Freethought aims to approach all matters objectively and rationally, although this definition oversimplifies. Principally antireligious, thus its atheistic and humanistic cast, the movement encompasses a wide range of thinkers and doers: social activists, radicals, iconoclasts, liberal religionists, and ideologues. Their ideas and activities often have, in time, become public policy.

Freethought came to the United States through English Deism and German Rationalism, the latter being particularly relevant in Indianapolis. The large German component in Indianapolis in the mid-to-late-19th century practically guaranteed the presence of freethought.

Although some freethought stirrings occurred before 1870 (the , Indianapolis, 1853-1866, is considered a freethought newspaper), the organization in that year of the Indianapolis Freidenker-Verein or Freethinkers’ Society is generally recognized as the origin of freethought in the city. This group, led by , , and , sought to instill progressive and modern ideas in their children and their community.

Indianapolis freethinkers instituted lectures, a “Sunday School,” and social programs, and they challenged conventional wisdom through their advocacy of women’s rights, health insurance, and vocational education. Clemens Vonnegut’s , published in 1889, is a freethought tract from this era.

Through its 20-year existence, membership in the Freidenker-Verein never exceeded 80. The group faded in the 1880s from lack of volunteer effort and funding, and it disbanded in 1890.

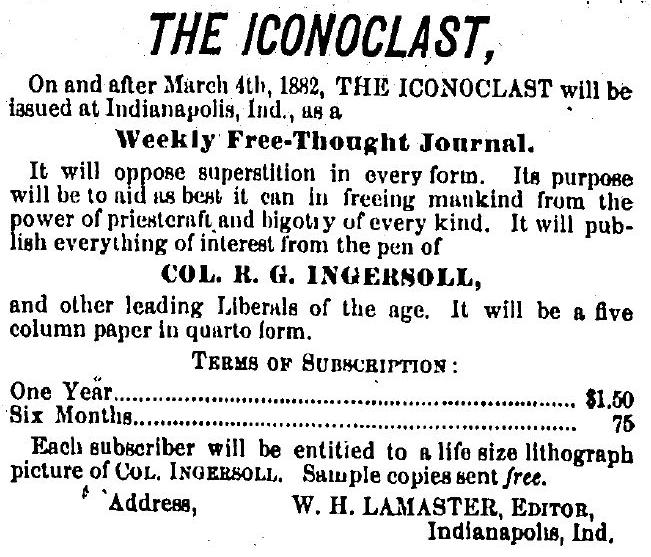

Organized freethought in Indianapolis stalled after the collapse of the German society. Indianapolis weeklies such as and Dr. Jasper Roland Monroe’s Indianapolis weekly , advocated freethought issues in the 1890s, but most freethinkers wanting an organizational structure had to go out of state.

In 1909, however, Indianapolis hosted the first convention of the newly formed Indiana Rationalist Association. This group established its headquarters in Indianapolis and many of its officers and members came from the capital city. In 1911, it published an important compilation of its activity entitled . Its purpose was almost exclusively antireligious: it sought to expose the fallacy of revealed religion, oppose the union of church and state, and disprove the existence of the supernatural.

A leading spokesperson was Dr. James A. Houser, an Indianapolis physician, who lectured widely and disseminated his orthodoxy, called the New Science of Life. A lack of dues-paying members spelled the end in 1913 for the Indiana Rationalist Association, which then evolved into a national body, though not headquartered in Indianapolis.

A few short-lived groups, the Truth Seekers, the Scientific Educational Society, and others attempted to carry on the work, but organized freethought in Indianapolis for all practical purposes ceased by the mid-1920s. Individuals, afterward, practiced freethinking with memberships in national or regional humanistic and atheistic bodies.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.