The earliest organized effort to preserve local history appears to have been the founding of the (IHS) on December 11, 1830. Prominent state figures including John Hay Farnham (principal founder) and , as well as Indianapolis residents , , , , , and , were among the society’s first leaders.

A rather inactive organization during its formative years, the IHS collected historical records, developed a library collection, and sponsored publications on local history. John B. Dillon, the Virginia-born editor of the (1834-1842) and author of the first history of Indiana (1843), served as state librarian (1845-1851), thereby developing the principal repository of the state’s historical materials in Indianapolis.

In an 1853 program for the historical society new state librarian delivered what may have been the first lecture on Indianapolis’ early history. The IHS subsequently published the lecture in 1897. Reflecting the growing historical awareness of the period (as well as a desire to preserve their place in the annals of local history), several of Indianapolis’ founding families formed the Marion County Old Settlers Association, which met for the first time on June 6, 1854, at the home of .

Established “to perpetuate the names of the first settlers of Marion County, to embody the history of the early times, and transmit the same to future times,” the group, which elected Calvin Fletcher president, claimed 55 members who had settled in Indianapolis between 1820 and 1825. By 1856, when James Blake hosted the annual meeting, nearly 600 people attended. In 1857 the association met at the where several hundred attendees heard memorial addresses, viewed exhibits of artifacts and daguerreotypes of the early settlers, and ate dinner.

As local attention turned to the Civil War, the regular commemoration of the pioneer years faded until being resurrected by the during the state’s centennial (1916). Two key events at midcentury proved to be significant for local history in the capital city. In 1857 Indianapolis-born lawyer wrote the first comprehensive history of the city, which he later expanded for . This document provided Indianapolis with a detailed timeline of its past.

The other significant event was the death in 1866 of Calvin Fletcher, who had kept a diary since his arrival in Indianapolis in 1821 and also had saved and bound a series of local newspapers. By bequeathing these items to the IHS Fletcher left a valuable historical record, one which provided a detailed view of daily life in early Indianapolis.

Although July 4th observances had been a continuous part of Indianapolis’ public celebrations since the 1820s, the nation’s centennial (1876) inspired local citizens to mark the occasion in a magnificent manner. Organizers mounted a large parade with marching bands and elaborate floats representing “The Discovery of America,” “The Landing of the Pilgrims,” and “Emancipation,” most of which were sponsored by local German organizations. Young women staged tableaux representing the 13 colonies and the Goddess of Liberty, while men from German and French fraternal societies portrayed George Washington and other Revolutionary War generals. The day concluded with commemorative speeches and balloon ascensions. The nation’s centennial coupled with the emergence of the historical profession renewed interest in the study of local history.

In 1884 , editor of the , published , a comprehensive political and biographical narrative. Two years later , , Daniel W. Howe, and others helped to reorganize the Indiana Historical Society. With a restricted membership, however, the focus of the IHS was elitist. It emphasized the state’s “great white men” and their families. More recently, IHS has worked to diversify its collections to document all segments of the population. In 1999, IHS moved into the Eugene and Marilyn Glick History Center, which gave the society the opportunity to mount public exhibitions and events inside its own facilities.

In 1910, Dunn’s monumental two-volume history, was published. has served as the definitive resource on early Indianapolis history ever since. During the following decade, Indianapolis participated in two major celebrations. Indiana observed its centennial in 1916 with statewide celebrations coordinated by the Indiana Historical Commission. There were scattered observances (pageants, historical markers, lectures, pioneer exhibits) throughout Marion County, including an elaborate pageant prepared by historian for the town of .

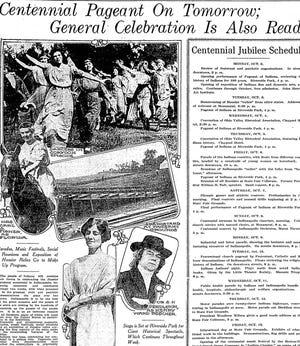

The principal state observance, however, was the Centennial Jubilee, held October 2-15, 1916, in Indianapolis. For two weeks sites around the city hosted expositions, parades, athletic contests, concerts, drama and dance programs, and commemorative addresses by politicians including President Woodrow Wilson and his immediate predecessor, William Howard Taft. The most ambitious commemorative program was the “Pageant of Indiana.” Written and directed by New York pageant expert William Chauncy Langdon and staged at Riverside Park, the pageant used 3,000 performers to trace Indiana’s history beginning with French explorer La Salle’s visit in 1679. As with all of the centennial celebrations this presentation emphasized progress from pioneer to industrial society and instilled a sense of confidence about the future. Kentland, Indiana, native and popular humorist, George Ade used the new media of film to create a silent movie for the centennial that followed the same narrative and portrayed as its narrator.

