The first recorded fire in Indianapolis occurred on January 17, 1825, when Thomas Carter’s tavern burned to the ground. There was no fire department, but citizens rallied around the frame building opposite the courthouse on Washington Street and managed to save most of the furniture and stock. The disaster persuaded the city to organize its first volunteer fire department in 1826. Since that time Indianapolis firefighters have faced numerous major fires.

Kingan and Company, May 22, 1865

The fire, which completely destroyed the five-story pork packing plant, was the worst in the city’s history to that time, causing over $200,000 in damages. The building was less than two years old and was equipped with the newest slaughtering and packing machinery. Thousands of pounds of pork and lard fed the flames, producing a heat so intense that firemen could hardly approach the building. They quickly abandoned the fire itself and concentrated their efforts on the surrounding buildings. Soaking these buildings prevented the fire from spreading; it finally died sometime after midnight. A subsequent investigation revealed that the building had been thoroughly cleaned of all shavings and flammable materials the day of the fire and, there having been no fire in the plant that day, the fire marshal concluded that it must have been an act of arson. However, owners could name no suspects and the fire’s origin remained a mystery.

Kingan was one of the city’s largest employers and several leading citizens had large quantities of pork and lard stored there. Initial reports indicated that the building, owned by a group of Irish-American businessmen, was not insured and there was concern as to whether or not the company would be able to rebuild. But two days after the fire Kingans owners met in Indianapolis and announced that all but $20,000 of the damages were covered and that they intended to rebuild immediately.

Woodburn Sarven Wheel Company, March 11, 1873

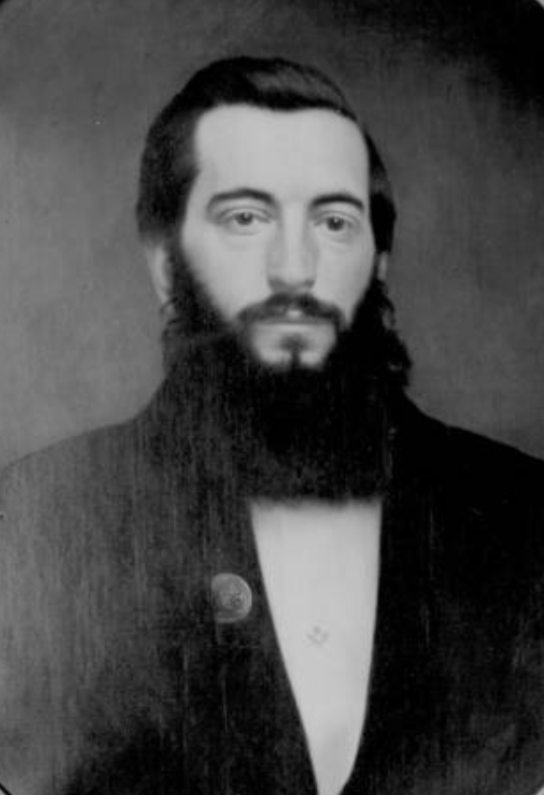

was a wooden wagon wheel factory located south of downtown at the corner of Illinois and Garden streets. The fire started in the machinery room, a large addition at the back of the building, when wood shavings scattered on the floor ignited. It spread quickly through the addition and a party of hose men led by fire chief approached it from the second floor of the original building. While they were there, the firewall of the addition fell onto the roof of the original building, killing Glazier and injuring four of his men. By the time firemen brought it under control at 1:30 A.M., the fire had caused $75,000 of damage.

Chief Glazier’s death was the ‘s first fatality in the line of duty and his funeral was one of the largest in the city to that time. Glazier, along with several of his brothers, had been a prominent member of the paid fire department since its founding in 1859. Among his survivors were several nephews and two sons who were also members of the department. One of the nephews, Ulysses Glazier, died while fighting the Bowen-Merrill fire in 1890.

