Landscape architect and urban planner (1862-1923) of St. Louis, Missouri, created the first comprehensive plan for parks and boulevards in Indianapolis in 1909 and assisted in its implementation. It provided a sound framework for the expansion of the city well into the 20th century and remains a vital part of the city’s infrastructure.

Although Kessler should be given credit for the design and success of the plan, the park movement in Indianapolis predates his plan by several decades. In 1894, the Commercial Club (forerunner of the ) hired landscape architect Joseph Earnshaw of Cincinnati, Ohio, to prepare a park plan for the city. Earnshaw recommended that a new boulevard, lined with parks, parallel and from Washington Street to the current site of the . His plan was rejected as too extravagant, but the Park Board in 1895 endorsed a similar plan initiated by the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot (Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., John Charles Olmsted, and Charles Eliot) from Brookline, Massachusetts. A new state law in that year enabled cities of 100,000 or more to create park agencies.

The Park Board and the Olmsted plan came under attack almost immediately. The issue of cost was the subject of much debate, and residents of the east and south sides argued that while the entire city would be assessed for the improvements, the plan would benefit only the north side. Then, in 1897, the state enabling law was declared unconstitutional.

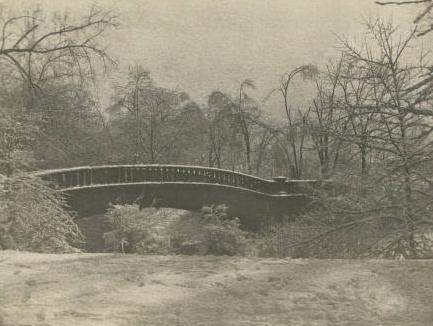

Passage of a new state law in 1899 did not resolve the local controversy, and the progress of the parks and boulevard system was sporadic until 1907. The most important events were the acquisition of Riverside Park (not recommended in the plan) and the replacement of several old iron with stone-clad arched spans. J. Clyde Power, the city engineer, designed these handsome bridges which cross White River and Fall Creek. Several still stand. In 1912, Kessler would design a similar bridge to carry Capitol Avenue across Fall Creek.

By 1907, the city clearly needed a single guiding vision for its boulevard and park system. From 1908 until 1915 the Parks Department retained Kessler, a well-recognized planner, as a landscape architect. He was born in Frankenhausen, Germany, raised in Dallas, Texas, and formally trained at the Grand Ducal Gardens in Weimar and the University of Jena. He had designed park and boulevard plans for Kansas City, Missouri (1892), and Cincinnati (1907), as well as planning the Louisiana Purchase Exposition grounds in St. Louis (1904).

Kessler retained aspects of both the Earnshaw and Olmsted plans, including the concept of a linear park lined by boulevards along White River and Fall Creek. The Kessler plan, however, was far more comprehensive in scope than its predecessors. It linked all the public open spaces in the city with a system of broad parkways to follow the four major waterways in Marion County: White River, Fall Creek, Pleasant Run, and .

The plan took advantage of those features that the city offered: picturesque, meandering streams, broad vistas, and fine stands of timber. Kessler’s plan was also practical since it protected waterways from pollution and acted as a device. In addition, it tied existing thoroughfares, such as Meridian Street, Washington Boulevard, and 38th Street (Maple Road), to the boulevard system and called for their beautification. Kessler quelled the opposition shown to previous plans by dividing the city into separate taxing districts, a strategy also incorporated into a new state park law (1909).

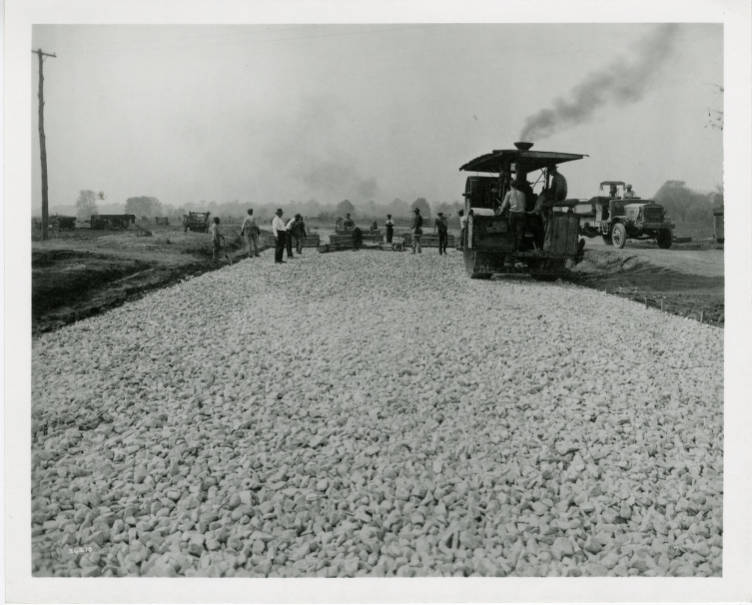

Over the next several years, Kessler’s firm produced designs for new and existing city parks, including (1914), (1915), and Riverside Park (1916). In October 1922, the Board of Park Commissioners once again hired Kessler to plan extensions to the boulevard system on the north side. He recommended that be connected to the northwest side of town by a leisurely route. Following parts of existing Cooper Road, 59th , and 56th streets, the thoroughfare was to include a 100-foot roadbed and bridle paths. Work had just begun on the boulevard when Kessler died in March 1923, in Indianapolis. The parkway, named Kessler Boulevard in his honor, was completed by 1929.

By placing parks and boulevards in strategic locations, Kessler’s plan fostered residential growth in sparsely populated areas and reinforced the tendency of citizens to regard the north and east sides of the city as desirable neighborhoods. Ideas first presented in the Kessler plan still influence planning in Indianapolis. It was Kessler who in 1909 recommended that a public court of government buildings and parkland extend west of the . This idea has been followed in spirit with the completion of the South building and planning for .

George Kessler’s most prominent legacy in Indianapolis remains visible in the ways his greenways have connected distant parts of the city through the transformative pedestrian and vehicular “green” transportation routes (see ). His greenway system continues to guide urban growth, preserve the environment, protect water from pollution, and provide flood control.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.