Four years later Indianapolis marked its own centennial with a week-long schedule of parades, pageants, music concerts, and special events. Resembling the elaborate festivities of the state centennial, Indianapolis’s program was highlighted by concerts at the State Fairgrounds, parades, fireworks, and a historical pageant. Designating and marking historic sites has been another method of remembering the past. In February 1917, the Indianapolis Park Board considered a proposal to mark the spot of cabin on , to which the responded, “Other cities take great pride in preserving places of historical importance. Why not Indianapolis?”

Since 1947, the Indiana Historical Bureau has designated historically significant locations with permanent cast aluminum markers with raised gold lettering and a blue enamel background. Marion County has more historical markers than any other in Indiana. There are many other efforts to document and mark sites of architectural, religious, and ethnic significance. The emergence of historic preservation and the creation of museums have also served to increase public awareness of and appreciation for the city’s history.

In 1934 , inspired by John D. Rockefeller’s restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, purchased the William Conner house in Hamilton County to preserve the site where state capital commissioners first met in 1820 and to recreate pioneer Indiana for the visiting public. opened to the public in 1964. Lilly also helped found (1960), which acquired the in 1962 and later opened it to interpret mid-to-late-19th -century decorative arts and life in Indianapolis. In 2011, Landmarks opened its headquarters at the former Central Avenue Methodist Church.

Similarly, the creation of historic house museums like the and the demonstrated a desire to document and preserve the history of Indianapolis’ important and influential citizens.

At the same time, ironically, urban renewal and redevelopment led to the demolition of many significant historic structures in the downtown and surrounding neighborhood areas, thereby severing the present’s tie with the past. During the 1960s and 1970s three key events—the demolition of downtown’s historic buildings, the city’s sesquicentennial in 1971, and the nation’s bicentennial in 1976—contributed to increased public interest in local history and resulted in the formation of several local historical societies.

The (1961) organized to preserve local history materials and to oppose the proposed demolition of the old county courthouse. The MCHS continued to work to save historically significant buildings and public sculpture through the early 1990s. As of 2020, the MCHS maintains a website that highlights aspects of Indianapolis history. For the city’s bicentennial, the website includes a city timeline and a blog that covers events that occurred during the city’s centennial in 1920. MCHS also provides occasional public programming.

The Irvington Historical Society (1964), which occupies the restored , started as an effort to preserve that neighborhood’s vibrant history. The Franklin Township Historical Society (1975) occupies the former Big Run Primitive Baptist Church (1871). The Beech Grove Historical Society (1978) began as a result of a local school project to prepare a history for ’s diamond jubilee. Decatur, Pike, and Wayne townships also maintain historical societies.

In 1967, the city established the (IHPC) to identify, preserve and protect historically significant structures and neighborhoods in Marion County. The IHPC helps with design and zoning and designates local , conservation districts, and individual historic properties. The Meridian Street Preservation Commission, established with the Meridian Street Preservation Act of 1971, operates separately from IHPC to protect the .

Indianapolis offers museums that reveal different aspects of Indianapolis history. The was incorporated in 1969 to preserve the Old Pathology Building at . Located in the oldest remaining firehouse building in the city, the Indianapolis Firefighter’s Museum opened in 1996.

Public commemorations and celebrations, like those surrounding Memorial Day and July 4th , once possessed a strong historical focus and invited people to consider their place in time. Even the city’s largest commemorative event—the dedication of the in May 1902— proved to be a joint memorial service-history lesson. Despite the presence of numerous historical organizations Indianapolis’s collective sense of its historical past has waned over the decades. Few public observances today, although patriotic in tone, actually evoke a sense of the historical past. This condition may reflect the dominance of a culture of entertainment and leisure and the absence of a public historical identity.

The city, however, hopes to revive interest in its history with its bicentennial celebration, which began in June 2020. The celebration extends to May 2021 because it is designed to commemorate founding events in both 1820 and 1821. The Bicentennial Commission has identified a number of official bicentennial projects, including the digital , the “Indiana Legends” Bicentennial Mural Series, and IHS’s Indianapolis Collecting Initiative.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.