Early medical schools, such as the Indiana Medical College and the Central College of Physicians and Surgeons, were freestanding, private institutions (see ). In the decades following the Civil War in the U.S., the medical education that took place in these private proprietary schools shifted from rote memorization to clinical-style learning based on a European model. Dissection of cadavers was central to this evidence-based education.

To instruct students in clinical-based dissection, medical schools required cadavers. Existing laws made the legal procurement of corpses difficult. A shortage of cadavers opened the door to an underground business of grave robbers, who surveyed cemeteries by day and dug up fresh bodies by night. These body snatchers supplied corpses to local medical institutions. Body snatching became even more lucrative after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, which facilitated the movement of corpses across the country.

For the right price, ministers and funeral directors tipped off grave-robbing gangs of upcoming burials and promised to look the other way. Some medical schools paid these grave robbers $35 per body. Since most gangs could break into graves in as little as 25 minutes, they could earn a handsome sum for one night’s work.

The nationwide phenomenon of grave robbing did not escape Central Indiana. To deter grave robbers, some individuals resorted to burying their loved ones with explosives, known as grave torpedoes, next to grave sites. Other families hired night watchmen, stood vigil next to grave sites themselves, or built cages around graves all to prevent grave robbing.

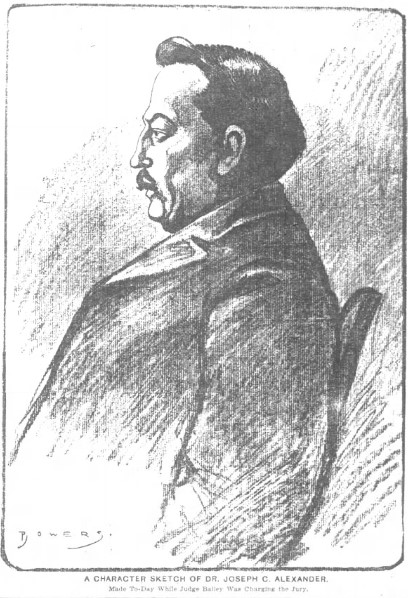

The Central College of Physicians and Surgeons and other medical schools in Indianapolis were involved in a notorious grave-robbing scandal that came to light in 1902. Central College of Physicians and Surgeons had purportedly been involved in an incident of body snatching dating to 1898. Another incident the Indiana Police Department was investigating dated to October 1901. But in September 1902,?Dr. Joseph C. Alexander, a native of who served as director of the anatomical laboratory charged with the procurement of cadavers for medical students to dissect, was implicated along with Rufus Cantrell in an Indianapolis Police Department (see ) investigation that revealed an underlying grave robbing scheme. An Indianapolis gunsmith sought to recover shotguns purchased with partial purchase but later pawned. Alexander was the guarantor for the payment, and Cantrell was one of the purchasers.

