Houses of worship have occupied prominent positions on Indianapolis’ landscape from the rustic village of the 1820s to the rise of suburbia. Design and ornamentation set these buildings apart as sacred places differing in purpose from surrounding structures. Size, architecture, building materials, and location reflect the congregation’s members’ wealth, influence, and tastes. In surveying the city’s rich heritage of religious architecture, only a limited number of extant sacred structures are cited here as outstanding examples of styles or illustrative of trends.

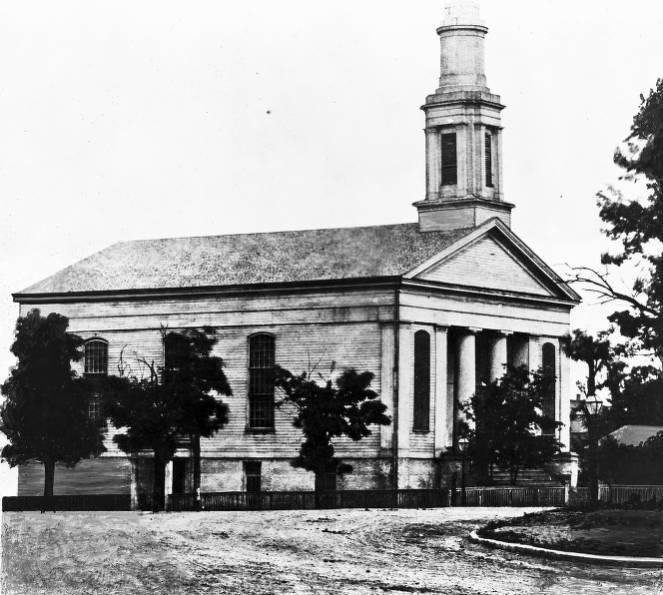

After Indianapolis’ founding in 1820, settlers began establishing congregations within the original . They erected simple churches of wood or brick that were superseded eventually by more substantial structures. By the 1850s congregations of major religious bodies occupied buildings in the favored architectural styles of antebellum America. Greek Revival was most influential, as its model, the Greek temple, was regarded as the ideal building. Four prominent churches built in Greek or classical styles were located on the by the mid-1850s— (1843) and (1840), Christ Church (1838), and Methodist Church (1829). (The buildings no longer exist.) The style gaining influence by the was Gothic Revival, with pointed arches in the window and door casings of simple and elaborate structures. This trend is reflected in William Tinsley’s design of (Episcopal) on the Circle, the city’s oldest extant religious building, a pleasing English country Gothic Revival structure completed in 1859 and superseding an earlier Greek Revival building.

