Fresh Air Schools (FAS), or open-air schools, were initiatives of the Indiana State Board of Health, the Indiana Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, and the Marion County Tuberculosis Association (see ) to address the growing public health concerns of children afflicted with anemia, undernourishment, and pre-tuberculosis symptoms in Indiana. The Marion County Tuberculosis Association worked with the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners to establish classrooms and entire schools that followed the FAS model. Seven public schools in Indianapolis, all racially segregated, were opened from 1913 to 1929 to combat these public health concerns using FAS principles, though unsanctioned experimentation with the concept started in 1911.

The Fresh Air or Open Air schooling movement began in Germany in 1904. The movement emphasized good nutrition, physical activity, fresh air, and rest periods as ways to improve the health of children suffering from anemia, cardiac issues, and pre-tuberculosis symptoms. Participating schools aimed to renew children’s physical health while educating them in a restorative environment. In the United States, the first FAS opened in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1908. The concept arrived in Indianapolis in the early 1910s.

Without support or funding from the school system or board of health, Estella Adams, a teacher at (IPS) No. 57, became the first to experiment with the open-air concept locally. Over the winter of 1911–1912, she deliberately left her classroom windows open, which kept the room’s temperature between 62 and 64 degrees Fahrenheit. She found that her students seemed to have less sickness than the average for their grade level. During the spring, Adams successfully petitioned the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners for desks and chairs to be placed outdoors, allowing her to continue and expand her fresh-air teaching experiment.

After deeming Adams’s innovation a success, the Indiana Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis in 1913 sponsored the first local classrooms following the FAS model. These were at the all-white Lucretia Mott IPS No. 3. Over subsequent years, accommodation was made for other public-school classrooms to follow the fresh-air principles.

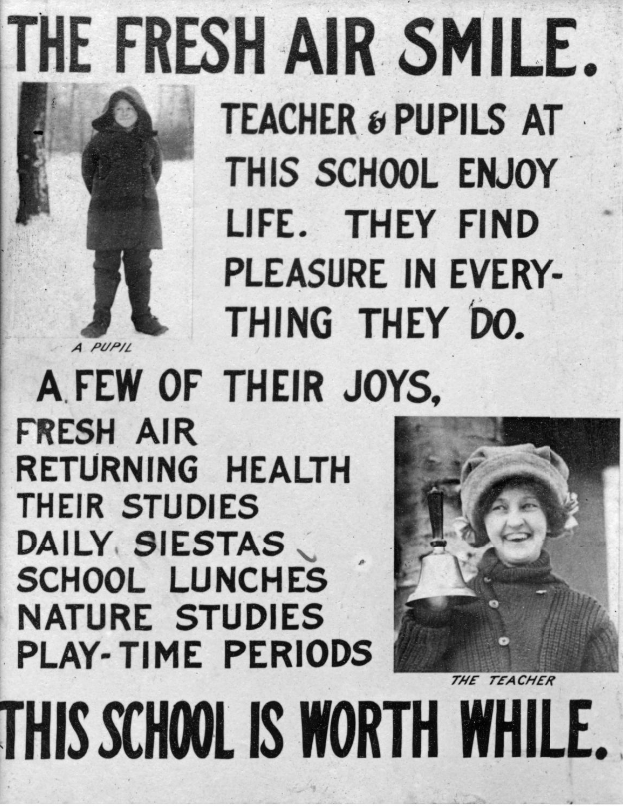

Three types of FAS’s existed, though only two of these were found in Indianapolis. One type, called the open-window classroom, used standard indoor classrooms but mandated that every window remain open. A variation, called the muslin-screen classroom, employed specially built screens of cloth, inserted in the lower half of windowpanes, in order to allow outdoor air penetration while reducing incoming wind, soot, and debris. The third type, which was not employed in Indianapolis, called for the entire school population to conduct education fully outdoors. All three approaches had no in-room heat source. During the winter months, the temperature of most rooms was 62–64 degrees Fahrenheit. In colder weather, hooded garments, called “Eskimo suits” by teachers and children, were made from surplus army blankets to keep participating children warm. Extending the fresh-air principles, some classes had a sleeping porch for the required 1 ½-hour rest period that the FAS model mandated for “infirm” children.

FAS classrooms in Indianapolis, each with a capacity of 20–30 children at maximum, were populated with students who were considered at risk of developing tuberculosis due to existing conditions such as anemia, undernourishment, or possible exposure to the disease at home. Healthy children or ones with other kinds of infections were not eligible for enrollment. The approach’s success rate was measured not only by improvements in participating children’s health but also in their academic growth. Children were regularly weighed to measure the effectiveness of nutritious meals and snacks. Since many of the students were from poor families, the cost of meals was often borne by charitable organizations. In determining eligibility for fresh-air classrooms, the district categorized students as medically “normal,” “subnormal,” or “anemic,” with the special classrooms generally (though not exclusively) reserved for the students in the latter two groups.

