Public utility services are of recent origin, gradually evolving into their current form over the last century or so. Indianapolis developed its utility infrastructure when its population grew large enough to need gas, electric, communications, and water services.

Gas

Indianapolis was a rapidly growing railroad hub in 1851 when gas lighting made its first appearance in the city. Two years later the city contracted with the newly organized Indianapolis Gas Light & Coke Company (IGL&C) to light several blocks of Washington Street. By the end of the decade, coal gas lights illuminated most of the city’s downtown streets. Gas was in demand for domestic and commercial use, too. Unlike wood, coal, or whale oil, its use produced neither ashes, smoke, nor soot. IGL&C was the city’s only gas producer until 1876 when Citizens Gas Light & Coke Company began operation. The new company met a sudden end, however, when its gas works exploded in 1877.

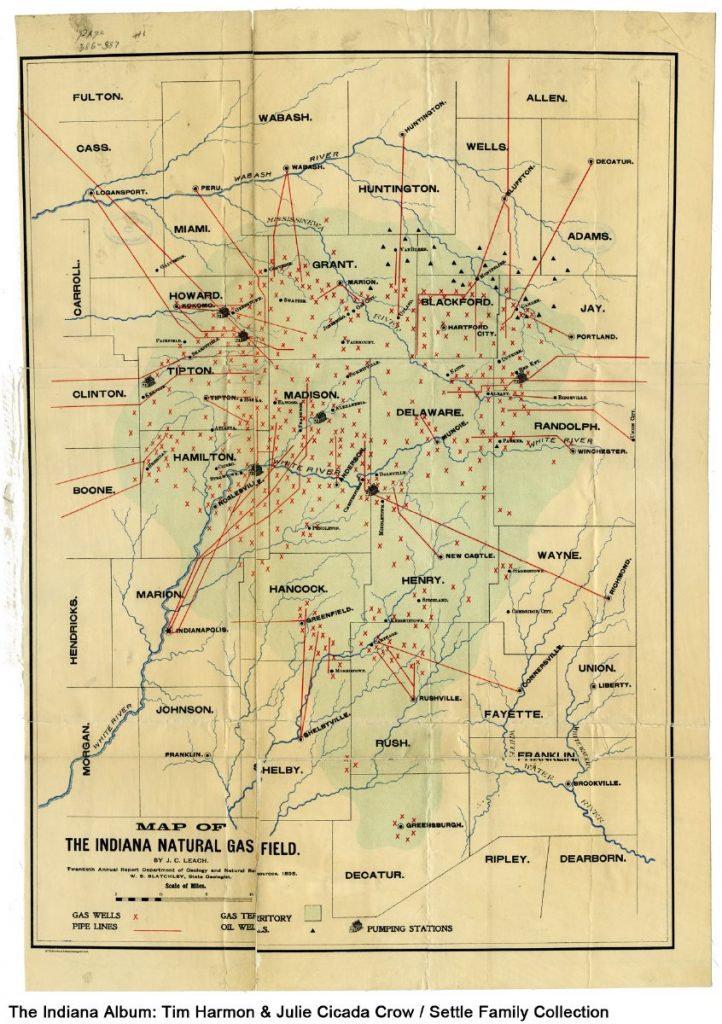

Discovery of an enormous natural gas field near Muncie in 1886 shifted the focus of Indiana gas companies from manufacture to distribution. IGL&C promptly organized the Indianapolis Natural Gas Company and began laying pipelines to the city. In early 1887, public dissatisfaction with IGL&C’s past service gave rise to the idea of a consumer-oriented gas company organized as a public trust.

Many in the community rallied to the new utility, purchasing enough stock from its promoters to enable Consumers Gas Trust Company to begin operation in 1888. In 1890, IGL&C and Indianapolis Natural Gas Company merged to form the Indianapolis Gas Company (IGC), which, in competition with Consumers, served the city for over a decade.