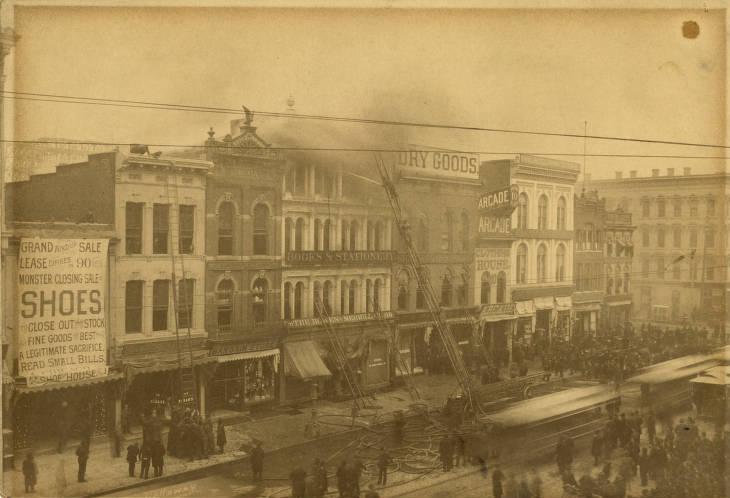

South Meridian Street, January 13, 1888

This fire began at 11 P.M. in the four-story D. P. Erwin dry goods building on the east side of Meridian Street south of Georgia Street. The flames spread quickly and the fire department, hampered by freezing temperatures, was unable to contain them. The fire moved north to Stout’s wholesale grocery house, then crossed the street and consumed Pearson & Wetzell’s queensware house. By the time firemen brought the blaze under control at 3 A.M., it had destroyed six buildings on either side of Meridian in the . The loss of these buildings and damages to two others amounted to $1 million, making it the worst fire in the city to that date. Heat from the fire was so intense that much of the hose laid on Meridian Street was scorched and ruined. Unable to use ladders to reach the buildings’ upper floors, firemen were forced to approach from the rear of the buildings. Much of their clothing was scorched, but no firemen were injured.

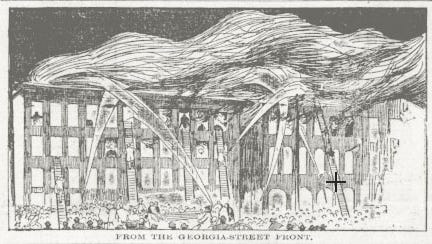

Bowen-Merrill, March 17, 1890

At 3 P.M., employees of the Bookstore at 18 West Washington Street noticed smoke coming from the iron gratings in the sidewalk in front of the store and notified the fire department. Firemen arriving at the scene found nothing but a smoldering blaze confined to the basement, surveyed the building, and, thinking that things were under control, dispersed the crowd that had gathered out front. Owing to the flammable contents of the four-story building, firemen remained at the scene. At 5 P.M. they detected flames coming from the windows of the upper floors. They quickly doused them with a hose line and believed that they had brought the fire under control. But the building’s cast-iron facade had been hiding a growing fire from firemen stationed on the street and on the roofs of neighboring buildings.

Without warning, all four floors collapsed and over 20 firemen fell into the flames from their post on the roof of the adjacent Becker Building. Rescue and cleanup activities over the next 20 hours uncovered the bodies of 12 firemen. Over a dozen others were seriously hurt, and one died in the hospital from injuries received in the fall. The fire represents the highest death count in the fire department’s history and the fourth-worst disaster in terms of loss of life in Indianapolis’ history

The city rallied to aid the injured firemen and the families of those who perished. On March 18, Mayor appointed a committee of seven, including and former Mayor , to receive funds and take charge of disbursements. As word of the tragedy spread, donations poured in from across the nation. By 1900, the fund had grown to $52,000. It purchased annuities for the 9 widows and 22 orphans, bought homes for 4 of the widows, and paid all funeral and medical expenses. The tragedy spurred the state legislature to create the first statewide pension fund in 1891.

Surgical lnstitute, January 21, 1892

Shortly before midnight, a janitor at Dr. H. R. Allen’s noticed smoke corning from a secretary’s office on the third floor. The institute building, located at the northeast corner of Illinois and Georgia streets, included the upper floors of several old buildings connected by narrow passageways. It was later discovered that the fire had started in an office on the ground floor and quickly spread to the upper floors. Over 300 people were in the building when the fire started, and by the time firemen arrived on the scene 194 patients were trapped on the top floor. With the help of firemen and volunteers, over 250 persons escaped the building unharmed. But many of the patients, mostly invalids and children, remained trapped on the top floor. Some died in desperate leaps from windows, while others died of smoke inhalation or were crushed when a section of the roof collapsed. In all, 19 patients were killed and 50 injured making the fire the city’s third most fatal disaster.

