Census data from 1880 onward reveals the small number of Japanese in Indiana, without a true Japanese-American community either in the state or the capital on the eve of World War II. Those Japanese who came to America in the two decades before and after the turn-of-the 20th century were part of the second wave of immigration that included Southern and Eastern Europeans. Most of the Japanese immigrated to Hawaii or the states along the West Coast. Those in the Midwest were predominantly found in the Old Northwest states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. However, with the largest population of white, native-born citizens in the United States Indiana never became home to many Japanese.

Indiana maintained an anti-immigrant stance that was out of step with the rest of the Midwest. In 1905 and 1906, the and the investigated several “representative” Japanese-Americans who had settled in the city. The papers questioned why they came here and whether they intended to remain as permanent residents. While the press was not entirely negative, it questioned whether the Japanese were here simply to learn American industrial methods for the purpose of transporting these new technologies back to Japan.

In 1907, the restricted immigration with the Indianapolis Commercial Club supporting that position. The 1910 U.S. Census counted only 14 individuals of Japanese descent living in Marion County.

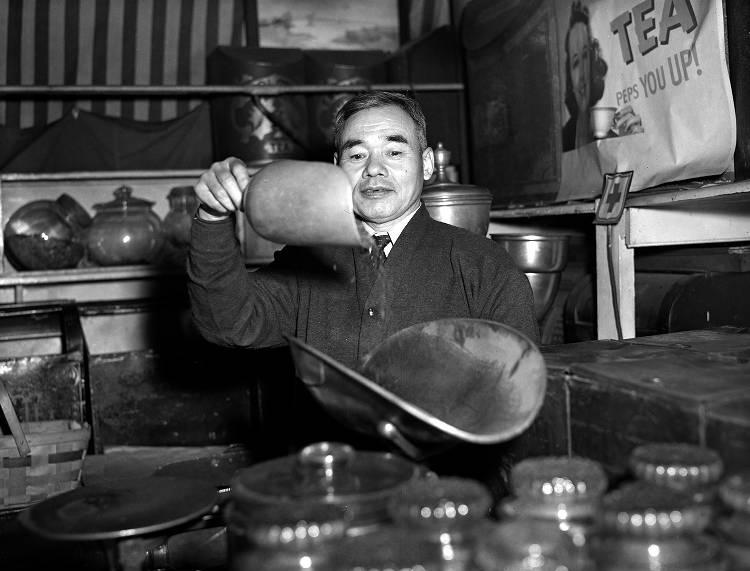

With the advent of restrictive immigration laws beginning in the 1920s, the Indianapolis-based was one of several national groups that lobbied successfully to bar Japanese Americans (including those born in the United States) from rights of citizenship. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 appeared to vindicate the Legion’s stance. In the days following the bombing of Pearl Harbor the was hard-pressed to find two Japanese in Indianapolis to interview about the attack. The paper finally interviewed Professor Toyoto W. Nakami at Butler University and Harry Sasaki a coffee and tea vendor at City Market.

During World War II, not all Hoosiers supported anti-Asian sentiments. In 1943, the published an article that discussed the availability of Japanese from relocation camps who could be recruited to fill a number of jobs, if the community was willing to accept them. The following year the commended a Legion post in New York for admitting several Japanese American soldiers (calling them “patriots”) who had been rejected by a post in Oregon.

Still, the International Teamsters headquartered in Indianapolis opposed Japanese resettlement. The Marion County Building Trades Council protested the War Relocation Association (WRA) relocation effort in the first place, though the CIO supported it. The WRA asked Indianapolis government officials, business leaders, and the American Legion about Indianapolis residents’ sentiments toward the Japanese before bringing them to Indiana. The United States Missionary Society countered opposition to resettlement by stating that the Japanese worked in the service and agriculture industries, sectors where white Indianapolis residents were amenable to see Japanese employed, which calmed some fears.

African Americans were leery of resettlement, fearing job loss and housing insecurity. Though some white Indianapolis residents accepted the arrival of the Japanese to the city, the African American Church Federation of Indianapolis opposed the relocation of Japanese, maintaining that Indianapolis was not ready for the influx of immigrants.

Religious denominations engaged in international missionary work took a transnational view of the world, which helped to bring Japanese and Japanese Americans to Indianapolis. Protestants belonging to the Church, whose international headquarters was in Indianapolis, took the lead in relocation efforts. Leaders of the Disciples of Christ worked to move Japanese and Japanese Americans from internment camps to towns and cities across the nation.

The number resettled in Indiana was low but still represented a 10-fold increase in the Japanese population by the end of World War II. The WRA organized a field office at the Circle Tower in downtown Indianapolis to help the Disciples of Christ Church place the Japanese in towns where residents were willing to accept the evacuees.

The United States Missionary Society also retained its headquarters in Indianapolis. This group worked with other church groups during the relocation of the roughly 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans from internment camps to other states. The Society helped with job placement. Catholic and Jewish groups collaborated with the Protestants in this effort.

By 1943, there were 254 Japanese in Indiana with 202 Nisei (Japanese Americans born in the U.S. to parents who were born in Japan). Another 250 Japanese who fought for the United States were captured at Pearl Harbor and brought to , where they performed menial tasks. Some were permitted to fight in the 100th Indiana Regiment in the European theater of World War II.

