Photo info …

Credit: Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library View Source

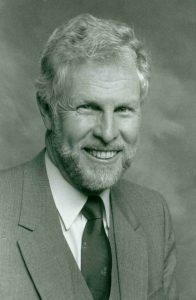

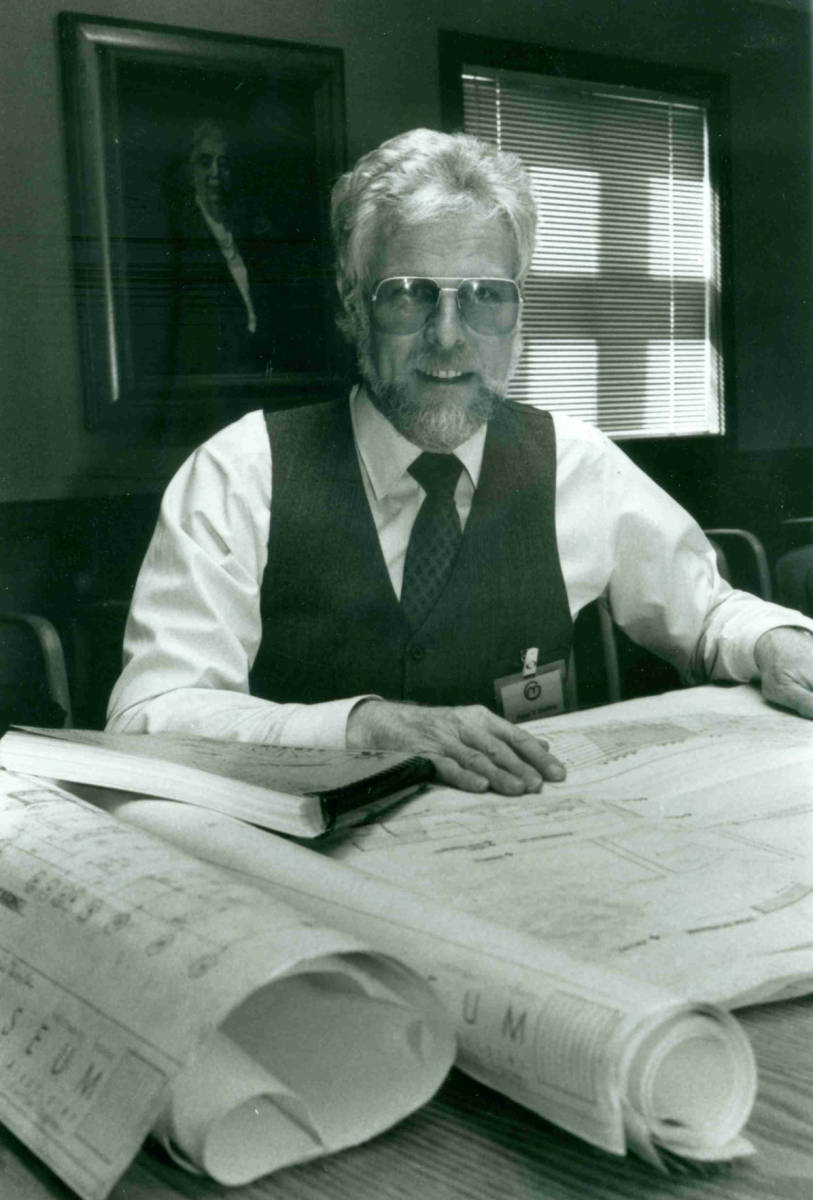

(July 9, 1935 – Aug. 30, 2016). Peter Sterling was president of the from 1982 to 1999. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he was the son of Clarence Irving and Edith Van Orden Sterling. He graduated with degrees in history from Davidson College in North Carolina and completed studies at Georgetown University in Washington, D. C.

Sterling had formerly chaired the history department of the New Hampton School, in New Hampshire; directed Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s education and group visits program, and was executive director of the U.S.S. Constitution Museum Foundation in Charlestown, Massachusetts. When recruited to the Indianapolis museum, the life-long East Coaster eagerly jumped at the opportunity to move to the Midwest. “When the chance came along to head to what I knew was one of the best museums in the country, I went for it,” he told in March 1984.

Endlessly curious about the world, Sterling believed strongly in the positive impact nurturing adults could have on children’s lives. “We don’t want to be known as a museum for children; we want to be a museum with children” was his mantra, which resulted in dramatically different types of exhibits and programs at the museum.

Involving children in the planning and design process meant that museum staff roles changed from being “the experts” to becoming facilitators, teachers, and mentors. Exhibits changed from didactic presentations to engaging explorations that encouraged young people to think and ask questions, develop hypotheses, solve problems – and have fun in the process. Rather than “hands-on,” as most children’s museums describe themselves, the Indianapolis museum became known nationally and internationally for being “minds on.”

This unique approach led to significant physical growth for the museum, including the Welcome Center, SpaceQuest Planetarium, Cinedome Theater (later the Dinosphere), and the Eli Lilly Center for Exploration (CFX). Other museum assets grew as well during his tenure. While most children’s museums have no collections, the Indianapolis museum doubled its assemblage of artifacts in 1984 with the donation of the Caplan collection, 50,000 folk toys from 120 countries. In 1997, a $40.4 million bequest from Enid Goodrich, the wife of founder Pierre F. Goodrich, became the largest donation the museum had ever received.

The focus on nurturing young people’s interests also led to program expansion, often in partnership with others. The museum and the launched the in 1984 to recognize outstanding artistic achievement in high school students. A statewide lending library (later a branch of the ) opened in 1992. Children’s Express (later ), a youth journalism program, opened a bureau at the museum in 1990. And the Museum Apprentice Program, a homegrown program, attracted hundreds of youth from central Indiana who were mentored in how to teach with objects and interact with adults and children, and then offered opportunities to practice their new knowledge and skills with visitors.

Sterling’s belief in mentoring younger people extended to his staff. Other museums noticed and came calling, recruiting many of the museum field’s next generation of leadership from people who learned their craft at The Children’s Museum.

Farther afield, the museum developed program partnerships with cultural institutions in Canada, Japan, Russia, and Sweden and introduced indigenous South American artisans to the Midwest during 1987’s . But as the museum’s reputation grew outside Indianapolis, Sterling also ensured the museum remained a safe and welcoming place for the children and families who lived in its immediate neighborhood.

Sterling moved to Waynesville, North Carolina, in his retirement and continued his work as a member of the Waynesville Historic Preservation Commission. He developed The Haywood Snapshot Project “to preserve and share historical photographs” for the organization.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.