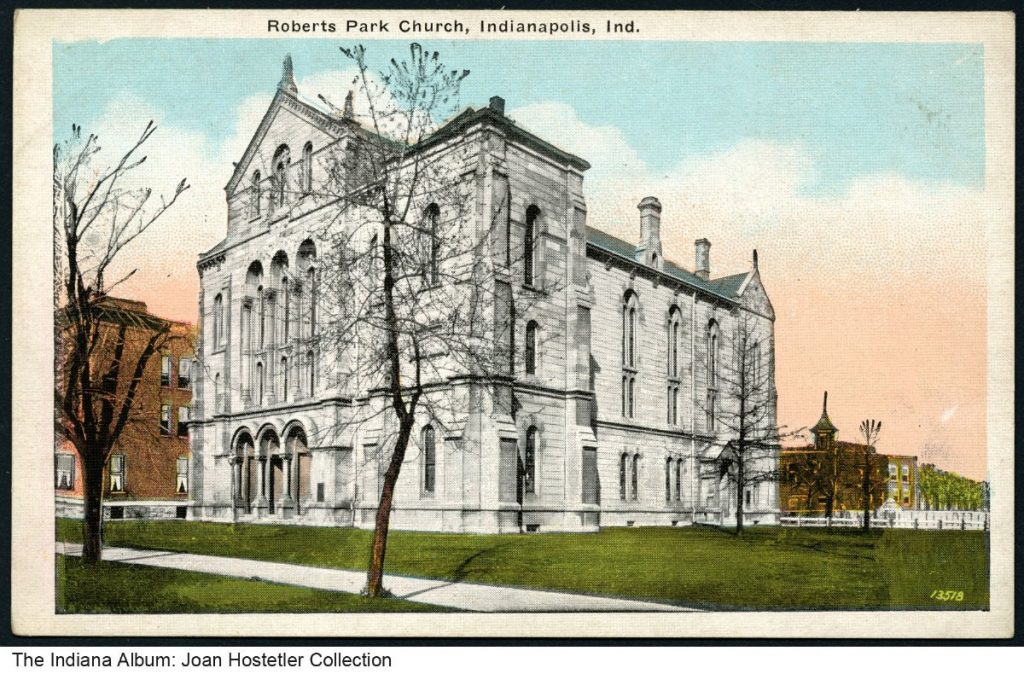

After the Civil War, replacing church buildings and forming new congregations stimulated a wave of church construction. In addition to Gothic Revival, Romanesque Revival with its characteristic rounded Roman arches was an influential style. Red brick was a popular building material with a minority of churches built in stone. Solid and massive in appearance, built close to the street, and most having spires directing attention skyward, the new houses of worship conveyed a sense of religion’s authority in the community.

German immigrant emerged as the most influential late 19th-century designer of churches. His Gothic Revival (1871) was then the state’s largest church. Bohlen’s other structures include the Gothic Chapel at (1875-1877) and St. Paul Lutheran Church (1882). His major Romanesque Revival building is the stately limestone (1876) that resembles the City Temple in London. The Bohlen firm under Diedrich’s son Oscar designed Lockerbie Square United Methodist Church in Romanesque Revival style (1892) and Zion United Church in Christ, a Gothic Revival structure built in 1913.

Gothic Revival churches of other architects include such southside landmarks as the former Fletcher Place United Methodist Church, designed by Charles Tinsley (1872-1880), and Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1883-1891) built by Adrian Wewers. The former Trinity Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church (1872), now the Church of Jesus Christ of Apostolic Faith, is a small neighborhood church that reflects a builder’s interpretation of Gothic Revival of which there were once many examples.

Romanesque Revival buildings of the period include First Lutheran Church (1887), built by Peter P. Cookingham, and Central Christian Church (1892). Williams and Otter of Dayton, Ohio designed Central Avenue United Methodist Church (1891), a magnificent red brick monument. Another southside landmark, Immanuel United Church of Christ, was completed in 1894. St. Bridget Catholic Church (1879) is a builder’s simple version of this style. George Bedell designed several brick Romanesque Revival structures for neighborhood parishes such as the former St. Francis de Sales Catholic Church (1913), now a part of . Historic was remodeled with a Romanesque Revival tower in the 1890s.

