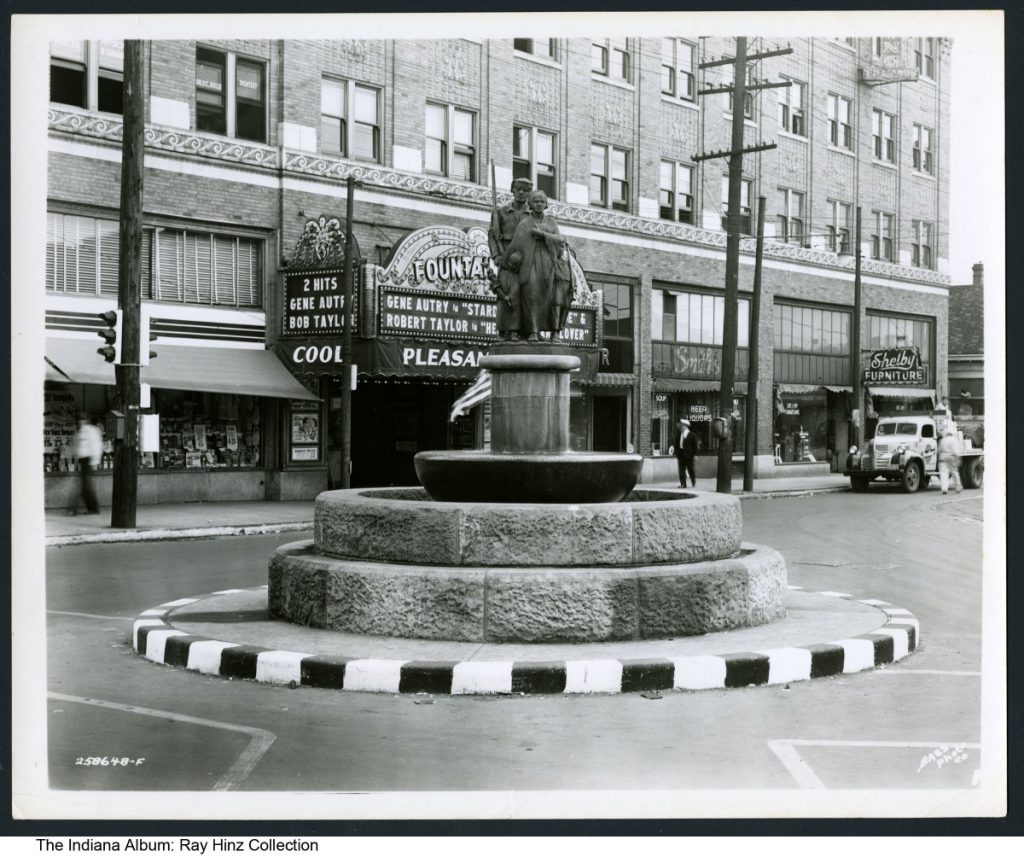

Aesthetic sculpture—or sculpture for art’s sake—was almost nonexistent in the sense we know it today before World War II. Exceptions include Stirling Calder’s Depew Fountain (1919) in University Park. Another example was the collection of ornate ironworks in , where lifesize lions guarded every entrance. Once there were nine fountains, three of which, since recast, today grace the intersections at Cross Drive.

Until about 1930, buildings often sported noteworthy decorative sculpture, using Classical or other “artistic” themes. The cornice line of the on the Circle featured medallions sculpted by Henry M. Saunders depicting members of the English family and several Indiana governors. The surviving medallions appear today as individual sculptures in a half dozen county seats in Indiana. The heroic Greek goddesses that once graced the old Marion County courthouse suffered a similar fate. Two stand as part of in , a work that features another architectural sculpture, Karl Bitter’s , from a demolished building in New York.

View Source

The 1960s witnessed a movement for public art, much of it abstract, such as David von Schlegell’s untitled giant “L”s erected in the late 1970s on the campus. An even more controversial and largely unloved work is Mark di Survero’s (1972), first erected at the , later relegated to a remote location on West 30th Street before plans were made to move the piece onto the grounds of the (IMA), now known as Newfields. The IMA, the , the , and even all exhibit collections of modern outdoor sculpture. Glenna Goodacre’s (1988), an exuberant representational work, is on display at The Children’s Museum.

Corporations have commissioned much of the city’s public sculpture. Among the most controversial is (1987) by Zeno Frudakis at downtown’s Capital Center, a sculpture that consists of a nude male and female. A companion piece, , stands on the other side of the building. John Spaulding’s joyful (1989) stands at the entrance to today’s . Corporate-backed art continued in the 1990s, as represented by Lyle London’s abstract in front of the newly constructed Indiana Insurance Company building.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.