The biological landscape of Indianapolis is a product of both postglacial climatic change and human activity, set in the varied terrain left by the last ice sheet. Although plant and animal patterns may seem static at human timescales, they have been and still are changing in response to changes in natural and human environment.

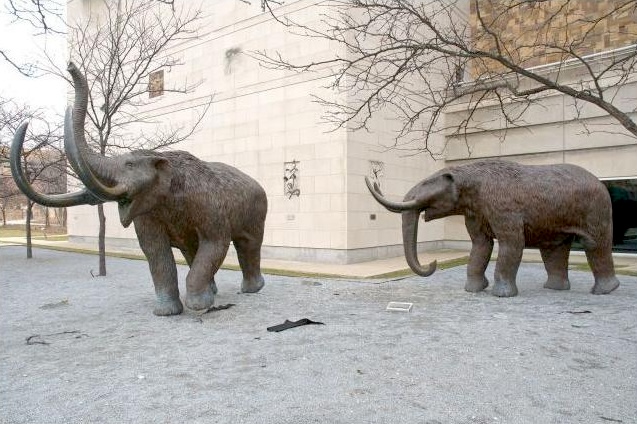

The history of the present landscape began less than 20,000 years ago, with the retreat of the Wisconsin ice sheet from its terminus just south of present-day Indianapolis. Fossil pollen from midwestern lakes and bogs suggests that tundra, spruce woodland, and spruce forest invaded rapidly in the glacier’s wake. These plant communities apparently supported diverse assemblages of large mammals, including northern species such as white-tailed deer; and species now extinct, such as mastodon and giant beaver.

By 10,000 years ago conifers were being replaced by many of the broadleaved trees of the present deciduous forest, including oaks, hickories, elms, ashes, and maples. The deciduous forest did not arrive as a unit, as once thought, but species by species from various directions. For example, the sugar maple may have reached central Indiana from the south by about 10,000 years ago, but beech arrived from the east some 4,000 years later. Thus, the beech-maple forests of central Indiana are not more than a few thousand years old, and some scientists have argued that they are still changing in response to postglacial climate change.

The accompanying animal migrations are less well documented, but most evidence suggests that mammal communities have become less diverse since early postglacial time. This decline was due partly to emigration of species still extant elsewhere, such as the caribou, but many large mammals (including the mastodon and giant beaver) became entirely extinct around 10,000 years ago. Central Indiana animal communities are thus also recent assemblages.

People arrived early in this story, but little is known about their effects on biological patterns in prehistory. Some paleontologists believe that early hunters caused the large mammal extinctions just mentioned, though others attribute their demise to natural climate change. are known to have set fires in some midwestern forests, but there is little record of human-set fire in central Indiana, perhaps because many forests stayed too wet to burn.

It is known that Amerindian agricultural groups introduced crops (maize, beans, squash, Indian tobacco) and weeds (annual sunflower) from tropical America and western North America, and that they cleared patches of bottomland forest around villages for cropland. When the first whites arrived, one Delaware town at the southern edge of Marion County reportedly was cultivating fields on the floodplain. Such clearings, however, were a minor part of the total landscape, and the introduced crops and weeds may have remained closely confined to village sites.

White settlers thus entered a landscape that, while not pristine, was still almost entirely forested. The 1819 General Land Office survey, which provides a systematic sample of Marion County vegetation just before settlement, shows forest broken only by scattered brushy openings, streams, and swamps. There were apparently no prairies, though open wetlands such as contained some wet-prairie plants.

Upland forests were predominantly beech-maple communities: more than half of all trees in the 1819 survey were American beech or sugar maple. Many other species were present, including white and green ashes, Ohio buckeye, black walnut, American and slippery elms, shagbark and bitternut hickories, and several oaks. Black cherry, sassafras, and other fast-growing trees of forest openings were uncommon, judging from their rarity in the survey.

Forest composition varied with local topography. The 1819 witness-tree patterns and remaining forest stands in and around Marion County suggest that swamp white oak, bur oak, hackberry, and other wet-site trees were important around seasonally flooded upland depressions. White oak, chinquapin oak, and the hickories were prominent on dry hills and ridges, such as those west of . The floodplain forests of White River and other large streams comprised a distinctive suite of fast-growing, disturbance-tolerant trees: eastern cottonwood, silver maple, black willow, sycamore, and box elder.

