(Feb. 29, 1824-June 2, 1906). Harrison Horton Dodd was an Indianapolis businessman and one of the leaders of secret organizations in Indiana that plotted violent uprisings against the authority of the United States government during the American (1861-1865).

Born in Brownville, Jefferson County, New York, Dodd was the son of a steamboat captain on Lake Ontario. The family relocated to Toledo, Ohio, in 1832. He attended Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, for two years (1843-1845), and in 1847 he married Ann Maria Bradford.

Dodd entered business in Toledo and served on the city’s Board of Public Works. In 1855 he ran for mayor on the American Party ticket (also known as the “Know-Nothing” party) and lost. The party espoused anti-German, anti-Irish, anti-Catholic nativist positions.

In 1856 he moved to Indianapolis. During that year his brother, John W. Dodd of Marion, Grant County, Indiana, won the office of auditor of state and served a four-year term (1857-1861) in the Statehouse as a member of the . Dodd served as his brother’s deputy. While in Indianapolis he established Dodd and Company, a job-printing and bookbinding firm located at 16 ½ East Washington Street. By 1864, at the height of Dodd’s political power and influence, the firm employed twenty workers.

From the start of the Civil War, despite holding no public, elective office, Dodd became influential in Democratic Party politics in Indianapolis and the state. He did so to oppose the war policies of the Republican administration of President Abraham Lincoln in putting down the Confederate rebellion.

By 1862 Dodd was speaking frequently all over Indiana to Democratic audiences urging opposition to the war. In his public speeches, he espoused state sovereignty views, asserting that the federal government had no authority over the states. States were sovereign and had the right to secede from the national union. No one owed loyalty to the federal government, he argued. Believing that abolitionists and anti-slavery Yankees had driven the southern states to rebel, he stated that the U.S. Constitution gave no authority to the federal government to coerce the seceded states back into the Union.