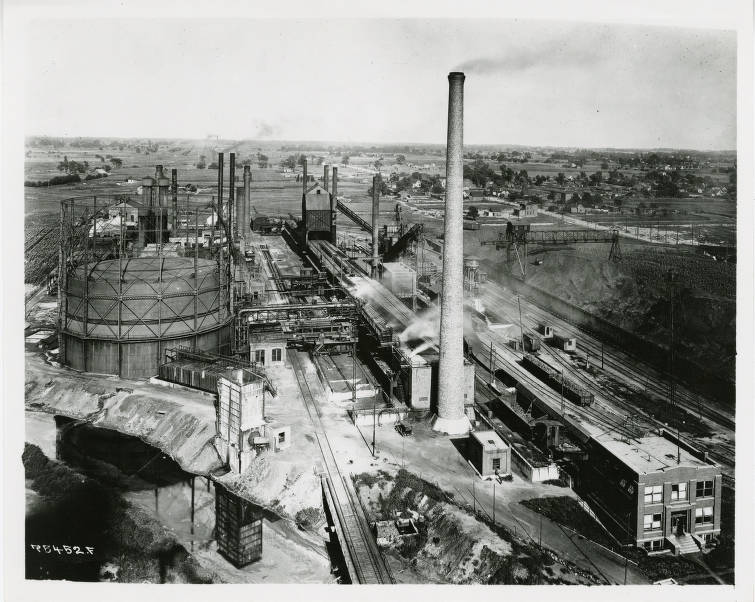

By 1902, the gas field was nearly dry, prematurely depleted by widespread waste, and customer rolls shrank drastically as the public resumed burning wood and coal. Its product gone, Consumers Trust fought a lengthy court battle for the right to reorganize as an artificial gas producer. The trust won its case in 1906 and was incorporated as Citizens Gas Company (not to be confused with the ill-fated Citizens Gas Light & Coke Company). By 1909, its new, state-of-the-art Prospect Street plant was operational and the company began to prosper, becoming strong enough to weather the changes wrought by creation of the state’s Public Service Commission in 1913. The less lucky IGC ended its independent existence that year and merged with Citizens Gas.

Over the years, the strategy of Citizens Gas has been to pay for gas production by selling coke and other by-products, but market fluctuations have frequently caused operating losses—a situation partly remedied by aggressive promotion of gas appliances. Unstable profits, combined with rising natural gas prices, consumer resistance to rate increases, and demands for expanded service have made the utility’s existence a strenuous one. Renamed Citizens Gas & Coke Utility (see ) after coming under municipal trusteeship in 1935, the company moved its offices to a new location at 2020 North Meridian Street in 1956.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, Citizens Gas & Coke Utility focused on its gas storage field in Greene County while also increasing its production of coke. By the 2000s, the company expanded, acquiring a steam plant from Indianapolis Power & Light (see ) as well as the Westfield Gas system. After closing the Prospect plant in 2007, the utility changed its name to Citizens Energy Group and continued expanding its services by acquiring Indianapolis’ water and wastewater utilities.

Electricity

Electricity first came to Indianapolis in 1882 when the Indianapolis Brush Electric Light and Power Company demonstrated this lighting innovation at the railroad depot on South Illinois Street. By contrast with oil and gas lamps, the newly developed carbon arc lighting used electric current to produce a safe, clean light of unprecedented brilliance. By 1892, the streets of Indianapolis and West Indianapolis were artificially brightened by the Brush Electric and Jenney Electric companies.

Indoor lighting, however, continued to be provided by gas and coal oil lamps until Thomas Edison’s demonstration of incandescent lighting in 1882 manifested its superiority over petroleum-based competitors. First used in Indianapolis on Thanksgiving Day 1888, “Edison service” quickly proved an effective source of illumination for both interior and exterior spaces. It could also be used for heating, as could the steam its plant boilers produced.

Electricity generated a great deal of entrepreneurial activity, and between 1892 and 1912, ten electric utilities were organized in Indianapolis. By 1927, only two survived with each serving half the area of the city. Their consolidation that year by a large out-of-state holding company created the Indianapolis Power and Light Company (IPALCO or IPL).

The new company merged its predecessors’ electric and heating systems, established a new operating center near Morris Street and Kentucky Avenue, and opened administrative headquarters at 48 Monument Circle. IPL soon pioneered the combination of electric service and high-pressure steam for industrial power, leading to steam sales second only to New York City’s.

At the time of the merger, IPL’s existing power plants were well able to serve its customers, but as Its numbers continued to grow rapidly the need for greater generating capacity became apparent. The Harding Street plant, begun in 1929, was a “super-power” plant whose high capacity and efficiency enabled local industries to set military production records during World War II and to meet the demand for electricity of a population swollen by an influx of war workers.

After the war, the demand for electricity soared due to population growth, suburbanization, and the increasing use of electric appliances, furnaces, and air conditioning. IPL responded with new power plants and equipment. At the end of 1991, the company was serving 390,000 customers in Marion County and had a system generating capability of 2,829 megawatts.

IPL was acquired in 2001 by AES, a global power company. Through the early 2000s, IPL began purchasing energy from Indiana wind and solar farms. They built The Advancion Energy Storage Array, a battery-based energy storage system and ceased coal use in two stations. In 2019, plans were laid to retire even more coal-firing units.

Telecommunication

The telephone made its debut in Indianapolis in 1877, two years after its invention, when the city council allowed a local coal dealer to run a telephone wire between the company office and its coal yard.

