Several interconnected cemeteries formed the original Greenlawn Cemetery just outside the newly organized city limits of Indianapolis. Though it once covered 30 acres, the cemetery suffered from industrial sprawl, flooding, and grave robbing before the city closed it in 1890.

Beginning in 1821, early settlers , , Daniel Shaffer, and Matthias Nowland laid out the first four-acre section of the public cemetery along the east bank of the and present-day Kentucky Avenue. The cemetery, referred to as the Old Graveyard or the Old Burying Ground, was not platted. Families buried their deceased with “graves being dug promiscuously according to the selections made by the friends of the deceased.” It became the final resting place for those buried at public expense as well as for prestigious Hoosiers such as Governor James Whitcomb and Matthias Nowland.

By 1834, the city cleared 6.5 acres of adjacent woods and underbrush off Kentucky Avenue to expand the cemetery east of the Old Burying Ground which they referred to as the New Burying Ground or the Union Cemetery. Unlike the original graveyard, residents , , James Blake, and J.G. Brown modeled the burial ground on the New Haven, Connecticut Cemetery (the Grove Street Cemetery) which featured a grid layout of family lots “with sufficient room between for carriages.” Coe and his associates sold the lots for around $10 each.

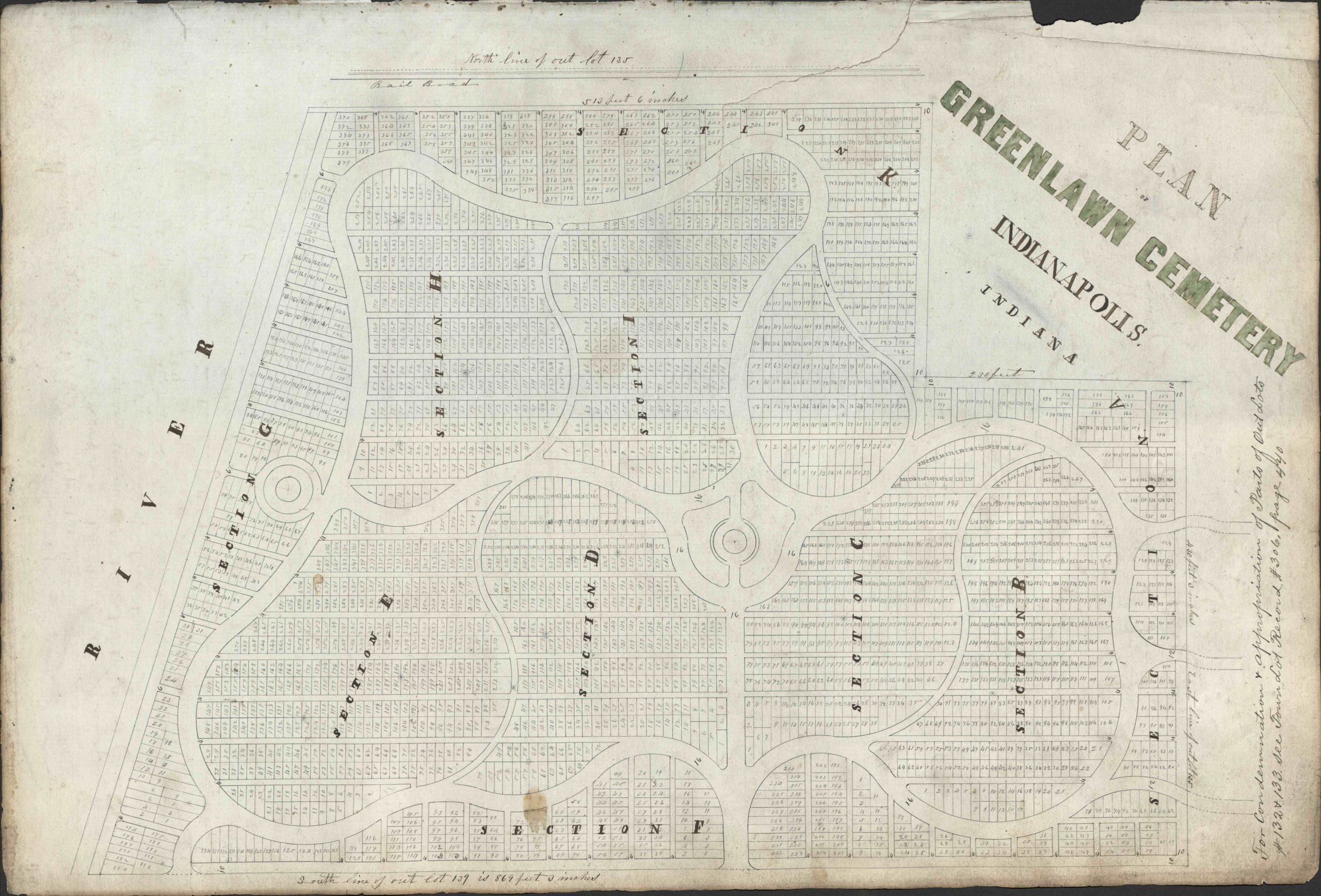

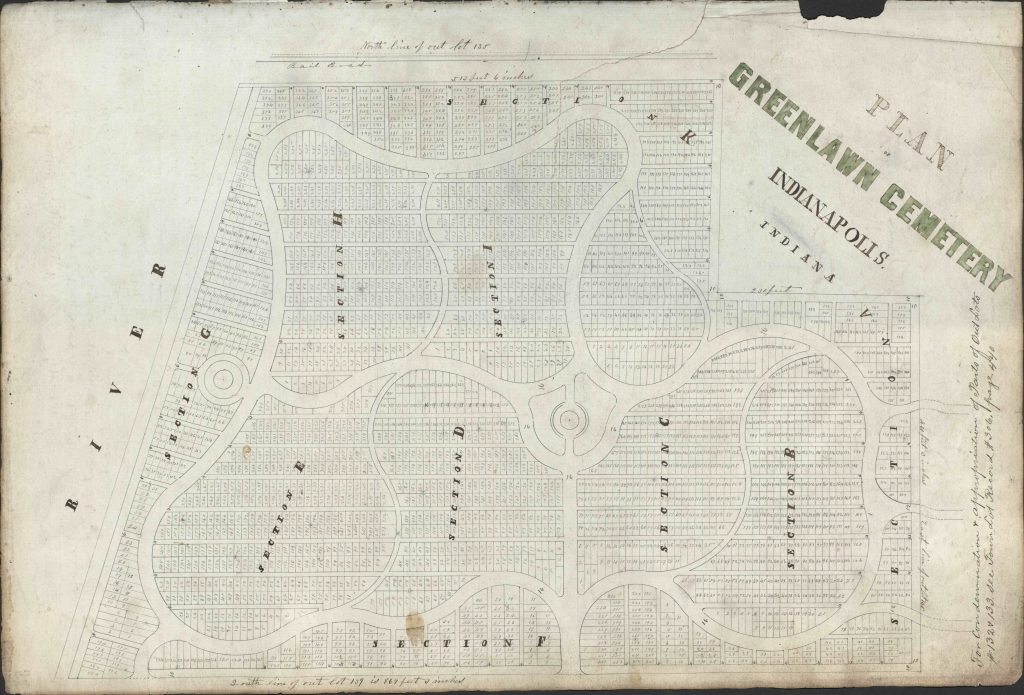