The tragedy at the Surgical Institute did more to stir public interest in building safety than any other fire in the city’s history. The building inspector had condemned the structure as a fire hazard in 1878, but few renovations had been made to meet the prescribed safety requirements. Indianapolis newspapers criticized the city government, the building inspector, and the fire department for allowing the institute to operate in violation of the safety codes. Public outcry spurred reform of the building code and the fire department.

Meridian and Louisiana Streets, February 19, 1905

Fire broke out just before 10 P.M. in Fahnley and McCrea’s wholesale millinery house on South Meridian Street. Fueled by gas from several machines that the firm used to curl feathers, the fire quickly spread through the quarter square bounded by an alley and Meridian, Louisiana, and McCrea streets. Within 15 minutes the fire was so hot that firemen began dousing buildings across the street to prevent its spread. Despite these efforts, the fire moved north, abetted by the electrical wires that connected the buildings. Flames eventually reached the druggists’ sundries and holiday goods house of the E. C. Dolmetsch Co., which had a large quantity of fireworks in stock. Their explosion, combined with explosive drugs from Keifer’s drug store to the south, gave spectators the impression of battle artillery. The fire caused a then-record $1.2 million of damage, but there were no deaths or injuries. The newspapers praised the fire department’s work in controlling the fire and attributed its spread and severity to the presence of gas and electrical wires rather than to the condition of the buildings.