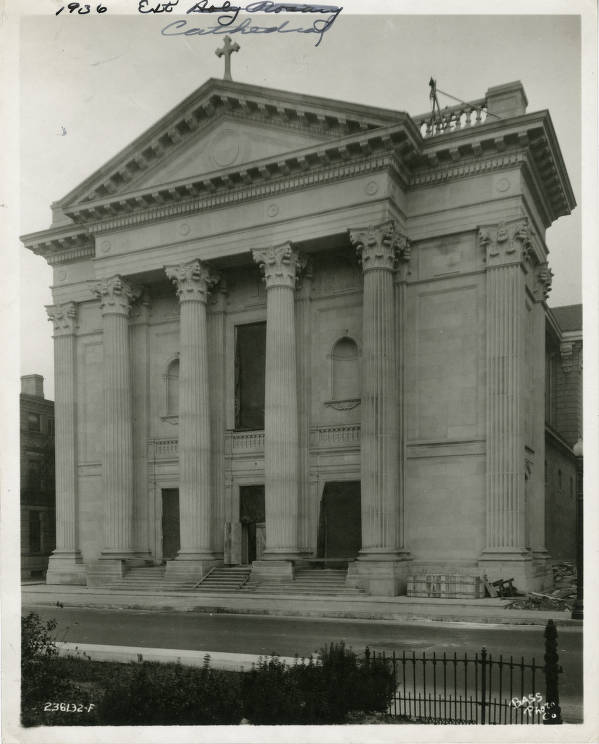

By the early 20th century, Classical styles, especially those reflecting Renaissance influences, reemerged in American church architecture. Catholic parishes in particular were drawn to this style, including (1906-1907), designed by New York architect William Renwick and with a façade designed in 1936 by the Bohlen firm; Holy Cross Catholic Church, an Italian Renaissance structure, Cornelius Curtin, architect, (1922); and Holy Rosary Catholic Church, designed in Neoclassical style by and Kenneth Wooling (1925). St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church (1928-1929) was built in a triumphant Italian Renaissance style with soaring campanile by noted Chicago architect Henry Schlacks. St. Patrick Catholic Church (1928) was designed by in Spanish Renaissance style. The trend can be found in the Assembly Hall of , built in 1912 for Second Church of Christ, Scientist, in a massive Neoclassical style by Solon S. Beman, and Woodruff Place Baptist Church, executed in Italian Renaissance style in 1926.

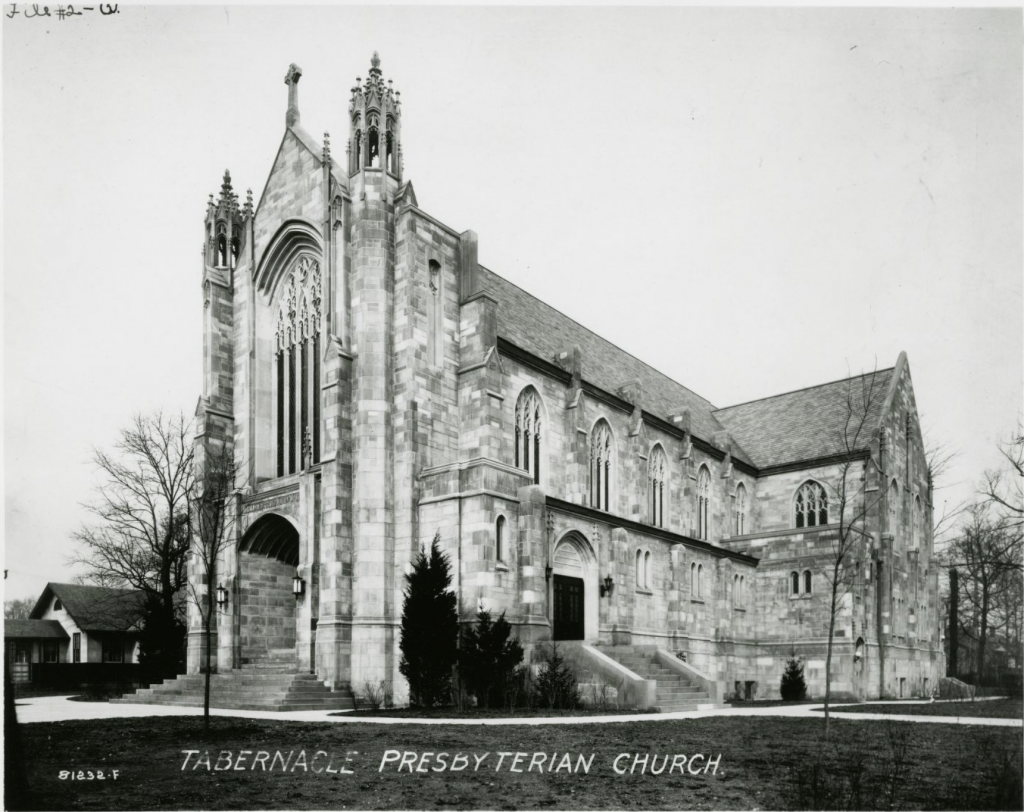

A new Gothic movement emerged in the early 20th century whose leading national figure was Boston architect Ralph Adams Cram. Its partisans considered Gothic the ideal religious architecture as its arches pointed upward to the heavens. Unlike the Gothic Revival forms, the new version imitated more closely the massiveness of medieval French and English Gothic cathedrals with long naves and tall, square towers usually built in stone, not brick. The city’s most imposing edifice in this style is the massive , the design of George F. Schreiber, located downtown along North Meridian Street since 1929. Another downtown example, St. Mary’s Catholic Church, was begun in 1912 and designed by German architect Herman Gaul to resemble the Cologne Cathedral.

