The neighborhood colloquially known as Midtown is a historically African American neighborhood bounded by 16th Street, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, Ohio Street, and the , although some planners have placed the original border somewhere around historic Agnes Street (now known as University Boulevard). Black residents settled in this area, then known as “Bucktown,” before the Civil War. By 1870, these individuals had erected two churches in the district, and , which bisected the area, had become the core of the local African American community. Jones Tabernacle AME Church was formed in the area in 1872, and its members constructed a building at the corner of Michigan and Blackford Streets in 1882. The church was important to the community and became one of the largest congregations in the city. Residences bordered the streets with one- and two-story frame homes in styles ranging from shotgun to foursquare.

The growth of Indianapolis’ Black population mirrored the rise of Bucktown. Over the course of the 1870s, the Indianapolis Black population swelled by 122 percent to more than 6,000 residents, fueled by post-Civil War migration out of the South. Many of these individuals settled on the city’s near-westside in neighborhoods like Bucktown. For instance, in 1880, the federal census for the Indiana Avenue area identified 115 of the area’s 682 residents as Black or Mulatto, and 48 of those 115 were from Kentucky (more than from any other state).

From 1880 to 1920, the city’s overall population increased quickly, and the Black population grew exponentially. The most significant growth came between 1890 and 1900. By 1900, the city’s population identified as Black or Mulatto had grown to nearly one-third of the city’s overall population (169,164 people total). This was reflected in the Bucktown/Indiana Avenue neighborhood. The 1920 federal census showed that 77 percent of the total Indiana Avenue population (801) identified as Black or Mulatto.

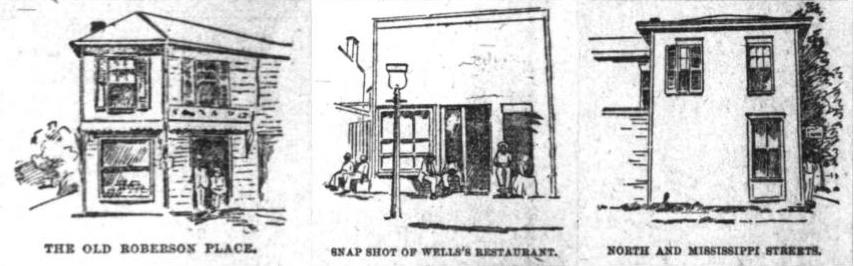

Consequently, Indiana Avenue had grown into an eight-block business district serving the Black residents of the area by the 1920s, with the most significant segregation in the area located in the street’s 800-900 blocks. In 1927, the opened at the corner of Indiana Avenue and West Street. The edifice housed professional offices, a drug store, a beauty shop and college, the Walker Casino and Theatre, and a restaurant, which offered employment and services?for Midtown residents.

In the same year that the Walker Building opened, so too did the Black, segregated , also within the neighborhood’s boundaries. The school, which opened as a segregated place to learn, would educate numerous famous individuals such as professional basketball player Oscar Robertson and U.S. Congresswoman .

As early as 1932, the Public Works Administration and the Advisory Committee on Housing of Indianapolis had plans to begin a segregated Black “slum clearance” and municipal housing project in Indianapolis, but it was not until May 1934 that a financially depressed part of the Midtown district was chosen. By the end of the year, most of the 363 residences that encompassed a 22-acre area bounded by Blake, North, and Locke Streets, were purchased and awaited demolition. Designed by Merritt Harrison and William Early Russ, the 24-building project built in their place consisted of low-income housing, playgrounds, and courtyards. It was one of the first federally funded housing projects in the U.S.

Opening in February 1938, the 748 units in Lockefield were filled by September of that year after community administrators received 1,700 applications for residence. Public School No. 24, the only original building left standing after the demolition, continued to serve the area as a neighborhood school.

While Lockefield Gardens became integral to Midtown’s social atmosphere, local officials fought the construction of the community (seeing it as a rejection of laissez-faire development) and resisted assuming the administration of the site. They also rejected the formation of the Indianapolis Housing Authority (IHA) until 1949, which would have administrated the complex, and, once established, they did not make use of the IHA’s power with any substance for at least another decade.