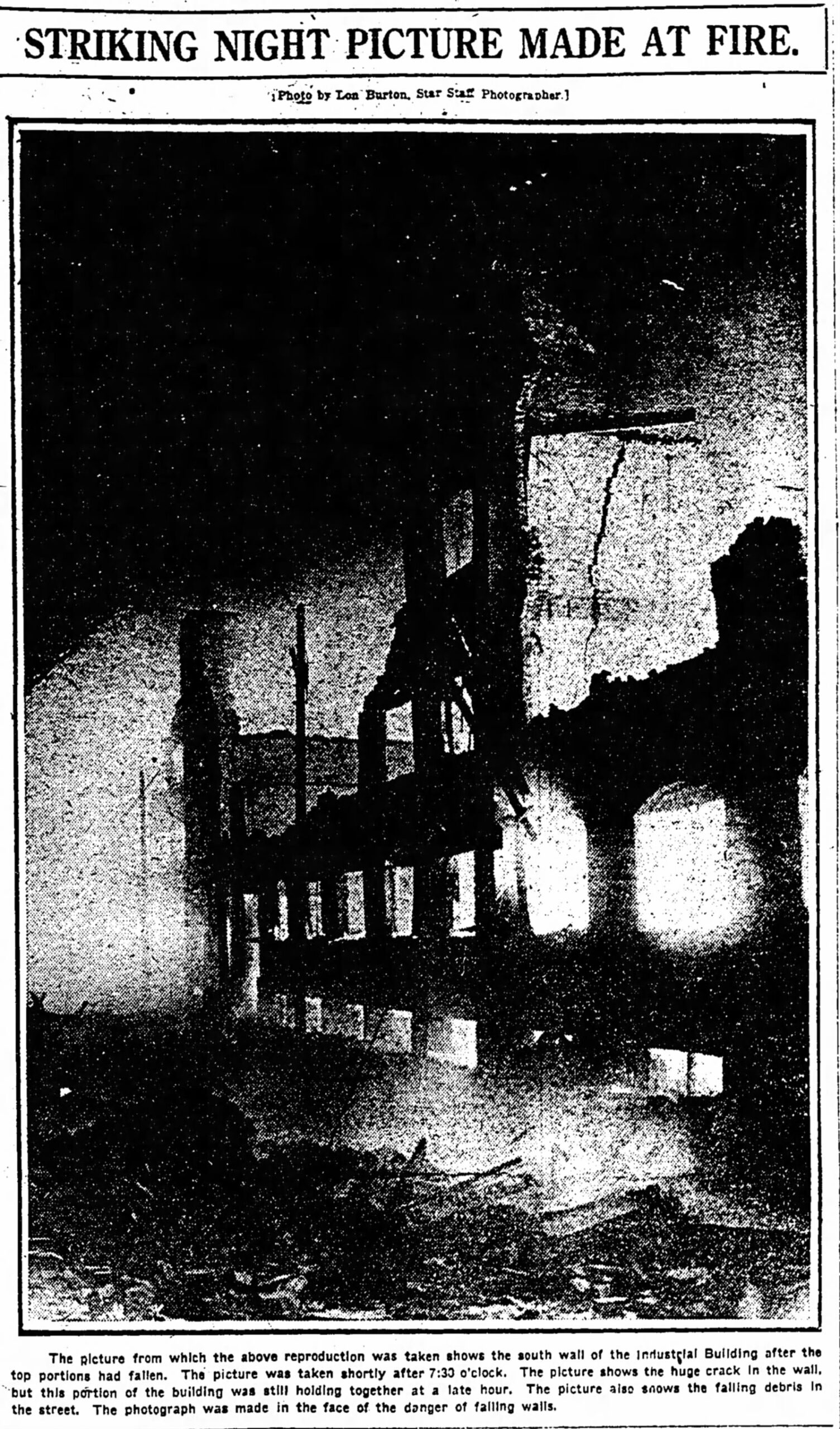

Industrial Building, January 13, 1918

In 1918, the Industrial Building was a 10-year-old, five-story brick, stone, and cement structure containing over 400,000 square feet of floor space. It covered almost the entire block between 10th and 11th streets, with Fayette Street to the west and the on the east. Twenty-three companies rented space in the building for storage or manufacturing. Many of these companies produced goods for the armed forces, then engaged in World War I.

As the nation was in the middle of a miners’ strike, the owners, unable to obtain coal to heat the building, shut off the sprinkler system and drained the water from the pipes to prevent freezing. A night watchman discovered a fire on the evening of January 13 and, without the sprinklers to slow its progress, it quickly engulfed the building. The fire spread to the surrounding buildings, destroying a church, a saloon, and 5 homes and damaging a grocery store and 20 additional homes before firemen brought it under control. Total damage was estimated at $2 million. Because many of the firms in the building were engaged in war production, rumors that the fire was set by German agents abounded. However, investigators were unable to find evidence to substantiate these claims.

Coliseum Explosion, October 31, 1963

The Holiday on Ice performance during Shriners Night at the Indiana State Fairgrounds performance ended in tragedy when a propane tank in the concession area ignited and exploded. A faulty valve on an improperly stored liquefied petroleum (LP) gas tank allowed gas to leak near an electric popcorn warmer.

The resulting explosion propelled the audience, seating, and slabs of concrete flooring from a 700-square-foot area around aisle 13 through the air and onto the ice. Victims landed up to 60 feet away. Some of the box seat spectators fell into the blast pit and were crushed when a damaged support wall collapsed and an additional 500 square feet of floor caved in. Within minutes the remaining propane tanks created a secondary explosion. A fireball rose from the crater to the ceiling, burning those who had rushed to the area after the first explosion and incinerating those who had fallen into the blast pit.

The police, fire department, Civil Defense, Red Cross, Salvation Army, and hundreds of volunteers, including remaining audience members used buses, ambulances, and private cars to transport the injured to area hospitals. Rescuers set up a temporary hospital in the cattle barn, and the coroner’s office set up a temporary morgue on the ice floor. The Indianapolis Fire Department used a mobile crane to lift concrete slabs still covering victims.

The Indianapolis Star established a Coliseum Disaster Relief Fund that raised over $78,000 from public donations for victim assistance. Years of litigation involving over 413 lawsuits for amounts totaling $70 million were filed for damages against various insurance companies and the State of Indiana. The LP gas firm’s insurance distributed $1.1 million among 379 victims and estates. An out-of-court settlement of $3.5 million resolved hundreds of other individual suits.

The remains one of the worst disasters in Indianapolis history.

