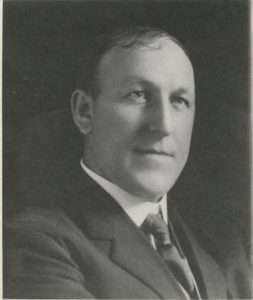

Photo info ...

Credit: Bass Photo Co Collection, Indiana Historical SocietyView Source

(Jan. 23, 1872-Sept. 24, 1927). Born in Marion County, Samuel Lewis (Lew) Shank worked at a variety of jobs before entering politics. In 1902, he successfully ran for county recorder on the ticket. In 1909, he was elected mayor for the first time. During his tenure, he gained national fame by auctioning carloads of farmers’ vegetables to consumers from the steps of city hall. Thereafter called the “potato mayor,” he considered his auctions a means of fighting what he called unfair pricing by wholesalers.

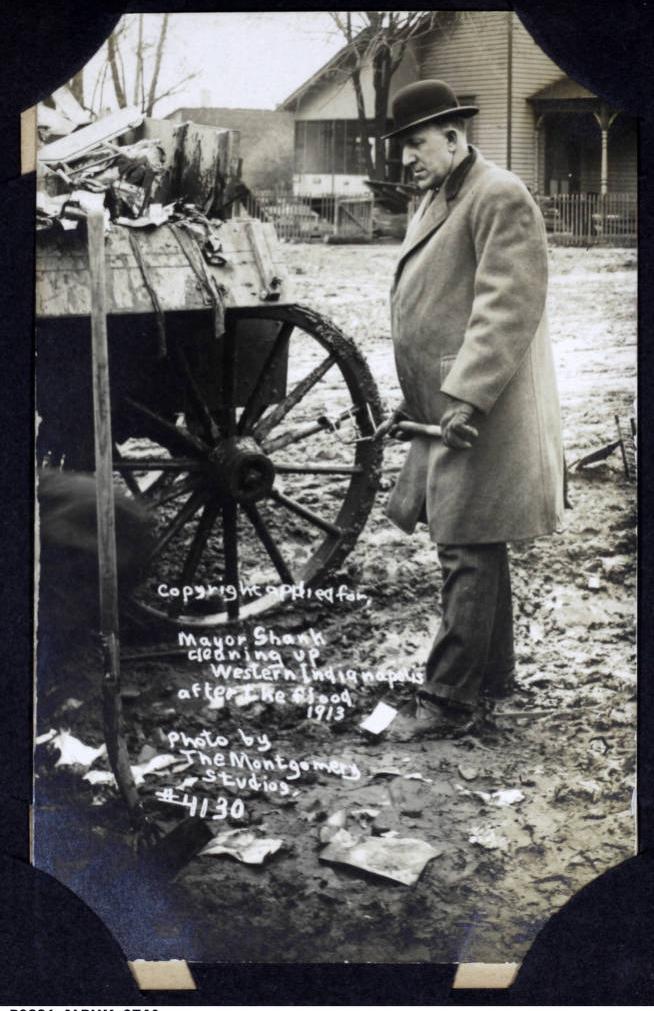

Shank crusaded against Sunday saloon openings, appointed a vice commission, and supported women’s suffrage. His last year in office saw a series of natural disasters and political conflict, including the 1913 flood and the 1913 streetcar and teamster strikes. During the street railway strike many policemen, sympathetic to the strikers, mutinied, refusing to man the streetcars and protect the strikebreakers who operated them. In turn, Shank refused the governor’s request that he order the policemen to assume their stations on the cars (see , 1892 and 1913).

Four weeks before his term ended, Shank resigned his office in the midst of threatened impeachment proceedings over his encouragement of the earlier police mutiny. However, one contemporary noted that the chances of impeachment were slim to nonexistent and suggested that Shank may have resigned as a publicity stunt. He already had signed a contract to go on the circuit with a monologue about his time as mayor. Shank performed in vaudeville for 26 weeks after leaving office, opening in Kansas City before performing for 14 weeks in New York City. Although his act featured his monologue, it also included a trained horse.

After his return to Indianapolis, Shank ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 1918. In his last campaign, beginning in 1921, his wife Sarah was his campaign manager. Shank’s “me and Sarah” speeches were widely known for their colloquial language and common man themes. Shank won the election with the largest majority in Indianapolis’ history to that time. This electoral mandate, however, did not lead to a smooth second mayoral term for Shank as he opposed the , which became the dominant force in politics in the city during the 1920s.

In 1921, Shank made the first local radio speech on Indianapolis’ first station, . He also led a group of hundreds of marchers to the State House to protest the Public Service Commission’s grant of a rate increase to the , which he counted as an important success during this time in office.

Shank failed to stem the power of the Ku Klux Klan. At least 27 percent and perhaps as many as 40 percent of all native-born white men in the city paid 10 dollars to become official members of the Klan during this era. A separate women’s organization (Women of the Ku Klux Klan) also existed and may have been quite large, although the actual extent of its popularity is not known. Shank prohibited masked parades, refused the use of for a Women of the Ku Klux Klan rally, and enforced the Board of Public Safety’s ban on cross burnings. In July 1923, a cross burning in attracted several thousand people and produced a rock-throwing incident when city firemen attempted to extinguish the fire.

In an effort to break the Klan statewide, Shank entered the Republican gubernatorial primary against the Klan’s candidate, Ed Jackson. In the May 6, 1924, primary election, Jackson easily gained the nomination over Shank and other anti-Klan Republicans, defeating the Indianapolis mayor in Marion County by a total of 38,668 to 20,306 votes.

Following his defeat, Shank reluctantly capitulated to the Klan’s political power. He allowed the Klan to hold a massive victory parade, which saw more than 7,000 triumphant Klansmen and Klanswomen march from the Indiana State Fairgrounds on the northside of Indianapolis, through the Black neighborhoods along , into the center of the city. The Klan threatened to impeach Shank, accusing him of aiding bootleggers and criminals.

Near the end of his second term, Shank constructed the Shank Fireproof Storage Company, an auction warehouse on North Illinois Street. He sometimes left the mayor’s office for a few hours to conduct auctions there.

After leaving office the second time in January 1926, Shank appeared for one week at an Indianapolis vaudeville theater before settling into a career as an auctioneer and public speaker. Shank was planning to run in the 1928 election for the 7th district congressional seat when he died.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.