Indianapolis has been home to numerous libraries and archives since its founding in 1820.

The idea of public libraries was not new in the 1820s when Indianapolis was founded. Community libraries supported by a combination of tax dollars and private subscriptions had become common in New England at the end of the 18th century and served as an inspiration for the provision in the 1816 Indiana Constitution allowing for county libraries financed by the sale of town lots. The first efforts to establish libraries in Indianapolis were made shortly after the founding of the city, although it was not until after the Civil War that libraries began to flourish.

In spite of the provision for public funding, the first attempts to make books available to the public were private subscription libraries, beginning with the Indianapolis Library in 1828. This library, like the other subscription libraries, lasted only a few years before waning interest and lack of funds forced it to close.

Two more successful efforts to start libraries used public funds. Indianapolis attorney Henry P. Coburn started the Marion County Library in 1841, using a small amount of money that had been set aside from the sale of town lots as provided for in the 1816 Constitution. The money was not as much as it might have been, since the state legislature had diverted the Marion County monies to other purposes, but it was enough to purchase books and begin operations.

After some initial interest, use of the library declined because it charged a subscription fee and was open only for a few hours on Saturdays. In 1868, the library reported fewer than 100 subscribers. While it continued to function into the 1910s, usage remained low.

In the early 1850s, the state legislature approved funding for a system of township libraries as part of a new system of township schools. Through this program, supported by Indiana educational reformers Caleb Mills and Robert Dale Owen, the state government purchased and distributed collections of about 500 books for each township. The collections were used heavily in Indianapolis, as well as throughout the rest of the state, but as there was neither continued funding nor a local institution to maintain the program, the township libraries eventually closed.

The city’s principal library before the Civil War was the . The library was created to support the work of the legislature and state government officials, but it also played an important role in the intellectual life of the town. Its collections of historical, geographical, and literary works were widely read—novelist remembered reading James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving in the State Library’s reading room, while used its collections heavily when he was editor of the . Despite its importance to the young city, the State Library was inadequate to serve as a city library. Its books did not circulate to the general public, and despite Wallace’s experience, it contained very few popular works.

The absence of an adequate library was remarked upon by several writers. Libraries were seen as an essential continuation of the public school system, for without a library, adults were limited in how they could improve their reading and broaden their understanding of the world. Moreover, a strong public library was a mark of a city’s cultural interests and hence a sign that the city had arrived. During the pre-Civil War period though, the city had neither the size nor the prosperity to support a successful library.

Following the Civil War renewed interest in establishing a public library resulted in the creation of the Indianapolis Public Library in 1873 as part of school reform legislation prepared by Indianapolis School Superintendent . The legislation allowed the state’s largest cities to use property taxes in support of a public library placed under the control of the school board.

Public funding made the library a significant cultural force in the community from its beginning. At the time the library opened, it had the city’s largest collection at more than 12,000 books, a professionally trained librarian from the East—, and was open from 9 A.M. to 9 P.M. every day, including Sunday. People in Indianapolis were clearly ready for a library. They borrowed more than 100,000 books in 1874, the library’s first year of operation, and more than 300,000 10 years later, making it one of the most heavily used libraries in the country. Moreover, the library played an active cultural role in the city, as numerous literary societies formed around the institution, including the still-active .

Although under the jurisdiction of the Board of School Commissioners, the Public Library did not offer any special programs for children until the early 1880s when it printed its first juvenile books catalog and set up reference libraries in many of the schools. Under the administration of Eliza Browning (1892-1917), the children’s programs began to play an increasingly significant role. A separate children’s book section was established in the late 1890s, and shortly thereafter the library began holding after-school story hours. By 1917, the library circulated as many children’s books as adult books.

Browning also inaugurated the extension of library services into the city’s neighborhoods. The first four branch libraries opened in 1896, and by the end of her administration, there were 12 branches, including five funded by gifts from Andrew Carnegie. The branches were important in providing reading material to the city, accounting for more than 60 percent of the library’s circulation by 1920. The library saw the branches as neighborhood educational and social centers as much as book distribution points.

This educational role was especially important in immigrant neighborhoods, where the libraries ran language and culture classes and provided reading materials in people’s native languages. The branch library, one of the city’s busiest in the 1920s, provided books and newspapers in 14 languages, and the librarian made house visits throughout the neighborhood to encourage immigrants to come to the library.