In 1878, the usefulness of the still rudimentary invention increased dramatically when the first workable exchange was developed. This made possible switched calls among any number of subscribers rather than direct connections between only two or three parties. Entrepreneurs promptly established an exchange in Indianapolis, but it failed to attract enough customers to survive. The following year Ezra Gilliland, one of these entrepreneurs who also owned a small electric shop, became licensed manufacturer of Bell Telephone Company equipment in the United States.

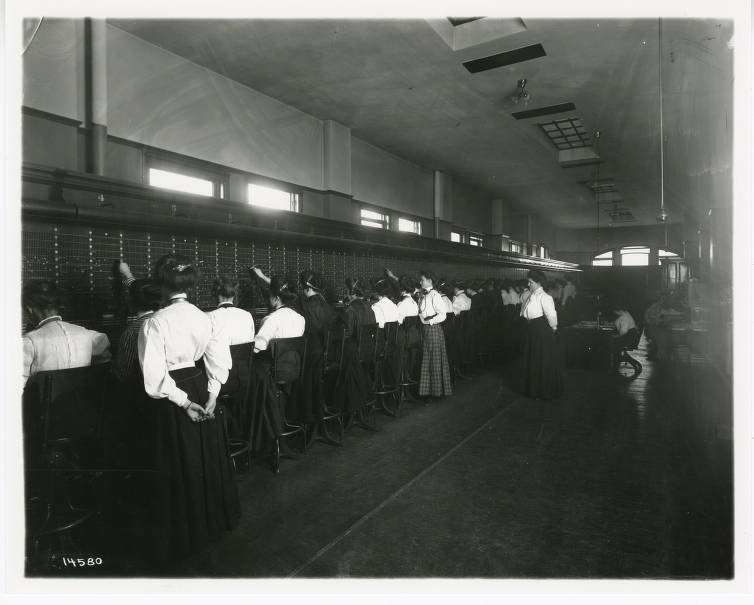

By 1883, Indianapolis had enough telephone users to justify the publication of its first directory and like many other cities was served simultaneously by multiple telephone companies. The intense competition kept rates low but was otherwise inconvenient because the systems were not interconnected. By 1906, only two telephone companies remained: an American Bell licensee, Central Union Telephone Company, and an independent, New Telephone Company. Each had about 10,000 customers with several thousand duplications. Central was later dissolved after a reorganization in American Telephone and Telegraph, of which it had become a subsidiary. In 1916, New Telephone and the expansion companies to which it had given rise were merged to create the Indianapolis Telephone Company.

During World War I, the federal government took control of telephone and telegraph communications under the postmaster general, who ordered the consolidation of local companies nationwide. As a result, Indianapolis Telephone Company was purchased by the Bell System in 1918. was organized in 1920 and by the end of the year was operating 65,000 telephones in the city.

The number of telephone subscriptions has steadily increased since that time, accompanied by improvements in equipment and service. In 1949, Indianapolis recently converted to an all-dial city, celebrated the installation of its 200,000th telephone. Three years later Indiana Bell adopted a two-letter, five-digit telephone numbering system to accommodate its expanding customer base.

During the next decade, touch-tone telephones and all-digit telephone numbers were introduced, direct dialing replaced operator-assisted long-distance calls, and the city’s local calling area was expanded to cover many communities in the surrounding counties.

Indiana Bell was divested in January 1984, becoming part of Ameritech, a Regional Bell Operating Company. By 1993, Ameritech dropped the Indiana Bell name and replaced it with Ameritech Indiana. SBC Communication acquired Ameritech in 1999 as well as AT&T Corporation in 2005 and changed its name to AT&T Inc. In September 2016, the increase in telephone usage required a 10-digit number for all local calls.