The General Land Office survey did not describe animal patterns, but we can infer that the terrestrial animals were mostly forest species. Many of these would have been characteristic of closed forest, including bobcat, timber wolf, black bear, turkey, ruffed grouse, and passenger pigeon. In , Indianapolis pioneer Oliver Johnson recalls shooting wild turkeys at the edge of the family cornfield and helping tree a bear near the present state fairgrounds. There would also have been species characteristic of forest edges and openings, such as opossum, fox squirrel, rabbit, and goldfinch. Rivers and other wetlands provided habitat for waterfowl, turtles, muskrat, beaver, and other wetland species.

Biological patterns may not have been in equilibrium when whites arrived, but white settlement dramatically increased the pace and scope of biological change. The most drastic change was forest clearing. Historical surveys indicate that forest cover was reduced to about 40 percent of Marion County by 1876, 10 percent by 1952, and perhaps 1 percent by 1986.

These surveys underestimate the extent of tree cover (for example, they ignore urban trees), but they confirm the near-complete elimination of the original forest. What remain are mostly scattered farm woodlots around the edge of the county and narrow streamside corridors on land too steep or wet to farm. None of these stands has escaped alteration by logging, grazing, Dutch elm disease (introduced from Europe in the 1930s), the accidental introduction of the emerald ash borer (indigenous to China) in the early 2000s, or other human influences.

Most woodlots are dense, young secondary forest with, at most, only scattered old trees, and their composition has changed with cutting of oak and black walnut and increases in “weed” trees such as hawthorn, black locust, and redbud. The best remaining examples of what pre-settlement forests might have looked like are found in small stands at and in four small nature preserves: Eagle’s Crest, Spring Pond, Marott Park, and .

Settlers soon eliminated most of the large mammals native to Marion County including the timber wolf, black bear, bison, bobcat, white-tailed deer, and beaver. Many of these animals were hunted even before settlement and disappeared before 1850. Deer and beaver have been successfully reintroduced, but the large predators have not.

Several prominent birds were also eliminated fairly early: the ruffed grouse, turkey, Carolina parakeet, and passenger pigeon. Although hunting is now restricted, some small animals may still be disappearing because of habitat loss. For example, the continued decline of small migratory songbirds in the Midwest has been linked to fragmentation of the forest into small, isolated islands with little or no deep-forest breeding habitat. Climate change will also have some effect on the patterns of migratory birds.

Loss of forests and of wetlands such as Bacon’s Swamp has greatly reduced the abundance of many plant species, though few are known to have been entirely eliminated. The most conspicuous local plant extinction is an inconspicuous trailing herb named running buffalo clover, a plant apparently closely associated with bison trails.

The pre-settlement forests have been replaced by fields, pastures, parks, vacant lots, lawns, and gardens. These herbaceous communities are human-created and human-maintained, prevented from returning to forest by continual expenditure of human energy. They are also ecologically open communities, with dry, sunny microclimates and biological interactions continually disrupted by human disturbance. By all of these measures, they are less stable than the forests they replaced. While forest cover has increased in Indiana since the 1960s, Indianapolis has not experienced much forest growth over the last several decades.

Alien plants and animals commonly dominate these new communities. Most of our important crop plants and livestock animals, most lawn and forage plants, and probably most ornamentals and weeds are Old World species introduced, intentionally or accidentally, since settlement. Although some remain under human control, many have become naturalized and are now easily mistaken for natives. The starling, house sparrow, honeybee, Queen Anne’s lace, and Kentucky bluegrass (native to Europe, not Kentucky) are conspicuous examples from a long list. As botanist Edgar Anderson put it, we are surrounded by “transported landscapes”. Native plants and animals have also moved into all of these communities, but they are mostly species of open, disturbed habitats, not closed forest. Some (chipmunk, opossum, giant ragweed) were probably present in naturally open sites when white settlers arrived. Others have invaded since settlement, often from the prairie region to the west (coyote, brown-headed cowbird, windmill grass).

It is not clear how historical invasion and extinction have affected overall biological diversity. Plant diversity has likely increased, whereas mammal and bird diversity may have declined. Regardless, this biological turnover has created a more generic biological landscape of widespread weedy species. Homogenization will probably continue as urbanization encroaches on the remaining woodlots and wetlands and agriculture becomes ever more narrowly focused on uniform crops and clean fields.

In 1992, the Office of Land Stewardship was created in the to protect and preserve native wildlife and plant habitats. The office began with less than 50 acres. That acreage has increased over time to 1,700, across 37 properties. The office also educates the public about the value of natural areas and biodiversity. Due to the efforts of the Office of Land Stewardship, Indianapolis was named a National Wildlife Federation Top 10 City for Wildlife in 2015.

In the 21st century, climate change is expected to result in wide-ranging changes in the biological environment, with average temperatures predicted to rise by 4 degrees Fahrenheit (2.2 degrees Celsius) relative to preindustrial levels.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.