Although the Indianapolis Public Library was the dominant library in the city by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were numerous other libraries. The two largest of these, the State Library and the Supreme Court Library, were run by the state government. Their primary users were state officials, court officials, and local lawyers. The state government also supported small libraries at a number of public institutions, including the Women’s Prison, the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane, and the .

By the turn of the century, there were also small but growing libraries at the increasing number of colleges and private professional schools. These had only small collections, though, ranging from a few hundred volumes at the to about 15,000 at in 1910. Because of their own limited book collections, these institutions expected their students to make use of the much more extensive collections of the Public Library.

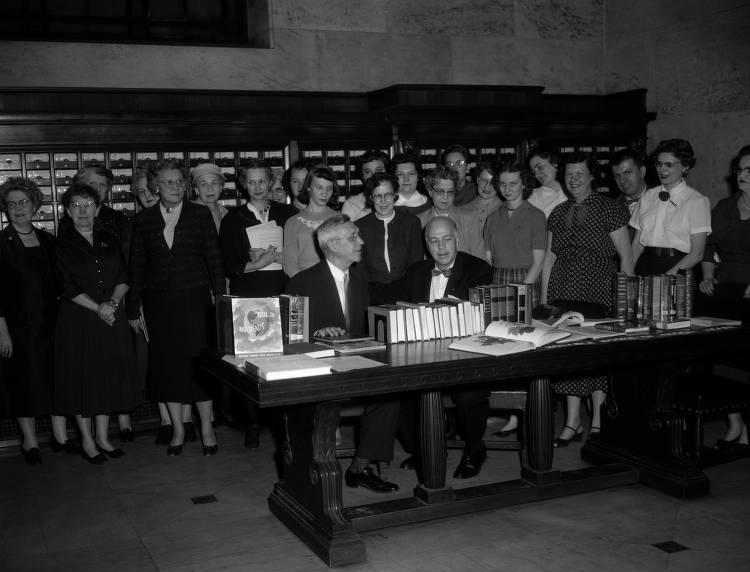

The growth of the libraries in the city was slowed by the Great Depression and World War II, but the demand for books continued to be high. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Indianapolis Public Library consistently ranked among the top five city libraries nationally both in the number of borrowers and the number of books circulated per capita.

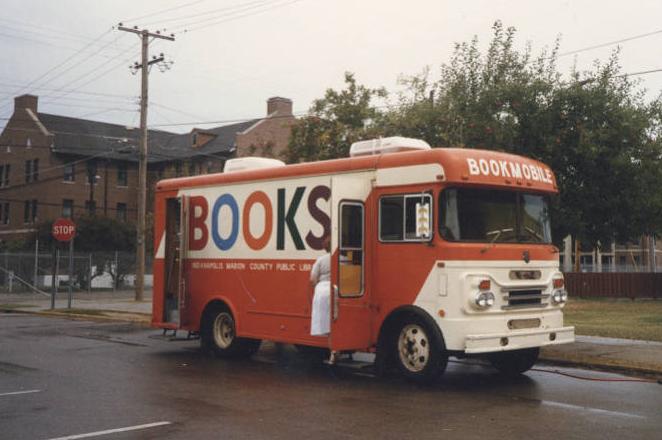

Since the mid-1950s, libraries in Indianapolis have experienced remarkable growth and change. The Public Library expanded in the mid-1960s by extending its services into the rapidly growing Marion County suburbs. As a result of the creation of a new , the institution added seven branches in the county between 1967 and 1971 and saw its budget for book buying more than double. In the process of expanding to the suburbs, the library separated from the Indianapolis Public Schools. The library had operated a School Services Division since 1917 to coordinate the provision of books for the city’s schools, but the division closed in 1968. By 2020, the public library system had 24 individual branches serving the community, including one located within the Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