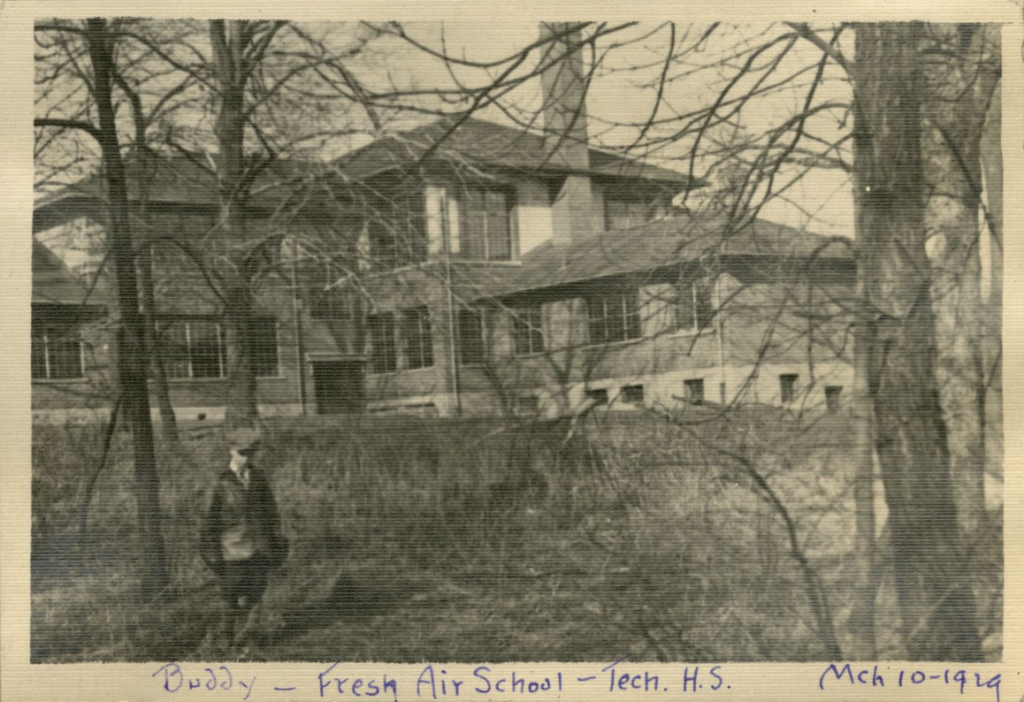

Indianapolis’s lone example of an entire school, rather than a few dedicated classrooms, using the FAS model was the all-white IPS No. 74, opened in October 1914. Founded with the encouragement of Indianapolis physician , it was located in the neighborhood on the grounds of (formerly the ). Called the Holliday Outing School, it began operations near the high school gymnasium in a former training shop, referred to as “the shack,” with room for 25 children. The school was moved to the northeast corner of the high school grounds and renamed the Theodore Potter Fresh Air School in 1924 after a new building was erected with a capacity for 120 students.

In 1917, two more fresh-air schoolrooms, using either the open-window or muslin-screen concept, opened in Indianapolis: one at the all-white Robert Dale Owen IPS No. 12, and one for African American children at IPS No. 24, the School. By 1929, two more schools opened using fresh-air schoolrooms: the Open Air School No. 22 and the . During this period, the Indianapolis Public Schools were rigidly segregated by race, and the fresh-air teaching locations followed this pattern, with all of these schools and classrooms reserved for whites except those at IPS Nos. 24 and 26.

By World War II, the need for Fresh Air Schools significantly decreased due mainly to the development of early antibiotics such as isoniazid that could treat and prevent tuberculosis. Furthermore, education policy shifted from the open-air model to modern buildings with temperature-controlled classrooms. Even so, Theodore Potter IPS No. 74 continued as a fresh-air school into the 1950s.

FURTHER READING

- Indiana State Library. “Open Air Schools in Indiana.” December 2, 2020. https://www.in.gov/library/site-index/open-air-schools-in-indiana/.

- Marion County Tuberculosis Association. “Reports on Fresh Air Schools in Marion County Beginning 1913.” Indiana Historical Society. https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/tuberculosi/id/142/rec/15.

- The Open Air School Movement in Indiana. Indiana State Board of Health, 1918. https://indianamemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16066coll52/id/9137/.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Erickson, N. (2025). Fresh Air Schools. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 7, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/fresh-air-schools/.

MLA:

Erickson, Norma. “Fresh Air Schools.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025, https://indyencyclopedia.org/fresh-air-schools/. Accessed 7 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Erickson, Norma. “Fresh Air Schools.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025. Accessed Mar 7, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/fresh-air-schools/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.