The Meridian-Kessler neighborhood derives its name from its western and northern boundaries—Kessler Boulevard and Meridian Street, respectively. The former Monon Railroad corridor forms the eastern boundary, and 38th Street bounds the neighborhood to the south.

The neighborhood’s history stretches back nearly 200 years to 1822, when it was first surveyed. Throughout the 19th century, the area now comprising the Meridian-Kessler neighborhood was distinctly rural, with half its land cleared for crops, pasture, or small apple orchards by 1880. During this era, the population hovered at under 2,500 residents.

Two homes remain from Meridian-Kessler’s pioneer era—the Hardin House at 4644 North Central Avenue, which was built around 1832, and the Oliver Johnson House at 4456 North Park Avenue, which was built around 1862. It is estimated that 27 homes constructed prior to 1900 still exist in the neighborhood.

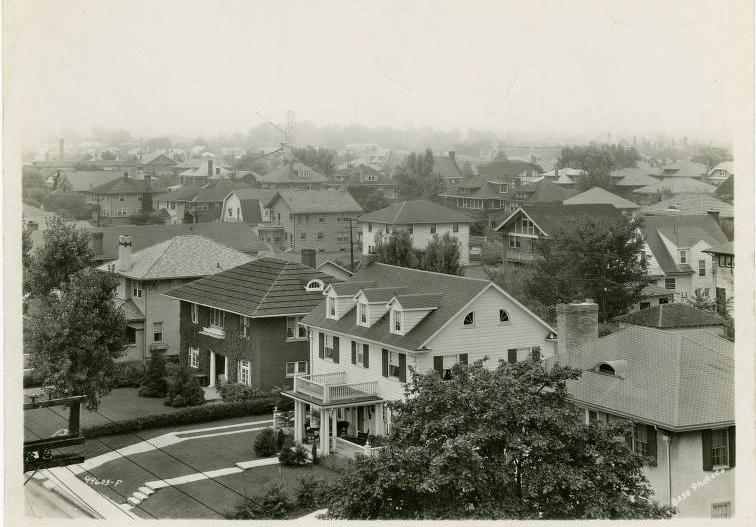

At the turn of the 20th century, the suburb of expanded south toward Indianapolis, and the residential growth of Indianapolis stretched further north, leading to the rapid development of the Meridian-Kessler area. The Broad Ripple line cut through the area and interurban trains weighing 40 tons and measuring 55 feet in length began rumbling down College Avenue connecting suburban residents to the city center. During these years, the streetscape of Meridian-Kessler began to take shape.

Meridian-Kessler has been a highly desirable residential neighborhood since this time. Prominent Indianapolis residents who have made the area their home include architect , U.S. Senator , architect , entrepreneur E. Howard Cadle, actress , newspaper artist and humorist , pharmaceutical industrialist , and author .

With the exception of the comprehensively designed and platted area of , the design and arrangement of lots in Meridian-Kessler was the result of private landowners subdividing parcels and determining street alignment and lot size on a piecemeal basis. Early land speculation resulted in an irregular grid, in which some streets such as Delaware and New Jersey are terminated randomly. By the 1920s, the area was subdivided, although not completely built.

Meridian-Kessler saw its most rapid years of development during the 1920s and 1930s. As a result, the neighborhood boasts examples of nearly every major style of early 20th -century architecture, ranging from the classic American four square, which predominates south of 44th Street, to bungalows east of College Avenue and large period revivals west of College Avenue. Throughout the neighborhood, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, and Classical Revival homes are intermingled, reflecting the choices of individual homeowners, builders, and architects nearly a century ago. The northside neighborhood became known for its leafy boulevards, well-preserved historic homes, and unique commercial nodes. But Meridian-Kessler’s distinct architecture tells only part of the neighborhood’s story.

The modern history of Meridian-Kessler is best told through the association that gave the neighborhood its name when, in 1965, the Meridian-Kessler Neighborhood Association (MKNA) was formed. MKNA sought to play an important role in achieving racial harmony by providing stable integration of an area that had once been almost entirely segregated. “We’re for integration…. and there are no exceptions,” said the Association’s 1968 President Mark Gross. MKNA’s initial philosophy reflected the attitudes and practices of the state’s civil rights commission, which sought integration of existing neighborhoods and sought to avoid “resegregation” where areas with all-white residents became areas with all African American residents. MKNA’s early logo even featured an interracial handshake.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, MKNA’s attention turned to redevelopment with a continued eye toward homeowner stabilization. For the past 45 years, Meridian-Kessler has hosted its annual home tour, originally organized in 1973 to promote “continued property improvement and esprit de corps” among residents. The neighborhood association began offering residents housing counseling in 1974, and in 1983, MKNA partnered with the and Watson Road neighborhood associations to work toward revitalization efforts at the intersection of 38th Street and College Avenue.

In 1986, the MKNA established the Meridian-Kessler Development Corporation with initial grant money from the to pursue neighborhood revitalization. The Corporation focused on the redevelopment of the intersection of 42nd Street and College Avenue and worked to secure the construction of an quadrant headquarters, the expansion of the Branch, and construction of a fire station. In addition, Meridian Street between 40th Street and Kessler Boulevard, which bisects the Meridian-Kessler and neighborhoods, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.

In the early 1990s, the Development Corporation purchased and rehabilitated homes in the southeast quadrant of the neighborhood with the goal of selling homes to low and middle-income residents and with a specific goal of avoiding gentrification. Neighborhood activism continued in the 1990s when the neighborhood became the first in Indiana to have curbside pickup of recyclable goods after the MKNA organized a program for the entire neighborhood.

By 2006, the neighborhood boasted more than 250 homes designated by the National Register of Historic Places as culturally or historically significant. The MKNA represents the largest neighborhood community in Indianapolis and aims to enhance livability, promote growth and capital investment, and preserve the neighborhood’s historic qualities.

Is this your community?

Do you have photos or stories?

Contribute to this page by emailing us your suggestions.