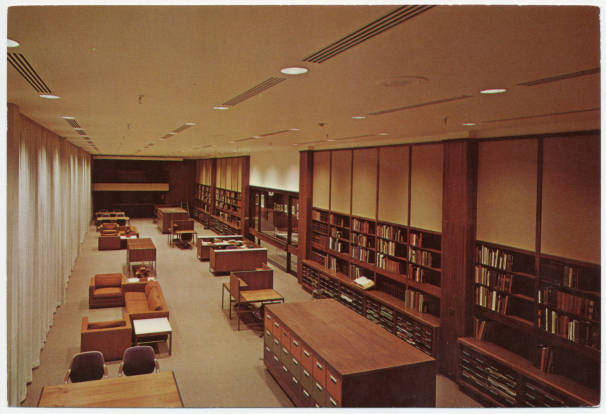

The academic libraries in the city have also grown dramatically since the 1950s. In part, this is the result of the growth of the schools themselves, particularly the Indiana University and Purdue University schools. More important was the changing nature of academic work, requiring faculty and students to have greater access to recent research, particularly in the scientific, technical, and professional fields. To house these growing collections, substantial new library buildings have been constructed on nearly every campus in the city since the early 1960s.

The increasing public need for specialized information resources has led the libraries in the city to devote increasing attention to sharing resources. In 1974, a group of 44 libraries in Indianapolis and the surrounding counties formed the (CIALSA) to improve services by sharing collections, expertise, and continuing education for staff. By the early 1990s, there were 150 participating academic, public, school, and business libraries, providing more than 1,000 books per month to patrons of the other member libraries.

The coming of automation in the 1970s led to substantial changes in the services libraries offer and in the way the libraries operate, making them increasingly connected to national and international information resources. By the late 1970s, most of the city’s major libraries were connected to OCLC (Online Computer Library Center), a national database of cataloging records that allowed them both to increase their cataloging efficiency and to have access to information about library holdings throughout the country.

In 1983, the Public Library was the first in the city to replace its card catalog with an online catalog. The State Library and the Indiana University libraries followed a few years later. By the early 1990s, the trend of library automation was to make information about library resources and ultimately the resources themselves, available to the public without going to the library. This trend continued into the 2000s, allowing the library to connect with patrons through online services such as providing access to online research materials, virtual programming, and the ability to send materials directly to personal e-readers and computers.

Despite library growth in the digital sphere, the brick-and-mortar library space continued to be a necessary part of the Indianapolis community. Beginning in the 1990s through the 2000s, the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library system completed multiple building updates as well as new building construction. As part of this, the Central Library branch completed a major renovation in 2007 which replaced the 1970s stacks and annex with steel and glass tower surrounding the historic portion of the building.

The history of archives and historical collections in Indianapolis is primarily the story of two institutions, the Indiana State Library and the private . As with libraries, several efforts were made before the Civil War to establish a collection of printed and manuscript materials on the history of the city and state, principally through the Indiana Historical Society. Lack of consistent funding and interest doomed these efforts, and most of the materials collected by the society before the Civil War were lost by the 1870s.

The State Library began to collect state historical records only in the late 1890s, coinciding with both the removal of the library from the direct control of the legislature and the growing national movement to preserve state historical records. By the time the State Library formally established its Division of Archives and History in 1906, it had already become the principal repository in the state for historical manuscripts and printed materials on Indiana history.

In the 1920s, the Indiana Historical Society reentered the field of historical collections as the result of a bequest of money and a historical library from newspaper publisher . The Historical Society’s search for a location for its new library coincided with the State Library’s campaign for a separate library building for its collections.

