The push for public playgrounds and swimming facilities in Indianapolis was part of the national progressive movement to save urban children. As early as the 1880s, national and local reformers believed that supervised play and recreation helped build character and citizenship in children and protected them from playing in dangerous city streets.

In Indianapolis, the development of pools and playgrounds was originally a private effort. In 1905, the Children’s Aid Society started the first supervised bathing program at the Taylor Bathhouse at Fall Creek and Senate Avenue. The society opened the Schissel Bathhouse at West Street and Central Canal near in 1907. The support and interest of the Indiana Federation of Women’s Clubs helped to garner special appropriations from the city so that five additional free bathhouses opened along Fall Creek and White River in 1911.

These groups pushed for the passage of the original state playground law in 1913, which allowed local municipalities to set up playgrounds. Indianapolis had already committed police to patrol non-swimming areas and was operating six bathing places and nine playgrounds. The following year, 1914, the sponsored a study of recreational conditions and needs, hiring an agent of the National Playground Association of America (NPAA) to conduct the study.

As a result of recommendations to expand facilities and supervised programming, the following year there were 7 bathing beaches, 3 swimming pools, 10 school grounds maintained by the city, 12 swimming holes and bathhouses, and 28 playgrounds in operation. Critics argued that such expenditure on public recreation was wasteful. Momentum for playgrounds continued, however, so that in 1916 the Indiana University Extension Division, along with the NPAA, sponsored a statewide recreation conference in Indianapolis. The extension division then established a training program for playground leaders administered by Dr. Henry Curtis, who had experience in establishing playgrounds in other cities.

By 1920, the recreation division of the Indianapolis Park Board had assumed much of the responsibility for pools and playgrounds. Under R. Walter Jarvis, the park board operated 40 playgrounds, arranged according to a survey of the population to serve children within a half-mile radius of their homes. The park board also took over the training of playground leaders and lifeguards. The playground law in 1925 legalized this arrangement. Two years later, another state law allowed cities to collect taxes for local recreation.

By 1930, many people believed that there was no more room for additional playgrounds in Indianapolis, yet a 1929 recreational survey, sponsored by the Indianapolis Council of Social Agencies and conducted by the NPAA, called for more and better playgrounds and further cooperation with schools. The council study was virtually the last act of the “playground movement” in Indianapolis, with the municipal Park Board assuming total control thereafter.

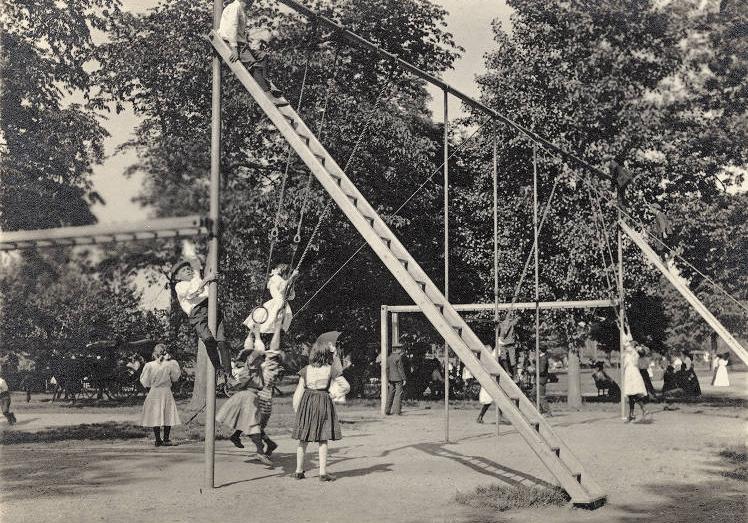

Throughout these formative years, pools and playgrounds were open and supervised six days a week, eight hours a day. The standard playground equipment included swings, slides, sandboxes, maypoles, merry-go-rounds, seesaws, and athletic fields. Equipment like this was readily available nearby in , Indiana, home to the first manufacturer of such playground equipment in the United States—American Playground Device Company, which was founded in 1911. In addition to providing playground equipment, play leaders at Indianapolis parks also organized sports, such as baseball leagues for both boys and girls, and conducted structured activities including weekly storytelling, sand-pile contests, sewing for girls, crafts, swim lessons, and pageants.

The playground and pool movement helped provide many Indianapolis children with a place for safe recreation. It did not, however, provide for Black children or families in the same way. While there were segregated playgrounds, they were not well equipped or supervised. None of the pools were open for use to Indianapolis’ Black citizens until 1924 with the opening of the Douglass Park pool. This single pool was all that was provided for the over 70,000 African Americans living in Indianapolis until the late 1950s.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in public facilities. However, white flight and reduction in the tax base in Marion County have resulted in some continued inequities in programming and maintenance in the city park system.

By 2020, there were 125 playgrounds, 19 aquatic centers, and 21 spray grounds in operation in Indianapolis.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.