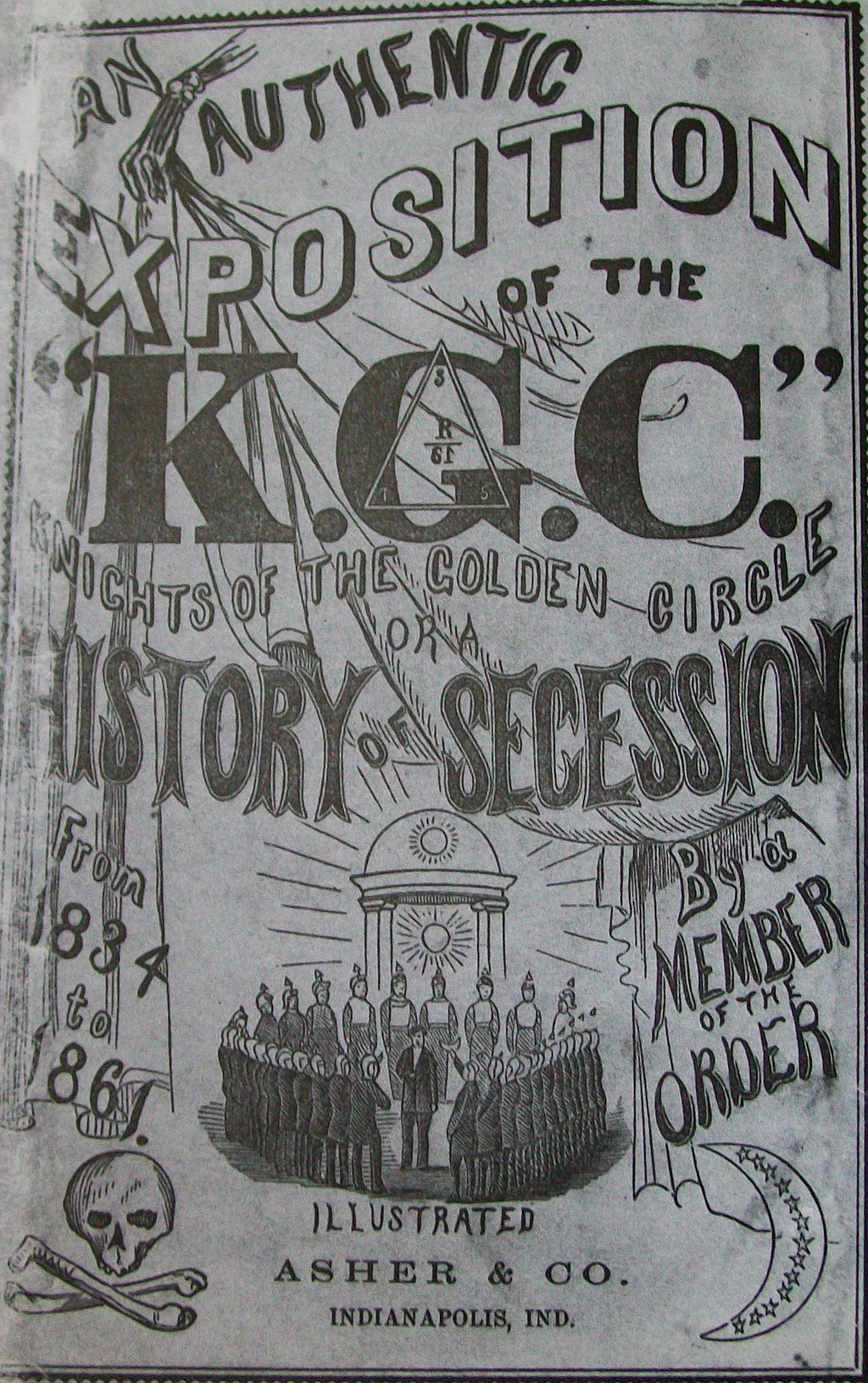

In public speeches, Dodd alluded cryptically to the existence of an organization called the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC), a secret oath-bound society formed in the 1850s originally to spread southern slavery into Central and South America. During the rebellion, its northern members supported the Confederate rebels. Members of the KGC and its successors held state sovereignty, pro-slavery views.

Although Dodd denied the existence or knowledge of the organization in his speeches, he secretly was active in organizing the KGC around the state. The group opposed laws and government measures to support the war effort. Members obstructed the draft enrollment and shielded draft dodgers and deserters from arrest.

Numerous violent incidents occurred in Indiana and other states in which armed and organized groups disrupted draft enrollments or rescued arrested deserters. Numerous enrollment officers were murdered or otherwise assaulted. U.S. Army commanders who investigated the KGC believed that the organization numbered in the tens of thousands in the state was tied closely to the Democratic Party and was behind much of the violence.

Dodd spoke at public rallies in which audience members carried firearms; sometimes he was escorted by armed bodyguards. Some of these rallies devolved into violence, as in March 1863 near Danville when an armed crowd attempted to pull down a U.S. flag, or at Gosport in May 1863 when a shooting occurred. In Rensselaer in September 1863, after giving a fiery speech denouncing the federal government, hundreds of armed men assembled quickly and demanded Dodd’s release when they believed he had been arrested.

In late 1863, the Knights of the Golden Circle reorganized and changed its name secretly to the Order of American Knights (OAK). Dodd became the organization’s state commander. One of his printing-office employees served as its secretary.

Dodd continued to travel the state organizing and rallying members. In addition, he traveled to other states and met secretly with other leaders of the organization. In a February 1864 meeting in New York City which Dodd attended, the OAK changed its name to the Sons of Liberty (SoL) and selected Clement L. Vallandigham of Ohio as its supreme commander. Dodd remained as grand commander for Indiana.

In 1864 Dodd communicated with leaders of the Sons of Liberty organization of other states in efforts to plot armed uprisings. These leaders acted in coordination with Confederate spies and agents. Dodd pushed for an Indiana uprising to occur in mid-August, during which armed men would assist the thousands of Confederate prisoners held in to break out. Men assembled in Indianapolis on the appointed day, but alarmed Democratic officeholders who were aware of the movement succeeded in halting the attempt.

Days later, Indiana governor obtained word from an informant that arms and ammunition were being shipped from New York to Dodd in Indianapolis. Troops found and seized boxes marked “Stationary” [sic] containing hundreds of revolvers and 135,000 rounds of ammunition in Dodd’s printing office. Morton notified military authorities in New York who intercepted an additional 2,000 revolvers destined for Dodd’s office. Several of Dodd’s workers were arrested. Also found in Dodd’s office were records of the SoL organization, including membership rosters and correspondence. Morton had many of these records published in the the state Republican Party organ. Dodd, himself, was absent from Indianapolis.

Dodd was in attendance at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a delegate; he also attended the simultaneous secret meeting of Sons of Liberty heads held during the convention. Local Sons of Liberty leaders had planned to stage an armed uprising in Chicago during the convention. Confederate troops were present to assist in the rising, but, to their disgust, the locals became unnerved by the (false) rumor that thousands of U.S. troops had arrived by train. They put off the rising.

In early September at the end of the Democratic convention, Dodd returned to Indianapolis and was promptly arrested by military commanders and held in prison. Military authorities, with the blessing of President Lincoln, prepared to put him on trial by military commission on charges of disloyalty and conspiracy.