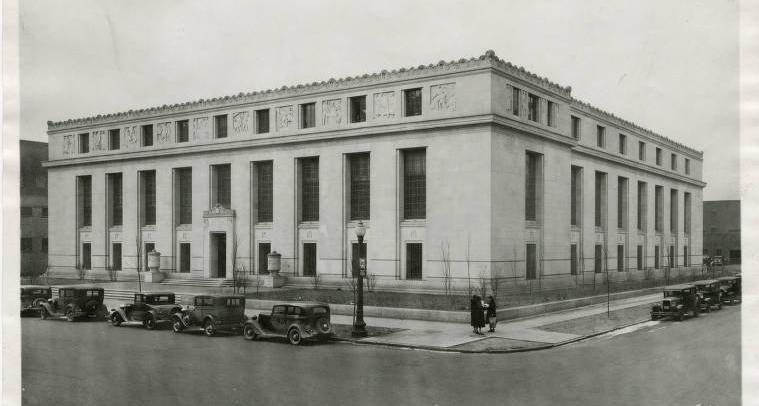

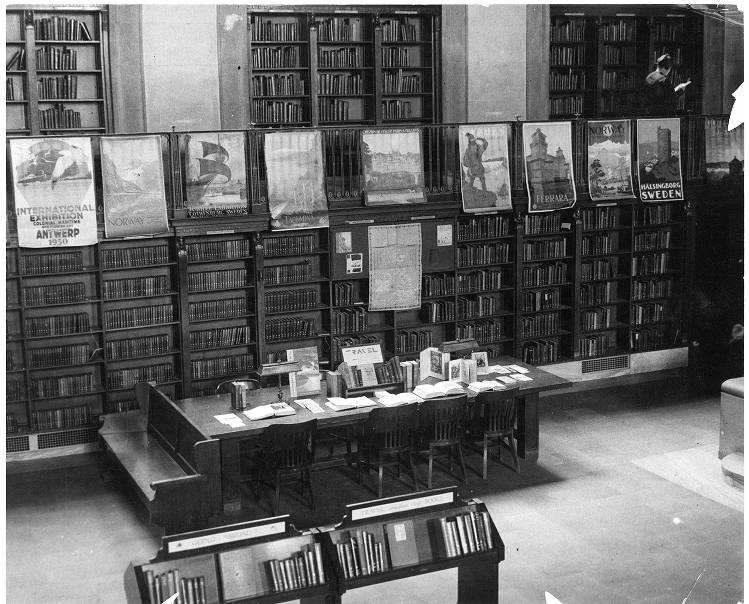

When the new opened in 1934, it included an area for the Historical Society’s library. Although efforts were made before 1934 to unite the two libraries administratively, they remained separate. The opening of the new State Library building was also the occasion for splitting the Division of Archives and History into three new divisions: the , which was responsible for the records of state and local government; the Indiana Division, which was responsible for printed materials and manuscripts on state history; and the Genealogy Division.

Over the following 30 years, the collections of both institutions grew slowly, as inadequate funding made it impossible for either of them to mount aggressive collecting programs. In the mid-1960s, the State Library was able to hire a field agent and began actively collecting the papers of modern Indiana politicians and contemporary organizations.

Since the late 1970s, the State Library has played a smaller role in preserving archival records on state history. In 1979, the Archives Division was separated from the State Library and merged into the new Indiana Commission on Public Records, and the gradual reduction of funding for the library during the 1980s caused the Indiana Division to curtail most of its active collecting of archival materials. During these same years, however, the Indiana Historical Society significantly expanded its collecting of 20th -century historical records following bequest to the organization that allowed for the substantial expansion of the society’s staff and programs.

In the 1990s, the Indiana State Library and the Indiana Historical Society parted ways. The Indiana Historical Society moved into a new building across the street in 1999. This new building included the William H. Smith Memorial Library as well as appropriate archival storage and conservation areas. With the historical society gone, the state library made the decision in 2001 to temporarily move the state archives to a separate location until a new building could be secured. This allowed space for much-needed renovations to the aging Indiana State Library building, which had already seen a basement flooding that caused severe damage to the archives materials prior to relocation.

In 2018, the Indiana Historical Bureau, which was also located at the library, merged with the Indiana State Library and continued to provide programs, publications, historical markers, and digital initiatives.

Two other important Indianapolis institutions maintain libraries and archives. The Indianapolis Museum of Art at includes the Stout Reference Library, which is a non-circulating collection available to Newfields staff, docents, students, collectors, and community members. The collection provides research materials on the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s collection and on the visual arts in general. The Stout Reference Library also houses a separate Horticultural Society Library that includes general reference books, magazines, and works on landscaping, specific plant families, and horticulture. The Library and Information Center contains resources pertaining to Indiana architecture and landmarks, historic preservation, restoration, and period decoration.

By the early 2000s, three new libraries/archives were established in Indianapolis. The first conceived in 1993 by Michael Bohr, populated at first by his own collection. The library was created with the intent to collect materials representing the history of gay life in Indianapolis. By March 1995, the library officially became a reality with sponsorship by the now-defunct Diversity, Inc. Indy Pride became the benefactor of the organization in 2008.

Another new organization, the was founded in 2007 by Michael Feinstein. The foundation was formed to collect and preserve the musical legacy of America as well as educate through exhibits and programs. It currently is associated with the in Carmel.

In 2009, the life and work of Kurt Vonnegut was highlighted with the founding of the . This library was created to house collections of materials related to Vonnegut and to educate through exhibits, workshops, and events.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.