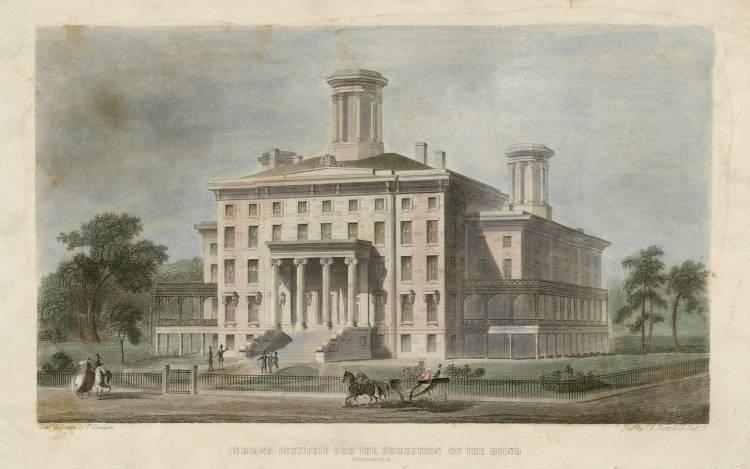

Leaders of Indianapolis’ business community have been actively involved in charitable and philanthropic endeavors since the city’s founding. Early leaders, like , , and , came from the northeastern United States, bringing with them concepts of social responsibility and community stewardship. They assumed leadership roles in politics, benevolent societies, religious institutions, and economic and community development. Civic leaders organized the 1840s Irish famine relief efforts, established the , and helped create the city’s public school system and schools for the blind and deaf. These individuals demonstrated their commitment to the community and its citizens and established a philanthropic precedent for future generations of business leaders. The business sector continues to provide leadership and financial support to nonprofits to this day.

Numerous voluntary associations originated during the 1890s, which allowed the business community to define by example what it meant to be a “good” business and a responsible citizen in Indianapolis. Among them was the Commercial Club founded in 1890 by 27 prominent businessmen. modeled strong convictions about the obligation of businessmen to be responsible to and for the community where they resided. Lilly practiced a “stewardship of wealth,” which held that it was appropriate and wise to use a portion of personal (and business) income for community improvement. Social settlements were among the new nonprofits at the turn of the century. Indianapolis settlement workers, unlike those in other cities, sought to help their clients adapt to the industrializing economy, rather than to lobby to change it. The Indianapolis settlements all formed pragmatic alliances with business leaders.

Men’s public lives naturally centered around business, so many early Indianapolis voluntary associations were business-related, such as the , Bar Association, State Medical Society, and Indiana Manufacturers’ Association. New clubs built upon business connections but did not have to be professional associations, such as the Century Club, , and Indianapolis Country Club. During the City Beautiful movement, businessmen as civic “boosters” promoted Indianapolis through physical and institutional improvements. Businessmen’s civic clubs were founded partly in response to City Beautiful: Rotary in 1905, in 1915, and Lions In 1917.

The business community developed informal criteria for philanthropic contributions. First, there must be an emphasis on good financial planning with a sound monetary base. Second, the project should include economic advancement and a well-conceived promotion of the city. Third, effective management and leadership should be identified and charged to get results and not seek personal credit for accomplishments. Such factors remain primary considerations for business participation today.

Philanthropy and business became stronger partners during the 1920s, a period of civic growth and improvement. Personal and voluntary spirit, as well as financial contributions, enhanced the quality of life locally. Author captured that sense in 1920 when he wrote, “The continuing charm of Indianapolis lies in the sturdy Americanism and broad democracy of its founders. A certain folksiness and neighborliness of pioneer life retained is the secret of the real Indianapolis atmosphere.”

The Commercial Club and five other business organizations (Adscript Club, Freight Bureau, Indianapolis Trade Association, Manufacturers Association, and Merchants Association) merged in 1912 to form the . The Chamber has remained active in bridging business, philanthropy, and government.

The Cleveland Chamber of Commerce had pioneered the foray into welfare work when they created a Committee on Benevolent Organizations to evaluate, regulate, and streamline charity work. The committee eliminated fraudulent charities, consolidated data, coordinated fundraising, analyzed donors, and provided management oversight. When became president of the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce, he followed the Cleveland model. The Chamber of Commerce became the lynchpin organization that connected the three sectors, and men who were prominent in one arena were often influential in the other two.