The neighborhood behind Crispus Attucks High School was known as Pat Ward’s Bottom. At the time that Lockefield was developed, it was an African American community tightly packed with small homes. Identified as “blighted” by the Indiana General Assembly in 1945, Pat’s Bottom was the neighborhood that the Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission chose for its first slum clearance initiative. Demolition of homes began there in 1948. To counter the dislocation of families in Pat’s Bottom, the African American social service agency, , extended an opportunity for Black residents to own homes in the area. By paying $300 down and working about 1,200 hours, they could earn equity in a house. The Flanner House Home initiative brought national attention to the agency and made it possible for some families to remain in the Midtown area.

Following World War II, Indiana Avenue became increasingly recognized for its jazz club scene, an extension of the Black expressive culture that had begun to develop there at the beginning of the 20th century. Well-known jazz musicians such as , , and many others played at neighborhood clubs.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the adjacent Lockefield Gardens fell into disrepair because of the disinterest of local officials and the IHA in its maintenance. By 1971, numerous residents began to move out of Lockefield. At this time, the city attempted a redevelopment program for the complex, while the physical space itself became the target of urban renewal advocates. As part of the Indianapolis Public Schools desegregation case, federal judge ruled that Lockefield could not be resettled as a Black-segregated neighborhood. He interpreted the city’s plan for the complex as a means of perpetuating residential and educational segregation. In 1976, following this ruling, residents were moved to other housing projects. Lockefield closed and was condemned.

Having long aspired to expand its medical campus, the Indiana University system targeted and subsequently purchased property in the Midtown neighborhood, moving east of the Indianapolis campus’ location and up to the land surrounding Lockefield Gardens during the mid-1960s. This process relied on the campus becoming tenants for each section of land purchased and then converting the property into grounds for the campus upon the Midtown residents’ departure from their homes.

From the 1960s and through to the 1980s, prosperous neighborhoods surrounding Indiana Avenue also depopulated. This loss of a once vibrant Black community persisted when a group consisting of representatives from the city of Indianapolis, Indiana University, the , and the Midtown Economic Development Industrial Corporation (MEDIC) united to revitalize what had become known as the Midtown area via the demolition of the 18 Lockefield Gardens buildings that had closed. Indiana and Purdue universities’ expansion efforts for its nearby campus led to further depopulation of the Midtown neighborhood.

Seven of the remaining Lockefield Gardens buildings were maintained and restored and were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. Also placed on the register were the Walker Building (1980) and the 500 block of Indiana Avenue (1987). Efforts by the city to utilize the razed Lockefield land for urban renewal efforts also resulted in the construction of new apartments and Central Canal renovation in the 1990s.

The neighborhood now known as also experienced depopulation in the mid-1900s. First established in the 1890s, the neighborhood, like others in the vicinity, had been African American and had included small cottages. With the encroachment of IUPUI, the neighborhood declined. By the 1980s, many homes stood empty or were demolished. However, in 1992, the neighborhood was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and it became an Indianapolis in 1998. Ransom Place experienced new growth and revitalization. The remaining homes have been restored, and new ones have replaced vacant lots.

By 2021, any residential character remaining for Midtown was north of Indiana Avenue, primarily in the area behind Crispus Attucks High School—the location of the Flanner House Homes. In addition to Ransom Place, the historic district also has survived. South of Indiana Avenue, the expansion of the IUPUI campus, featuring structures like the Herron School of Art and Design, the IU Natatorium, the University Library, and numerous parking lots and garages, replaced what had been part of the historic African American neighborhood.

Shaped by mid-20th-century blight remediation and slum clearance, the demographic character of Midtown has changed since 1970. Once a predominantly Black area, the growing presence of IUPUI and the preservation and redevelopment of Lockefield Gardens and Ransom Place has resulted in a steep decline of African American residents and an increase in white, college-educated, young adults.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.