In 1852, Edwin Peck, architect and president of the Terre Haute & Indianapolis Railroad (which merged with numerous other lines to form the Vandalia Railroad—see ) laid out a seven-acre section called the North Burying ground or the Peck Ground, northeast of the Union Cemetery, still along Kentucky Avenue. This section featured 250 lots with tablet-style headstones. John Siter and Richard Price of Philadelphia platted the fifth and final section called the Greenlawn Cemetery in 1860. This section proved the most meticulously designed and landscaped of all five sections of the cemetery.

By the late 1860s and early 1870s, the area around the interconnected cemeteries became increasingly industrial and commercial. The Terre Haute & Indianapolis Railroad increased traffic to the area which contributed to the loss of pastoral serenity. On October 19, 1866, the city initiated a plan to repurpose the cemetery site for business use by relocating the corpses of the Confederate prisoners to section 10 of Crown Hill Cemetery. After the relocation of the prisoners, the railroad used the land to expand its footprint by building a slaughterhouse over a large section of the original Greenlawn cemetery. In 1872, the Terre Haute Railroad built an enormous roundhouse between the railroad tracks and the Old Cemetery. A year later, J.C. Ferguson and Company built a packing house south of the roundhouse. constructed a slaughterhouse north of the roundhouse in 1874.

In addition to the diminishment of Greenlawn in size and stature due to its proximity to an industrializing city, the cemetery suffered from prolific during the 1870s. Local medical colleges lacked a steady supply of corpses for their students to study, which led to the macabre business of stealing corpses from graves at Greenlawn. Equally scandalous, local authorities dismissed the practice for several years.

