In the early 19th century, the demand for printed information in new Indiana settlements often led to the establishment of printing offices; Indianapolis was no exception. Besides job work (billheads, broadsides, cards, posters, and the like), which was the fledgling companies’ “bread-and-butter,” newspapers represented the most significant printing and publishing activity. Few newspapers before 1860 had more than 1,000 subscribers, and most had half that number or fewer.

The first newspaper in Indianapolis was the , appearing on January 28, 1822, and published by George Smith and . This and subsequent early newspapers were typically four pages with three or four columns to the page. They were printed on hand presses using paper imported from eastern suppliers. Bolton later recalled that he applied ink to the locked forms of composed type using ink balls made of dressed deerskin stuffed with wool. He kept them soft with raccoon oil when not in use.

Subsequent names of the , which often also signaled a change in ownership, were the (October 22, 1829), the (April 14, 1830), the (August 14, 1830), the (August 21, 1840), and the (July 21, 1841), which finally expired on February 26, 1906.

For other long-lived Indianapolis newspapers, similar changes in ownership, periodicity, and name were the rule, not the exception. Other important Indianapolis newspapers included the (March 7, 1823), later the (January 11, 1825), and the (about 1844), which merged with the on June 8, 1904; the (December 7, 1869), which was one of the two newspapers by 1994 being published as part of Indianapolis Newspapers, Inc.

The (September 3, 1895), which became the on May 20, 1903, and later the (April 14, 1913); and the (June 6, 1903), which was sold to in April, 1944, and by 1994 was the second newspaper published by Indianapolis Newspapers, Inc.

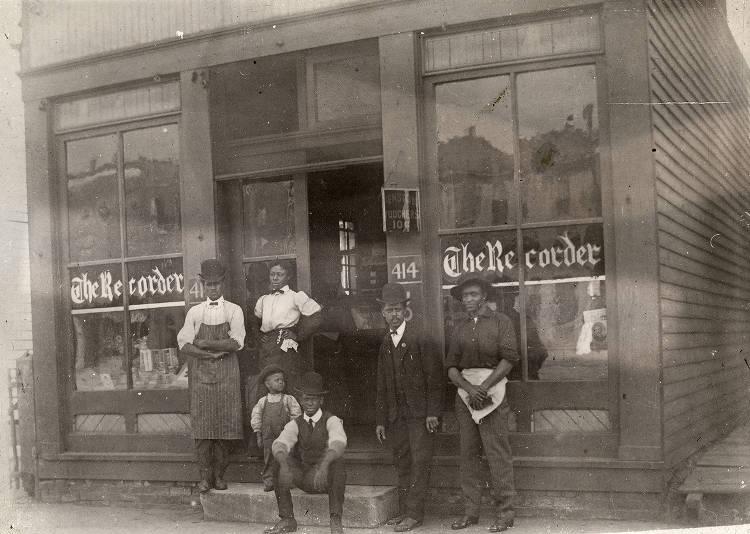

Indianapolis had witnessed the publication of at least 185 different newspapers through 1980, many for only an issue or two. Some of longer duration include school newspapers (the [ca. 1885] and the [1898] from Shortridge High School); German-language newspapers ( [September, 1848], which later became the [April, 1875], the [March, 1907], which ceased publication in early June 1918, and the [September, 1853-1866]); and African American newspapers ( [1949-1957], which became the , and the [1896]).

Early book publishing in Indianapolis took place in newspaper offices. The first book was probably , and , written anonymously by and the clerk of the Marion County Circuit Court and published by Smith and Bolton in 1822. Since literature was more easily imported from eastern publishers via Cincinnati dealers, the subsequent subject matter of local productions was usually official. Minutes and proceedings of meetings, speeches, reports, sermons, college catalogs, and city directories were the most common imprints. More substantial histories, music, maps, and textbooks, however, began to appear by midcentury.

