Photo info ...

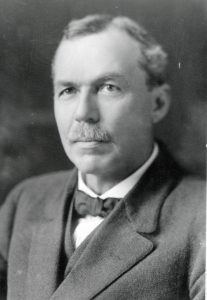

(Apr. 12, 1855-June 6, 1924). Born in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, Dunn came with his parents to Indianapolis in 1861 and attended the city’s public schools. A precocious student, he graduated from Earlham College (B.S. 1874) at age 19 and from the University of Michigan (LL.B. 1876) at 21. After practicing law in Indianapolis for a few years, he was sent by his father (along with two brothers) to Colorado in 1879 to look after investments in silver mines. He stayed for five years, prospecting for silver, researching Indian history, and working as a reporter for newspapers in the Denver and Leadville areas. Dunn returned to Indianapolis in 1884, where he made his permanent home.

Dunn first achieved public notice in 1886 with the publication of . The first scholarly treatment of the subject, based extensively on government documents, Dunn’s book was quickly recognized as a minor classic and is still respected by students of frontier history. It was reprinted in 2002 by Stackpole Books as the first of its Frontier Classics Series.

The reputation of prompted Houghton Mifflin to invite Dunn to write the Indiana volume for the series. His (1888; rev. ed., 1905), analyzing the history of the slavery issue in Indiana territorial politics, was well received. Meanwhile, Dunn had joined with Indianapolis historians and Daniel Wait Howe to improve the dilapidated and to revive the comatose (IHS), organized in 1830. Dunn became recording secretary of IHS in 1886, leading to its revival and expansion. Elected state librarian by the state legislature for two terms, 1889-1890 and 1891-1892, Dunn was able to improve the library’s condition notably. He also served on the Public Library Commission from its inception in 1899 until 1919 (president, 1899-1914).

Dunn, a Democrat (see ), supported himself principally by his work as a journalist, writing political editorials for Indianapolis newspapers. His leadership of progressive reforms such as the Australian ballot (1889), the city charter (see ), and the tax reform of 1891 had a significant impact on the city’s politics. He also ran for Congress, unsuccessfully, in 1902, and he served two terms as (1904-1906, 1914—1916).

Dunn produced a large number of historical works. He wrote five monographs for IHS and edited the first seven volumes of its . He wrote for scholarly journals of history and political science and for biographical publications. His crowning achievement was (1910), in two volumes (volume II is biographical). The first volume is among the finest of local histories, demonstrating an intimate knowledge of the city, a critical view of its development, and a lively appreciation for the personalities and events he describes. (1919), in five volumes (three are biographical), also reflects Dunn’s command of the sources and his evenhanded approach. Both works remain indispensable sources for Indiana history.

Dunn made contributions to Native American ethnology after 1905 when he began the regular study of the Miami language with the aging Miami Indians Gabriel Godfroy of Peru and Kilsokwa, a granddaughter of Little Turtle, a chief of the Miami who gained notoriety during the period that U.S. Congress launched a campaign against Native Americans who raided early white settlers in the Northwest Territory. Supported in his studies by the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology (1908-1909, 1911-1913), Dunn created a dictionary that has helped to preserve the Miami language, though it died as a spoken language.

After a two-month trip to Haiti, prospecting for manganese in the winter of 1921-1922, Dunn joined the campaign staff of Samuel Ralston, who was elected to the Senate in 1922 and served as Ralston’s chief aide in Washington until Dunn’s death in 1924.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.