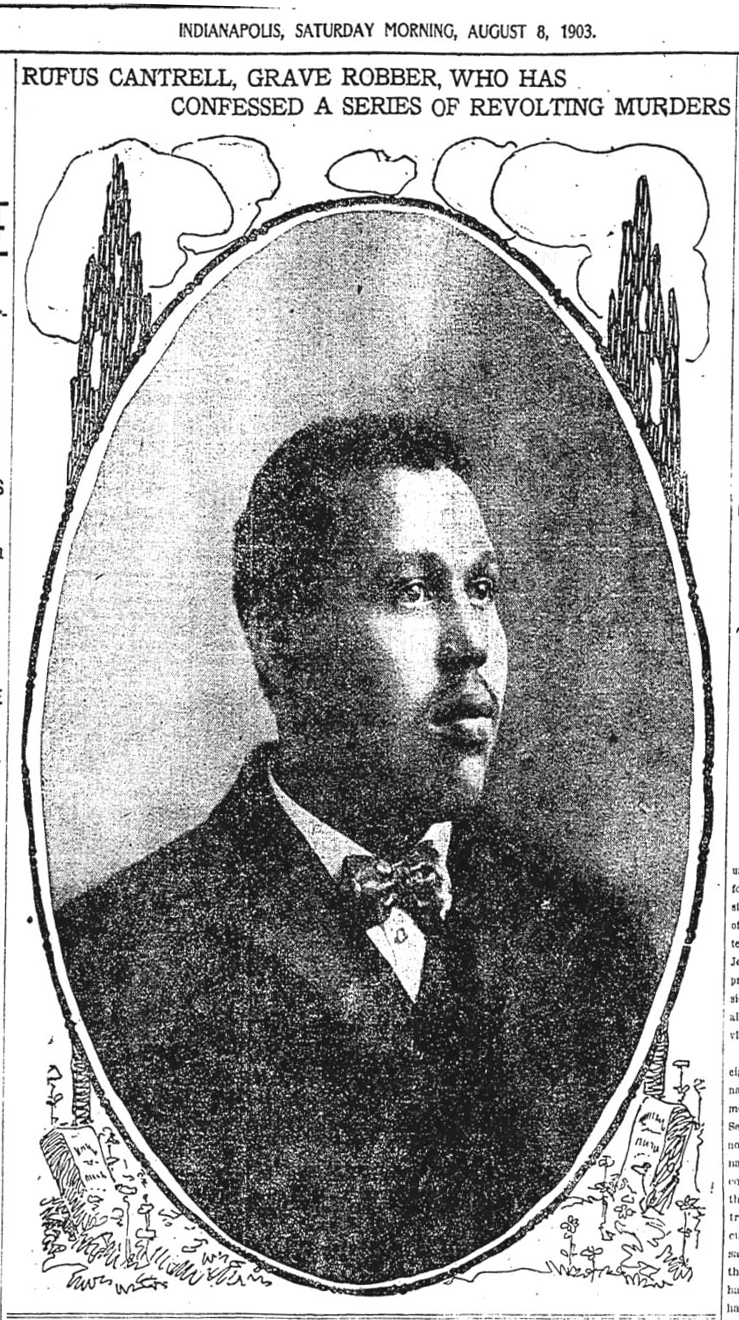

The police arrested Cantrell, and when he was questioned, he implicated Alexander and other doctors in grave robbing. Cantrell alleged that Alexander paid him $30 per body. Alexander purportedly accompanied Cantrell and his gang during body-snatching excursions. Cantrell claimed to have robbed hundreds of graves in and surrounding counties, with most bodies stolen in Hamilton County. The shotguns provided protection in case Cantrell and his gang were discovered during the body snatching.

Though Alexander denied involvement in the scheme, he was arrested and charged with disturbing a grave, taking a corpse, and aiding in the concealment of a corpse. A grand jury returned 25 indictments against Alexander and four other physicians from other medical schools on October 26, 1902.

Alexander’s trial started on February 2, 1903. Marion County Prosecutor John C. Ruckleshaus prosecuted the defendants. Ruckleshaus charged Alexander with violation of an existing law that mandated recordkeeping of all bodies taken for dissection. The violation was punishable with a fine of $100 and $500 and one to five years in jail. Though Cantrell was the star witness during the trial, the true damage to Alexander’s case came from pawnbrokers and merchants who had received in-person payments from Alexander for items Cantrell brought to the trial as evidence. The trial ended in a hung jury. Ruckleshaus dropped the charges on April 11, 1903, and Alexander was released. He reopened his practice in 1915 and died 10 years later.

Rufus Cantrell, an African American, stood trial on April 20, 1903. He pled insanity but was convicted of grave robbing. Race most likely played a factor in his prosecution. The jury recommended a sentence of 2 to 14 years in the state prison in Jeffersonville, Indiana.

However, when Rufus Cantrell was arrested in September 1902 for the grave-robbing scheme, he fingered Wade Hampton “Hamp” West as his main competitor in Hamilton County. West, a native of North Carolina, came to Hamilton County around 1880.

Cantrell identified West as the kingpin who controlled grave robbing in Hamilton County. Cantrell claimed that he and his gang received West’s permission to steal the body of Newton Bracken from the Beaver Cemetery, now known as Highland Cemetery, in September 1901. When West rescinded his offer, a shootout between the two gangs ensued, leaving William Gray of Cantrell’s gang dead. Cantrell claimed Gray’s body was disposed of, while West claimed Gray was alive. Gray’s body was never recovered, however, West delivered Bracken’s corpse to the Central College of Physicians and Surgeons.

West was arrested for grave robbing and the murder of Gray on November 14, 1902. Though prosecutor W. R. Fertig dropped the murder charge for lack of evidence, he tried West for grave robbing.

A grand jury indicted West in March 1903. West’s trial began in on July 2, 1903. One of the last witnesses the prosecutor produced was a neighbor of West’s. This gentleman claimed to have seen West boiling a headless heavyset man in a kettle on West’s property. West denied the incident, and the judge did not admit the testimony based on its irrelevance to the crime at hand. Still, on July 16, a jury found West guilty of grave robbing. He was sentenced to 10 years at the Michigan City Penitentiary, where he died of stomach cancer the following year.

Cantrell was paroled in 1909 after serving six years of his sentence. He moved to Anderson. Here, he attempted to capitalize on his infamous crimes by turning them into a stage show. In 1915, he moved to Michigan and became a preacher. He landed in the Marquette State House of Correction for two years after parishioners accused him of stealing. He was paroled in 1918 and disappeared from the records.

Despite the gruesome nature of grave robbing, the episode led to positive change in the procurement of cadavers for medical schools. In 1903, the Indiana General Assembly passed House Bill 100, creating the State Anatomical Board to oversee the distribution of cadavers to medical schools. Today the oversees the State Anatomical Board. A historical marker stands in Fishers in front of the Fall Creek Township Trustee’s office to commemorate the law.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.