After the Civil War, an increase in the number of settled communities in Indiana without bookstores prompted a significant rise in subscription book publishing in Indianapolis. Firms such as Fred L. Horton & Company on East Market Street, and Beckworth & Waite, 42 Vance Block, acted as surrogates for outstate publishers such as Henry Howe of Cincinnati, and the American Publishing Company of Hartford, Connecticut, and they might best be described as book distributors.

At midcentury, many Indianapolis newspaper printers published the occasional book. Relying on paper and type supplied from outside Indiana, including the Franklin Type and Stereotype Foundry in Cincinnati, these firms included Cameron & McNeely, whose Capitol Steam Printing Office also published the ; the Indiana State Journal Steam Printing Establishment; and the Indiana State Sentinel Steam Printing House. City directories were the stock in trade for Henry N. McEvoy (whose city directories were printed at the Sentinel office), A. C. Howard, and others, whose efforts were largely replaced in 1878 by R. L. Polk & Company.

Indianapolis has had its share of non-newspaper printers and/or publishers since the mid-19th century; three firms, however, stand out. The evolved out of a partnership between Miles Burford and William Braden in the 1860s. Miles’ son, William, took over the business in 1875 and built it into one of the largest and most successful printing concerns in Indiana. Burford served as the state printer for many years, and for three decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries handled all printing incident to sessions of the General Assembly.

John Carlon and C. E. Hollenbeck founded the printing firm of Carlon & Hollenbeck, later , in 1867. Located on the southeast corner of the Circle at Meridian Street, Hollenbeck came as close to fitting the definition of a “fine printer” as any operating in Indianapolis in the late 19th century. The firm’s advertising proclaimed its interest in the “unseen specification,” which “stood for the addition of higher characteristics to printed things,” where ink, paper, and metal were not the end products but merely “the instruments through which our real product is expressed.”

Begun in 1838 as Merrill & Company, a book and stationery store owned by E. H. Hood and , the publishing firm of was a happy exception to a 19th-century publishing rule—a successful, long-lived trade publisher located outside the eastern publishing centers of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. The firm changed its name several times: Merrill, Meigs & Company after the Civil War; the Bowen-Merrill Company in 1884, when it merged with Bowen, Stewart & Company; and finally the Bobbs-Merrill Company in 1903. Volume 5 of the (state Supreme Court decisions) was the firm’s first publication. In 1899 it amplified its interest in legal publishing by purchasing the law book list of Houghton Mifflin, and 13 years later it purchased the right to publish 125 titles in law from the American Publishers Company of Norwalk, Ohio.

The firm published many Indiana authors. ‘s first collection of poetry,” (1883) and ‘s (1891) found notable success through their association with Bobbs-Merrill. The firm’s greatest success began in the early 20th century when it issued books of national interest such as (1898) by Charles Major; L. Frank Baum’s (1900); and Mary Roberts Rinehart’s (1908). Bobbs-Merrill also supported psychology and other emerging social sciences with multivolume series such as The Childhood and Youth Series.

Bobbs-Merrill remained a major publishing firm until its demise, and its list included the phenomenal bestseller, (1931, and subsequent editions). In its later years the firm discontinued its wholesale paper and retail bookselling departments and focused on the publication of trade, law and schoolbooks.

After about 1970 numerous offset lithographic printers (the so-called “quick” or “instant” printers) appeared, and Indianapolis had no shortage of such firms. Several, however, offered many additional services, such as design and color printing. Among these were Shepard Poorman Communications Corporation, noted also for its full-color calendars; Alexander’s Standard Printing; Design Printing Company; and White Arts.

By 1994 Indianapolis had regional offices and distribution centers for several national publishers headquartered elsewhere in the country. Indianapolis publishing itself had taken on a regional or specialist aura. Hackett Publishing Company, founded in 1972, specialized in college textbooks and scholarly books. Que Corporation, a division of Macmillan Computer Publishing, rode the wave associated with the rise of the personal computer and the consequent demand for books to explain software documentation. And the Guild Press of Indiana, founded in 1987, specialized in books about Indiana and the Midwest.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.