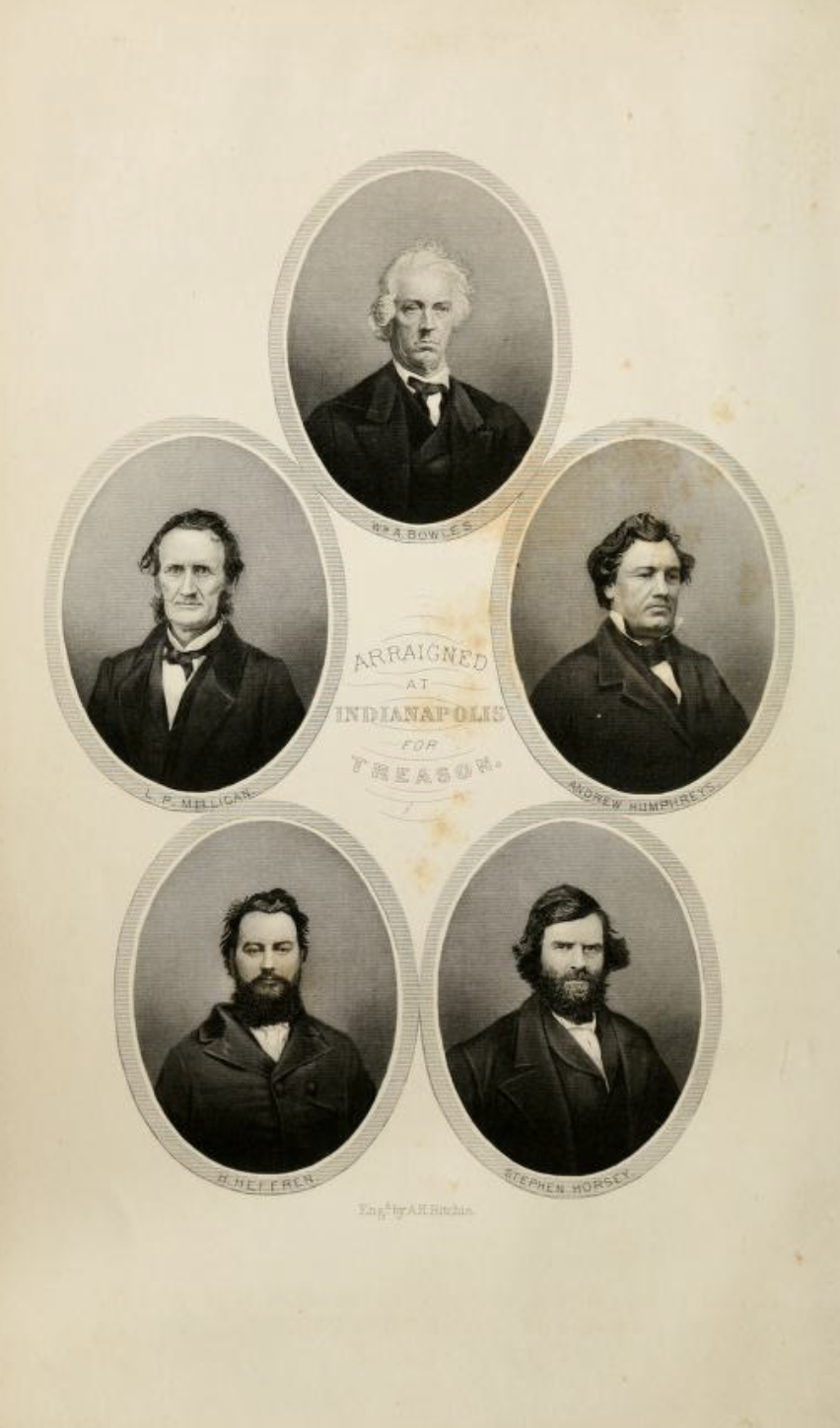

The Indianapolis treason trials, open to the public and reported in detail by newspapers, provided sensational details of conspiracy by Dodd and other prominent Democrats. Military commanders ordered the arrest of several fellow state Sons of Liberty leaders. However, Dodd, with assistance from outside persons, escaped through an upstairs window of his cell in the Post Office and Federal Courts building.

Embarrassed military officers made careful attempts to rearrest him but failed. He soon was spotted in Canada. As the responsible officer explained in a report, Dodd and his brother, John W. Dodd, had offered their word as gentlemen that he would not attempt to escape. Officers mistakenly had taken Dodd at his word. The military commission found him guilty and sentenced him to death in absentia.

Dodd lived in exile in Canada until after the release of fellow conspirators Lambdin P. Milligan and William A. Bowles pursuant to orders from the U.S. Supreme Court in April 1866. In its later ruling, Ex parte Milligan, the court decided that civilians cannot be tried by military tribunals where and when the civil courts are open.

Dodd returned briefly to Indiana but, though the U.S. attorney declined to indict him for his wartime conspiracy, found he was not welcome. He took up residence in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and worked as the agent of the American Express shipping company. In 1868 the company transferred him to Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, whose citizens ignored his misdeeds and where he became a community pillar. In 1874 he won election as mayor of the town.

Throughout his life, in Ohio, Indianapolis, and Wisconsin, Dodd was active in fraternal, secret organizations such as the International Order of Odd Fellows and the Order of Elks, groups that had wide membership among American men and played prominent roles in male culture. His membership in the nativist Know-Nothings in the 1850s and the KGC/OAK/SoL during the Civil War, secret political groups which sported the oaths and rituals and other trappings of more benign fraternal groups, fit the pattern of a lifetime.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.