The Disciples of Christ continued to work toward relocating those Japanese detained in camps to Indianapolis. By the end of 1944, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. War Department worked to spread the information that the detainees were not the people responsible for the Pearl Harbor attack. Civic leaders such as , Rowland Allen of the department store, Mrs. H. Baumgartel of the , and Howard Nyhart of the played key roles in the acclimation of Japanese into Indianapolis society. convinced the Indianapolis African American community to accept the Nisei, if not the detainees.

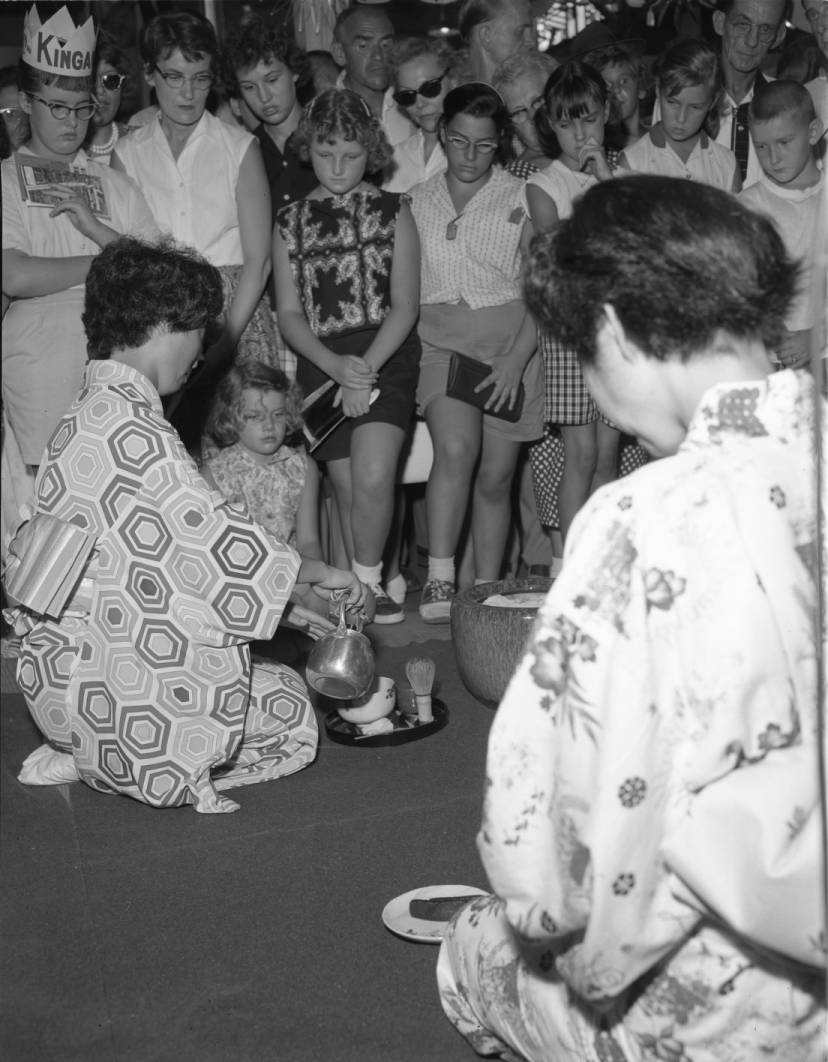

To assuage apprehensions that Indianapolis residents and Japanese immigrants held about each other, Indianapolis photographer Charles E. Mace initiated an internal advertising campaign that depicted both Indianapolis and Japanese in the best light. He published photographs of Japanese immigrants working on farms in Plainfield, Indiana, waitresses working in Indianapolis restaurants, and churchgoers attending service among white Indianapolis residents. These images portrayed an Americanized Japanese population, not the traditional Japanese immigrant detainees dispersed from detention camps to Indianapolis.

Mace’s Japanese Americans represented the Christian, non-agricultural Nisei. They were middle-class English-speaking citizens who grew up attending American schools and living in American neighborhoods. Many were college students who attended universities like Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. Most of the World War II-era Nisei were in their 20s and 30s.

The number of Japanese who remained in Indianapolis, and Indiana, dwindled after the war, especially after the WRA left their Indianapolis office in February 1946. Part of the reason stemmed from strict preselection procedures implemented for Japanese immigrants who wanted to live in Indianapolis. Applications were scrutinized with permanent residency granted only to people deemed to be superior. The WRA took personal responsibility in the relocation effort, but with their absence negative sentiments resurfaced. After the WRA office closed, many Japanese returned to the Western states from where they came.

By 1950, 46 Japanese residents lived in Marion County, 37 in Indianapolis. Over the next decades, the city’s Japanese population (Japan-born and American-born of foreign parents) increased from 263 in 1960 to 753 (824 in Marion County) in 1990.

Japanese making their home in Indianapolis organized a Hoosier chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League in 1976 and the Japan-America Society of Indiana in 1988. The Minyo Dancers have worked to combat racial discrimination and to provide programs of intercultural awareness. Groups like the Japan-America Society have continued their work into the 21st century. Indianapolis is also a chapter of the SGI USA Indiana, which is part of the Soka Gakkai International movement, a form of Japanese Nichiren Buddhism.

In 2020, Japanese comprise less than 1 percent of Indianapolis’ population, with a somewhat larger percentage living in the surrounding counties.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.