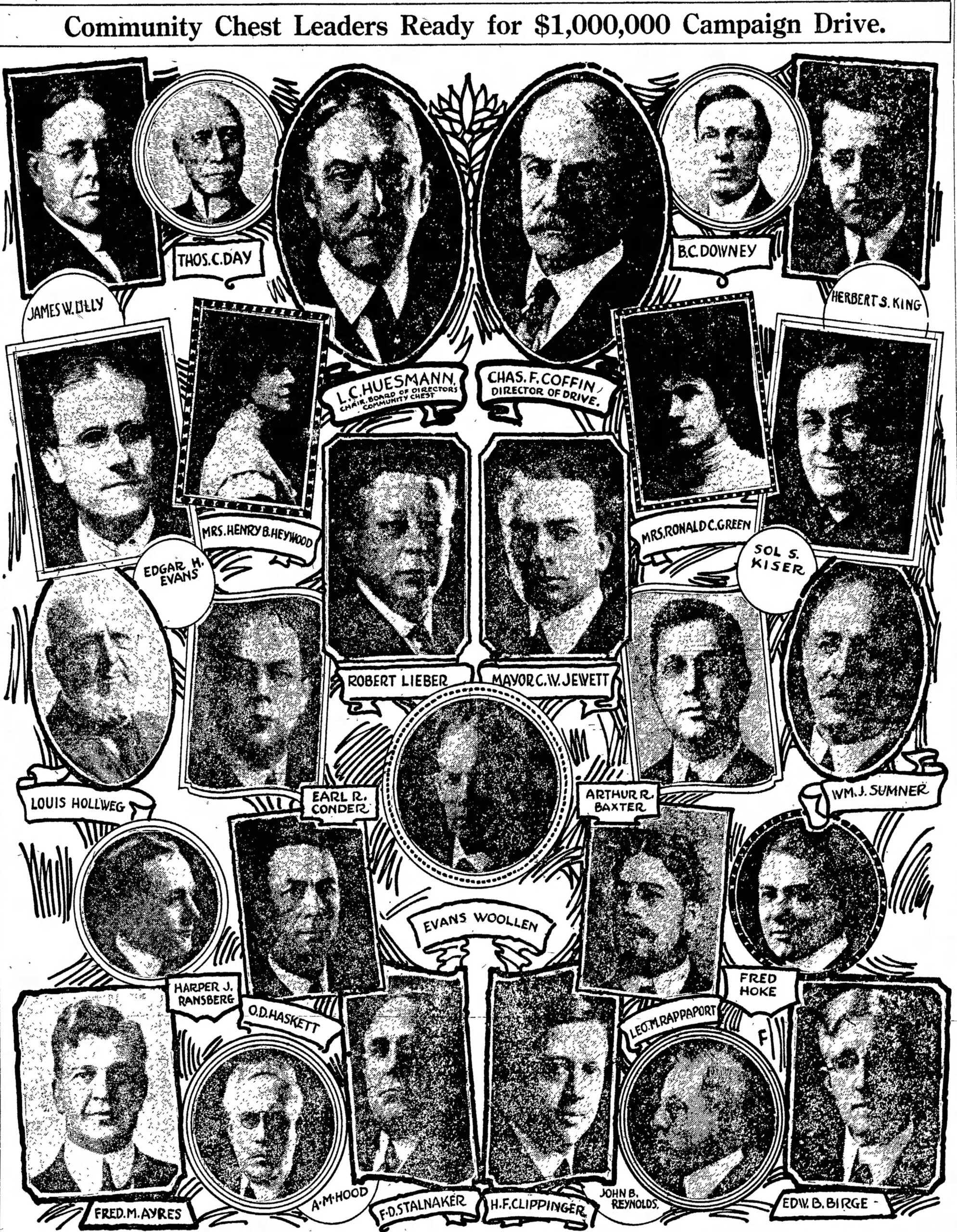

The advent of centralized fundraising via the community chest () brought business and charity leaders into even closer association, allowing community leaders to readily grasp social problems and integrated solutions. One testimonial described the chest as showing that “human welfare is one big problem rather than a series of unrelated small ones.” The chest structure solidified businessmen’s power over charities’ annual operating budgets. Likewise, in a 1926 advertisement, an anonymous businessman called for business and citizens to “work together—for Indianapolis first, last, and always.”

