For most of the 19th century, no hospital existed in Indianapolis. The city’s residents associated hospitals with facilities where people with long-term illnesses went to die. The medical profession was built around private practices.

Only when epidemics seemed poised to ravage the city did interest arise in a permanent health care facility. Indeed, Indianapolis did not see the need for medical facilities until after the Civil War. City Hospital (which eventually became ) came out of fear of a smallpox outbreak in 1855 but over the objections of some residents who did not want it located near them. Even after it opened in 1866, residents viewed City Hospital as a place for the city’s poor and destitute to receive medical attention and yet still as a last resort.

The Rise of Religious Health Care Institutions, 1880s-1890s

However, these attitudes began to shift as religious institutions became interested in promoting health care. Roman Catholic Bishop had studied medicine before entering the priesthood and was shocked that Indianapolis had no real hospital. In 1881, the bishop asked the Sisters of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul to organize a hospital for the city’s . After several years on East Vermont Street, opened a new 40-bed facility at South and Delaware streets in 1889. Not only did the city’s Catholic population’s needs soon outgrow the new facility (as well as the Sister’s decision to serve people regardless of faith—a decision that overcame some initial anti-Catholicism) but also the city’s Protestants soon began organizing medical facilities of their own.

In 1895, the city’s German Protestant churches launched the Protestant Deaconess Hospital and Home for the Aged. The hospital opened at 200 North Senate in 1899. Female volunteers who received medical training, as well as room and board from the hospital in exchange for their work, served as the facility’s primary caregivers. Although the institution eventually received support from most of the city’s Protestant churches, until it closed in the early 1930s, some believed that churches needed to make an even larger commitment on behalf of those in need.

Methodist Hospital of Indiana, 1908-

No sooner had Deaconess opened its doors than Indianapolis Methodist churches banded together to begin a fundraising campaign to construct a new hospital for the city. While some opposed it, most of the city’s held that “the Church does not dare stop until it encompasses all the interests of Jesus Christ and our Church can never encompass all His interests and leave out our sick people.” The Methodist hospital board initially selected a location at Illinois and 29th streets. Its members, however, found raising funds more difficult than initially anticipated and faced opposition from some of the city’s doctors for buying land so far from downtown.

Eventually the board purchased a different parcel at Capitol Avenue and 16th Street and redoubled its efforts to get Methodists to donate money to support the new hospital. On October 25, 1905, devout Methodists, including the vice president of the United States Charles Fairbanks and U.S. Senator Albert Beveridge, attended a cornerstone-laying ceremony. On January 1, 1908, 5,000 people attended Reception Day where Indiana’s governor, J. Frank Hanly, and others greeted them. The hospital officially opened at the end of April, with 65 beds (including 37 that were private) and a state-of-the-art elevator.

Catholic Health Care Institutions in the 20th century

Not to be outdone, on February 3, 1913, St. Vincent opened a new, 325-bed, hospital facility, at Fall Creek Parkway, between Illinois and Meridian streets. The hospital had watched its neighborhood become increasingly industrial, and the city’s population was shifting further north, prompting the move.

In 1914, St. Francis hospital opened its doors in Indianapolis. In 1875, in the midst of the Kulturkampf in Germany, Catholic sisters were invited to the United States to continue their ministry in the American Midwest. Their first hospital was in West Lafayette. Eventually known as the Sisters of the Perpetual Adoration of St. Francis, the order spread to Indianapolis and beyond. Their became a prominent fixture on the city’s southside.

By the mid-20th century close to half of all the babies born in Indianapolis entered the world at St. Vincent’s. The hospital moved north again in 1974, this time to 86th Street, selling its Fall Creek Parkway property to .

The Role of Chaplaincy Services in Health Care

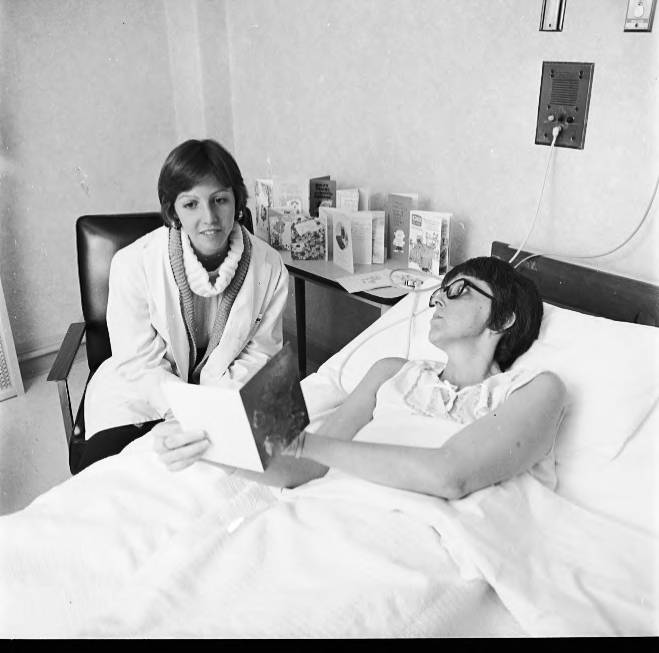

Faith is not just a part of hospitals founded by religious groups. Indianapolis’s hospitals boast robust chaplaincy services that are ready not only to provide spiritual care and support for patients and their families but also to hospital staff. For many years, starting in the 1920s, the was responsible for helping coordinate chaplains for the city’s hospitals (at least for those run by the city or Protestants). Now, however, the hospitals take a more active role in securing chaplains. Additionally, chapels are a common part of both secular and religious hospitals, a place for prayer and quiet contemplation for people facing some of the greatest joys and sorrows in the human experience.

The Raphael Health Center

In the early 1990s, (Tab), located at 34th Street and Central Avenue, was instrumental in founding the Mapleton Fall Creek Christian Health Center. The church helped to establish the clinic with the goal of providing “community centered, quality, affordable health care and related services” to residents in the neighborhood surrounding it.

Though separate from Tab, the church provided financial and spiritual support to the community clinic, and early Tab volunteers served as its board members. Incorporated in 1994, the community health care center was granted 501(c)(3) nonprofit status in June 1995. In the late 1990s, the Indiana State Department of Health and local donors and philanthropic organizations provided additional financial support that allowed for the growth of its facilities and for the hiring of full-time staff.

In 2002, Mapleton Fall Creek Christian Health Center became the Raphael Health Center. At the same time, it acquired the status of a federally qualified health center. Such centers must be in underserved areas, offer a sliding fee scale, provide comprehensive services, assure care quality, and have a governing board of directors. The center is located across the street from Tab on the southwest corner of 34th Street and Central Avenue.

Religious Health Care Institutions in the 21st Century

By the 21st century, Methodist, St. Vincent, and St. Francis hospitals had all become part of or transformed themselves into larger health care networks. Methodist merged into the IU Health system, while St. Vincent became part of Ascension, and St. Francis forged a network of its own. Despite these changes, all three have retained faith as part of their health care mission.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.