Photo info …

Credit: Mike Serpa via Find A GraveView Source

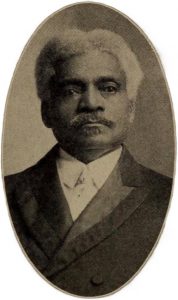

(Sept. 16, 1841-Aug. 24, 1927). African American publisher George L. Knox embodied Booker T. Washington’s values of economic uplift and self-reliance. Born an enslaved person in Tennessee, he came to Indiana in 1864 when a Hoosier officer in whose Civil War regiment Knox served as a runaway was furloughed.

Learning the barber’s trade, he opened a shop in in 1865—the same year he married. Highly successful, he became a prominent Republican and an organizer of the town’s first Black Methodist congregation, public school, and Sunday school. He also became friends with .

By the time Knox moved to Indianapolis in 1884, he had established patterns of business and civic values that characterized the remainder of his life. By the mid-1890s, he owned a number of barbershops and had 50 employees. Knox gained substantial income and secured the friendship of prominent whites, chiefly .

Holder of the mortgages, he purchased the paper in 1892 and made it a mouthpiece for Harrison. He was a delegate to in 1892 and 1896. Beginning in December 1894, his paper published a series that became his remarkable autobiography, (1895), the appearance of which supported the message that Booker T. Washington gave at the Atlanta Exposition that same year. Knox’s economic progress achieved through hard work along with the strong relationships he developed with whites seemed to exemplify what Washington argued for as the basis for the advancement of African Americans in his famous speech.

With the Republican abandonment of Blacks, however, Knox retreated from political activism. At first, he supported national Republicans and independents at the state and local levels but eventually endorsed the national Democratic ticket. He espoused Booker T. Washington’s economic message of self-help, although in later years he also supported the . Most consistent was his devotion to Methodist church programs.

After his first wife’s death in 1910, Knox remarried and his only surviving child, Elwood, took over managing the . The paper fell on hard times, however, and filed for bankruptcy in 1926. George Knox was promoting Black newspapers in Richmond, Virginia, when he suffered a stroke. He never abandoned his hopes for the advancement of African Americans. He is buried in .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.