One of the early cooperative efforts to promote the city and the use of the automobile was the Citizens’ Speedway Committee, established by the Chamber in 1920 to raise funds for the . The committee remains active as one of the organizations, most of which are led by business volunteers.

Despite the seriousness of the , many local business leaders sustained their philanthropic contributions over the years. Work relief committees focused on a system of public works. lent 70 acres of land to promote efficient home food production. Chamber of Commerce leaders looked to solve the problems of adequate housing for workers and the unemployed. In 1934 they also organized a successful campaign, led by corporate executives and supported by corporate donations, to save the from collapse.

In the early 1950s, local business leaders confronted the critical need for hospital beds and services through a $25 million hospital development campaign over 10 years. The latter half of the 20th century brought significant changes for Indianapolis, many of which resulted from the commitment of human and financial resources from business.

Under mayors John J. Barton, , , and , government and business leaders adopted a strategic plan that required cooperation and collaboration at new levels. The phrase “public/private partnership” became the community’s byline and elevated the nation’s awareness of Indianapolis. Subsequent mayors , , and have continued this approach.

Business and philanthropy developed different mechanisms for working more closely. They created several community-based nonprofit organizations to serve and promote the community’s development, including: the (GIPC), the Indianapolis Economic Development Corporation (IEDC), (IDI), the (ICVA), the (IP), the , (CLASS), and the (CCC). The majority of board members and operating funds come from the business community.

In 1985 the Chamber of Commerce established the 2 percent–5 percent Club to recognize businesses that donated at least 2 percent of pretax profits to community organizations, philanthropic projects, or other civic causes. Unlike similar clubs in other cities, the local club continues to grow although members receive no public recognition. Businesses provide extensive leadership for the United Way of Central Indiana, the , the , and the network of human service providers.

Philanthropy, business, and government continue to partner in developing and delivering the assistance of many types to the underserved and underrepresented in society.

Indianapolis businesses and labor organizations also have contributed generously with in-kind donations. Volunteers annually transform the into the “World’s Largest Christmas Tree.” Small businesses actively participate by giving time and career guidance through educational programs like Partners in Education, Junior Achievement, and the Center for Leadership Development.

Business leaders and corporations today support philanthropy through individual and corporate donations, corporate matching grant programs, employee volunteer programs, corporate sponsorships, and business leaders lending expertise through trusteeship of nonprofits. Another strategy is the corporate foundation, popular since the 1950s. Corporate foundations receive allocations from corporate profits for subsequent donations to charities. The structure allows corporations to make tax-deductible contributions to their foundations when profits are available and even out charitable donations over time. Although corporate giving represents only approximately 5 percent of total donations to the nonprofit sector, business has unquestionably supported philanthropy over time.

The Foundation Center indicates approximately 100 foundations domiciled in Indianapolis that make grants in the Indianapolis area. Several have spent down or are inactive, but most of the foundations in this list are the result of corporate or founders’ investments , , , , the , and the , conversions ( and ), or founder’s investments affiliated with the ( and ).

Corporate underwriting of nonprofit organizations is increasingly linked to marketing and increasingly requires a link to a business return. Nonprofits’ increasingly commercial behavior is evident in collaboration with for-profit enterprises. The cause-related marketing movement has created many alliances between the two sectors, such as for-profit corporate advertising and naming-rights contracts.

Corporate giving, however, has been challenged in the last few decades. Corporations have merged and downsized, reducing their presence in local communities. Globalization has changed the complexion of many industries and decentralized employment throughout the world. Indianapolis has lost corporate headquarters and manufacturing has shifted out of the state, which has diminished the city’s financial resources. Many large businesses are down-sized and many are no longer locally, state, or even nationally domiciled. New businesses in the biotech and technology industries have established headquarters or substantial operations in Indianapolis, which may continue the important business and philanthropy partnerships in the future.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.