Riverside Amusement Park, located on West 30th Street at and adjacent to Riverside City Park began as a joint venture of Pittsburgh investor and amusement park developer Frederick Ingersoll and Indianapolis businessmen J. Clyde Power, Albert Lieber, and Bert Feibleman. By 1903, the park contained a “double eight toboggan railway” and numerous concessions. The owners soon added the “Old Mill,” a replica of a working flour mill through which passengers rode in boats and were entertained by electrically lighted scenes.

Riverside grew in popularity by capitalizing on the “Coney Island craze,” spurred by the famed New York City amusement park, and adding new amusements, including a 350-foot-long “Shoot the Chutes” waterslide, reputed to be one of the steepest and most terrifying in the country. During the early years, the park also featured a zoo. Visitors could also sunbathe, swim, or launch sailboats and canoes from the banks of White River.

Competing with other Indianapolis amusement parks, and , business manager J. Sandy increased park attendance by not charging an admission fee. Riverside instead relied on revenues generated from individual rides and concession leases. Sandy introduced live entertainment, such as “Buckskin Ben’s Wild West Show” and the “Famous Cowboy Band.” He also arranged for additional streetcar service to the park. In 1906, trollies arrived at the entrance to the park almost every three minutes.

In 1919, attorney Lewis A. Coleman organized the Riverside Exhibition Company and gained control of the business. Coleman had provided legal services for Riverside’s owners for years and took payment in company stock. The new company issued more stock, which allowed expansion and modernization of the park’s amusements. This included two large roller coasters, “The Flash” and “The Thriller,” a 2,200-foot-long miniature railroad, and a string of concrete block buildings that housed games and food concessions.

A key attraction at Riverside was the roller skating rink. Erected in the early 1900s, it first served as a dance hall, attracting thousands on the weekends to dance to live orchestras and dance bands. The hall was eventually transformed into a 100-by-200-foot skating rink, which proved to be an inexpensive and safe place for recreational activities into the 1960s. The park also included a six-story diving tower, which opened in 1910.

Riverside experienced many prosperous years under the leadership of John D. Coleman, son of Lewis, who became president in 1939. Throughout World War II, Riverside sponsored several wartime relief programs to assist families of servicemen, thereby guaranteeing a steady visitation of patrons who wished to demonstrate their patriotism.

Attendance rose into the 1950s as Indianapolis residents became more mobile and acquired more leisure time. In 1952, an estimated 1 million visitors crowded Riverside’s midway and skating rink. During the late 1950s, Riverside introduced several expensive amusements, including an automobile turnpike ride modeled after Disneyland’s popular attraction.

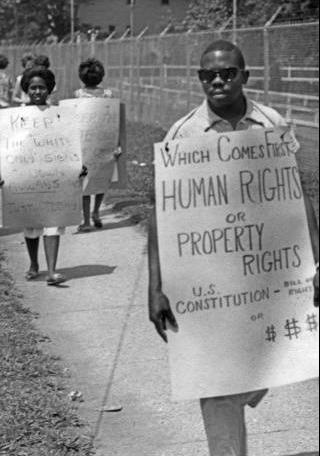

With Lewis Coleman’s acquisition of the park in 1919, Riverside adopted a policy of “whites only patronage,” although African Americans were permitted to visit on designated “Colored Frolic Days.” This discriminatory policy angered integrationists who picketed the park during the early 1960s and eventually convinced John Coleman to remove the “whites only” signs.

By this time, however, Riverside was experiencing serious problems. Reduced revenues heavily affected park maintenance. By the mid-1960s, the park was losing over $30,000 annually. At the end of 1970, Riverside finally closed, and its rides were sold off or demolished. Coleman attributed the park’s demise to the high cost of new rides, maintenance and insurance fees, and the competition from the nation’s major amusement-theme parks.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.