Water Supply

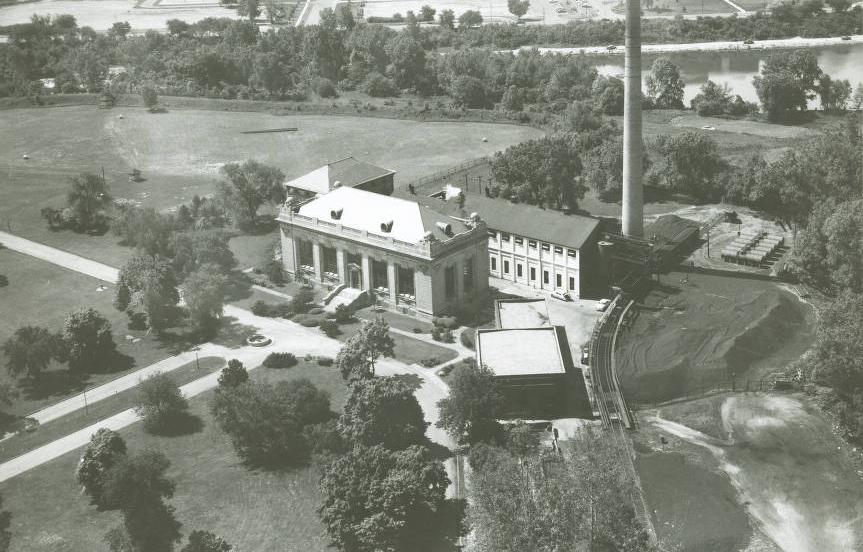

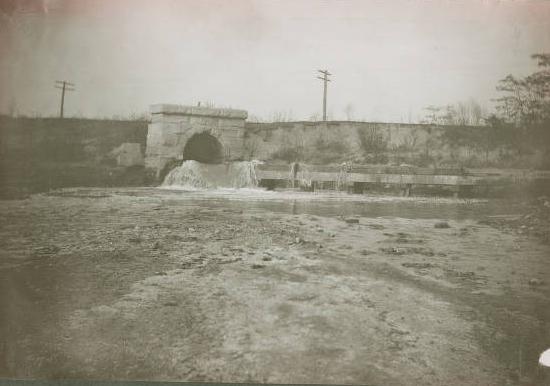

Well water was safe for the tiny population of early Indianapolis but had become dangerously contaminated for the 18,000 people living there in 1860. The city had no water system until 1871 when James Woodruff’s Water Works Company (WWC) dug wells, built the city’s first pumping station nearby (the present headquarters of the White River State Park Commission), and began laying mains. WWC soon found, however, that few people were willing or, after the Panic of 1873, able to pay for piped water.

In spite of poor water quality, low water pressure that hampered firefighting, and a small customer base, WWC managed to stay in business until 1881 when its assets were purchased by the newly organized (IWC).

IWC gradually began to improve service. In 1889, it built a second pumping station (Riverside) to raise pressure and dug deep wells to improve water quality, but there was simply not enough water underground to supply the city. In 1904, newly constructed slow sand filtration beds began purifying water from , making Indianapolis one of the first large American cities to treat its water supply.

During the next three decades, IWC expanded the water system by building the Fall Creek pumping station, converting to a metered system, adopting improved purification techniques, and constructing raised water tanks to maintain pressure at higher elevations where the city’s new suburbs were being developed.

Growth continued during World War II as IWC added a filter plant to Fall Creek Station and completed —a seven-billion-gallon impounding reservoir. In 1948, IWC construction doubled the capacity of the Fall Creek filtration plant, which purified water for the city’s northeast side.

All other parts of Indianapolis drank purified White River water from either the or pumps near the river. In 1955, the company-built —named for Howard Morse, the IWC president who had planned it—on Cicero Creek. The Eagle Creek water filter and pumping station was added in 1973 to serve northwest Marion County.

Through the 1990s, the company maintained eight pumping stations to distribute water to over 200,000 city customers through more than 2,500 miles of water mains. In 2002, the city of Indianapolis purchased Indianapolis Water Company, changing the name to Indianapolis Water. Poor management and Indianapolis’ declining water utility infrastructure prompted the city to sell Indianapolis Water in 2011 to Citizens Energy Group.

Sewer System

Early Indianapolis was drained by culverts and above-ground wooden gutters that haphazardly carried wastewater and sewage to the White River. The city was in need of an underground sewer system but delayed due to the cost. By the 1860s, the growing city’s inhabitants began to demand clean streets and the elimination of the odors that marred Indianapolis’ burgeoning prosperity.

In 1870, the city began constructing a sewer system, but it was never fully completed. Nearly 20 years later, when the made a thorough study of the city’s sewerage, it found the old system in a state of collapse, dumping sewage into all watercourses within the city limits and frequently causing many streets to be flooded with sewage and wastewater. Elected officials ignored the club’s recommendations for a new, adequate sewer system because it would require raising taxes.

By 1909, the unabated pollution of White River caused communities along its banks to seek court injunctions against upstream towns for dumping raw sewage into its waters. Indianapolis needed a sewage treatment plant, but prior to 1915 municipalities could not legally incur the level of indebtedness required for so expensive an operation. That year the state legislature enacted a bill enabling cities to establish sanitary districts separate from the municipal corporations with the authority to issue bonds to finance infrastructure development.

By 1925, the Belmont sewage disposal plant began operation on the city’s southwest side. It was the first large activated sludge water treatment plant in the United States. The city added a second facility in 1966, the Southport Treatment Plant, to accommodate further growth. By 1981, the southside plants were updated and expanded to meet both continued urban growth as well as state and national mandates to further improve the White River’s water quality.

Meanwhile, the city’s combined storm and wastewater sewer system was no longer adequate, leading to sewage overflow during heavy rainfall. When Citizens Energy Group acquired Indianapolis’ water utilities in 2011, they began working on the tunnel system. This 28-mile network of large tunnels was constructed to help reduce sewage overflow into waterways by storing over 250 million gallons of sewage, which slowly releases to a wastewater treatment plant.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.