Leading Protestant congregations built outstanding Gothic structures in fashionable neighborhoods during the 1920s: First-Meridian Heights Presbyterian Church (1927); Broadway United Methodist Church, a splendid limestone complex designed by (1925); North United Methodist Church (1931), the design of Atlanta architect Charles H. Hopson; (1921), the work of ; and Irvington Presbyterian Church, started in 1928. A variation of the style is the Irvington United Methodist Church, a brick English Gothic gem built by Herbert Foltz (1926).

The Art Deco style with its geometric ornamentation, popular in commercial and apartment buildings of the 1920s, is found in the former Third Church of Christ, Scientist, now Phillips Temple Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, a limestone monument by Robert Frost Daggett completed in 1928.

The and limited church building nationally and locally. After 1945 construction boomed as the suburbs attracted residents forming new congregations and drew old congregations relocating from downtown sites. New houses of worship often adapted traditional Gothic and Romanesque styles for large structures designed with ample meeting and classrooms. Their sites allowed space for parking lots and well-landscaped lawns. The most distinguished building of this trend is Second Presbyterian Church, relocating in 1959 from downtown to a magnificent limestone French Gothic structure designed by McGuire, Shook, Compton, and Richey (see ). American traditions were affirmed in the new interest in Colonial Revival or Neo-Georgian buildings through the 1950s. A harbinger of this trend is the elegant Fourth Church of Christ, Scientist, in , begun in 1936. The most imposing example is the Meridian Street United Methodist Church, a red brick Georgian Revival complex completed in 1952 by architects William Russ and Merritt Harrison.

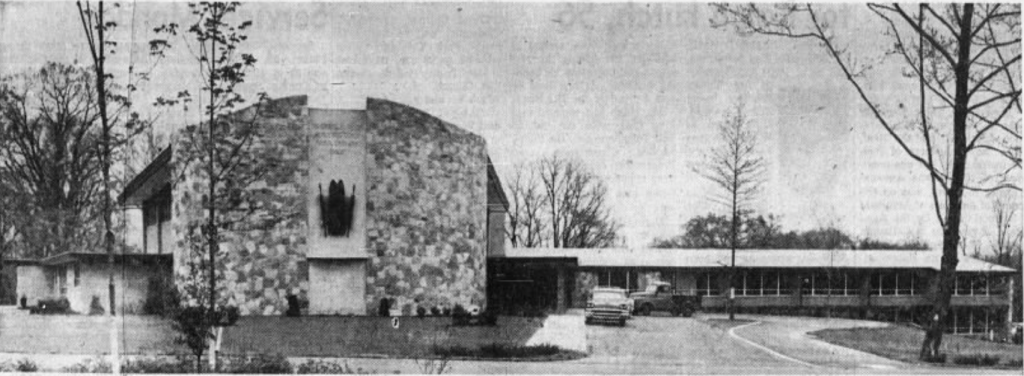

In the late 1950s, several congregations showed some daring by breaking away from traditional styles in favor of adapting current trends in modern architecture. A functional approach informed some interior arrangements as architects devised seating to allow worshippers to be closer to the center of religious ceremonies. Some noteworthy buildings reflect this modern trend. The was completed in 1958 in a striking contemporary design. was designed in a contemporary style using Romanesque arches by McGuire, Shook, Compton, and Richey (1960). Third Christian Church (1963), designed by James Associates, echoes some elements of modern formalism. St. Luke’s United Methodist Church (1960s) by Edward Dart makes imaginative use of skylighting. The steep-pitched, A-frame roof popular in many suburban churches is found in Friedens United Church of Christ (1967), designed by James Associates (see ). St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church, a design of Woollen Associates (see with hexagonal floor plan and lighting from above, was completed in 1970.

The recent era’s most distinguished complex of modern religious buildings is the , built in stages from the 1960s with the library completed in 1977 and Sweeney Chapel in 1987. World-class architect Edward Larrabee Barnes’ design reflects Middle Eastern architecture from the time of Christ.

Through the decades the city’s religious buildings have generally followed national trends in architectural styles. The cycle of urban growth and development has affected sacred structures as it has the rest of the built environment. Such change has caused the elimination of Greek Revival and the earliest Gothic Revival styles of buildings that evoke the antebellum past, reduced the concentration of churches once numerous in the central city, and dispersed religious buildings across the metropolitan area. Sacred structures now neither appear as prominent on the landscape nor do they provide the sense of ubiquity of sacred places in the built environment that they did in the 19th century.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We seek an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.