Beginning in the East as a result of announced wage cuts, the railroad strike of 1877 spread west quickly. Freight trains on most lines came to a standstill, including those at Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Cleveland, Columbus, and Indianapolis. The labor uprisings that affected the nation’s railroads were larger and had more serious consequences than other strikes during the economic depression of the 1870s. The strikes were largely a manifestation of frustration and desperation in the face of steadily worsening economic conditions over which workers had no control.

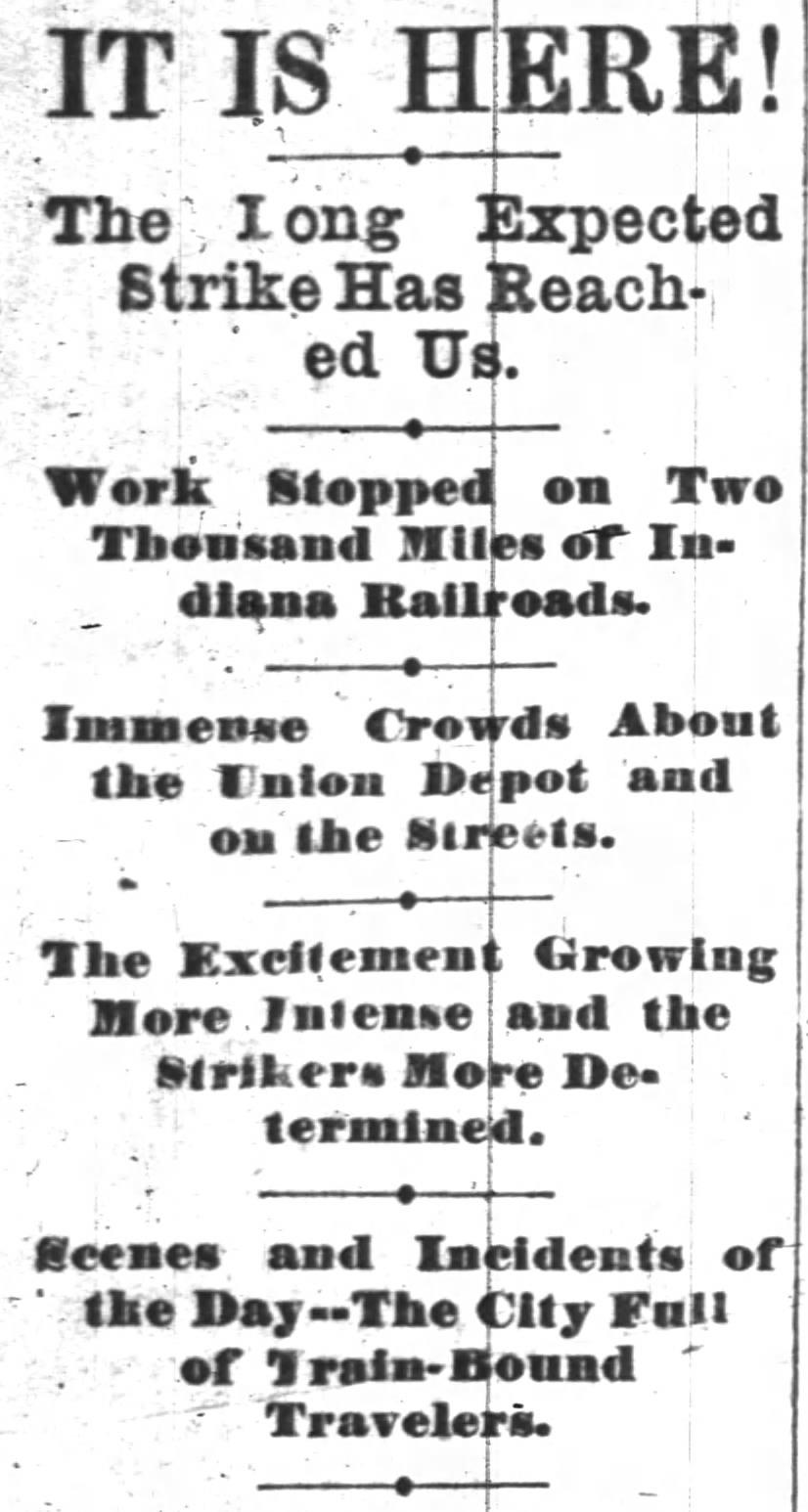

On Saturday, July 21, 1877, union workers assembled in the courtyard of the Indiana State House to rally in support of their eastern counterparts, causing work stoppages in Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, Terre Haute, Evansville, Elkhart, and Vincennes. Passenger trains initially were allowed to run, but later all rail transportation throughout Indiana was paralyzed. Both Mayor and Governor James D. Williams adopted a conciliatory attitude toward the strikers, refusing to use force.

Railroad operators, unable to persuade the governor to involve the militia, turned to Federal District Judge to remedy the situation. The operators could pursue this strategy because several of the railroad lines were in receivership of the federal courts. Gresham, who was less sympathetic with the strikers, asked President Rutherford B. Hayes to send troops to Indianapolis to control the strikes but was informed that none were available.

As a U.S. marshal, Gresham possessed the authority to call for whatever assistance was needed to protect life and property, and the unique situation of this strike made it a federal offense. He declared that the situation in Indianapolis was critical and dangerous, and he organized a , which included ex-governor Conrad Baker, Senator Joseph E. McDonald, and future president . When President Hayes sent troops in support of Gresham’s efforts, it marked the first time that federal troops had been involved in a national labor dispute.

Governor Williams took a similar stand and issued a proclamation declaring that the strikes threatened the peace of Indianapolis and that the strikers’ grievances should be remedied in the courts. He asked the strikers to withdraw and formed an arbitration committee to assist in the settlement of the strikes. Judge Gresham ordered the strikers back to work, and the strike began to collapse, finally ending on August 1. Most of the workers returned to work without any promise of wage restoration. When the freight trains resumed operations in Indianapolis, federal troops were present to prevent any violence or disorder, though their services were not needed.

Fifteen strikers were arrested on July 27 and charged with contempt for interfering with the operation of railroad lines. These men were tried with no jury in federal court by Judge Thomas Drummond. Of the 15 arrested, 13 were found guilty and sentenced from one to six months in jail; one was acquitted and the other freed with one year of good behavior as well as a $5,000 bond ($123,000 in 2020).

The strikers regarded these arrests as a betrayal of pledges made by the arbitration committee during the strike. After public denouncements and the threat of impeachment, Drummond released the convicted men on $500 recognizance each, with the stipulation that they refrain for one year from interfering with property in control of the federal courts.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.