By this time, many Indianapolis residents no longer viewed Greenlawn as a desirable location for burial. They preferred the new cemeteries that had been built in more pastoral parts of the city, including Catholic and Jewish cemeteries to the south and to the north. The more affluent citizens began relocating the remains of their family members from Greenlawn to other cemeteries, including the descendants of Governor Whitcomb who relocated his remains from Greenlawn to Crown Hill.

While many residents were choosing other cemeteries for their deceased, the city’s policies and practices of segregation forced Black citizens to bury their families west of the original Burying Ground in what was essentially the riverbank. This section suffered flooding and erosion. An account from 1885 recalled that “probably a third of the original area had gone down the river, in some cases leaving portions of skeletons uncovered.”

By the end of the 1880s, Greenlawn had turned into a morbid curiosity for Indianapolis citizens. Local newspapers documented the condition of remains as families exhumed their loved ones for relocation to a new cemetery. Undertakers found it difficult to bury the dead due to overcrowding, and in some cases, the sexton of the cemetery buried corpses in lots belonging to others or multiple corpses in a single lot. The health department fined undertakers whose holding vaults were filled beyond capacity, spewing unpleasant odors. Some bodies had been stored in vaults for 40 years.

In 1890, the city passed an ordinance to prevent burials in Greenlawn, yet the burials continued. The deterioration of the crematorium, the flooding of White River into the cemetery, and the vandalism of tombstones left the cemetery in shambles. The Board of Public Works condemned Greenlawn in 1896 for mismanagement. The city took over the site and converted part of it into a park known as Greenlawn Park. However, the deeds that the city sold for burial lots in the North Burying Ground came with a clause stating that ownership of the lot reverted to the original deed holder if the grounds were no longer used for burial purposes. Thus, in 1909 Edwin Peck’s heirs sued the city and won their battle to reclaim the property.

Peck’s heirs initiated the mass exhumation of bodies in the former North Burying Ground in 1911. They relocated 1,100 bodies to section 226 (then called sections 52 and 52-B) in the north section of Crown Hill Cemetery. This section, known as the Pioneer Cemetery, maintains a single headstone with the names of those exhumed individuals. Around 1913, Peck’s heirs sold the North Burying Ground section to the as an investment property, and by 1917, Diamond Chain started construction of its facility. The company acquired another section of Greenlawn from the city in 1924.

The city sold the New Burying Ground to in 1914. The church then donated the land back to the city for the development of a park. On January 27, 1914, the city broke ground for the Federal League Baseball Park and Grandstand. With seating for 25,000 spectators, the park served as the home field for the short-lived Indianapolis Hoosier Federals, known as the Hoofeds. The team relocated to New Jersey in 1915, and the baseball park and grandstand lay vacant until its demolition in 1917.

In 1916 the Company bought the land where the stadium lay to develop its freight sheds. The company purchased the four-acre parcel of Greenlawn that made up the Old Burying Ground in 1924. It conducted a mass exhumation of the site, relocating 1,800 bodies to Floral Park Cemetery and others to Holy Cross, Cavalry, and Crown Hill cemeteries.

By the time the city excavated part of Greenlawn to build the Kentucky Avenue Bridge in 1925, the marker for the Confederate Soldiers (built in 1910) served as the only remnant left to signify the site’s use as a burial ground. The city moved the marker to in 1929. The removal of the 1,600 Confederate prisoners remaining at Greenlawn to their final resting place at Crown Hill Cemetery occurred in 1931. A third and final exhumation and relocation of Confederate prisoner remains occurred in 1937.

Over the years, the Diamond Chain Company embarked on numerous expansions to its original footprint. Excavation of land resulted in the discovery of bodies that the city failed to exhume during the numerous relocations of corpses from the former Greenlawn to other cemeteries. Diamond Chain Company made these discoveries as late as 1999.

The site was slated in the 2020s for redevelopment into the soccer stadium and commercial district called Eleven Park. However, the project confronted pushback as local historians and city officials determined how to proceed over the portion of Greenlawn dedicated to the early Black residents of Indianapolis. It is unknown how many graves might remain in the ground near the location where the city planned to expand the Kentucky Avenue Bridge. In December 2023, the Keystone Group, developers of Eleven Park, confirmed that “fragments of human remains” were discovered on the site of the old Diamond Chain plant along the White River.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.