Midstate Chemical, July 27, 1970

At 6:20 P.M. a two-alarm blaze broke out in wooden shelving in the warehouse area near the office of the Midstate Chemical company at 2100 Greenbriar Lane on the city’s northeast side. Two people were in the warehouse at the time, and fire department officials speculated that careless smoking could have been the cause of the fire. As the fire grew, it engulfed 70 cylinders of liquid chlorine located in the warehouse that weighed 150 pounds each. Investigators from Midstate, which sold liquid chlorine to the Indianapolis Department of Parks and Recreation for use in municipal pools, later concluded that only 7 of the cylinders had actually leaked during the fire. The fire nevertheless emitted clouds of noxious, yellowish-green fumes that spread over an area from 25th Street to Roosevelt Avenue and from Keystone to Martindale avenues. The fire department ordered 1,200 people to evacuate homes in the affected area.

Firefighters brought the fire under control after five hours, but both the office building and the warehouse were destroyed at an estimated loss of $150,000. Ten firemen, including Fire Chief David A. Russell, were hospitalized, and 50 others were treated at the scene for smoke inhalation. The Marion County disaster plan was ordered into effect, and ambulances, nurses, and Red Cross workers rushed to the scene and stood by to treat firemen and evacuees. Firefighters and toxicology experts from declared the area safe sometime after midnight and evacuees returned to their homes.

Grant Building, November 5, 1973

Shortly before 1 P.M., several propane tanks exploded on the fourth floor of the Grant Building at 25 East Washington Street, triggering a general alarm fire that would prove to be the most costly in the city’s history. No one was in the building as it had been vacant for some time and was being prepared for demolition. The structure collapsed after 15 minutes and the fire, aided by 20-mile-an-hour winds, spread to the 12-story Thomas Building at 15 East Washington, eventually destroying it as well. It also caused serious damage to the , Kirk Furniture, Washington Tower Apartments, and Richmond Brothers before firefighters brought it under control at around 3 P.M. In all, the fire caused over $15 million of damage.

One hundred and twenty firefighters battled the blaze and the fire department ordered over 5,000 people evacuated from buildings in the downtown area. The city’s disaster plan was ordered into effect, and 175 law enforcement officers were called in to handle crowd control and direct traffic around restricted areas. Six firefighters suffered minor injuries during the fire.

Indianapolis Athletic Club, February 5, 1992

Sometime after midnight, employees called the fire department after detecting smoke coming from vents in the lobby of the building at 350 North Meridian Street. After checking the building, the manager began evacuating the 40 guests staying in the residential rooms on the sixth, seventh, and eighth floors. The situation seemed to be under control until an explosive flashover engulfed a third-floor lounge, killing two firefighters and hospitalizing two others. A flashover—heat so intense (around 1,110 degrees Fahrenheit) that the entire surface area of a particular room catches fire at once—immediately consumed a lounge next to the third-floor dining room, overwhelming the two unsuspecting firefighters. A third victim, a businessman from Illinois, was found dead in a stairwell between the fifth and sixth floors. All three fatalities were from smoke inhalation. The fire department sent 75 firefighters and 16 vehicles to fight the fire, which caused $250,000 in damages to the nine-story building.

As a result of the three deaths, the city’s public safety director organized an Indianapolis Fire Department panel to review equipment and procedures. The panel found that firemen acted properly. Both the IFD panel and investigators from the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms concluded that faulty wiring in a refrigerator in the lounge next to the third-floor dining room caused the fire. The presence of the jurors on the sixth floor led to speculation of arson and spurred Mayor Stephen Goldsmith’s request for the ATF investigation. However, both investigations ruled out any possibility of arson.

Major Fires, 2001-2013

Since the Athletic Club fire, a number of other incidents have occurred, including the Market Square Arena fire in 2001 and the 2009 Cosmopolitan on the Canal fire in 2009. Many major fires occurred in 2013, including the Belmont fire, the Van Buren Street fire, the 30th and Clifton fire, the 9th and Sherman Warehouse fire, and the All Pro Scrap fire.

OmniSource, April 30, 2021

OmniSource Corporation, a recycling plant on South Holt Road on Indianapolis’ west side, caught fire on April 30 as the plant was processing scrap metal. The fire began at approximately 2:45 PM.

High winds hindered firefighters’ efforts to extinguish the blaze. Five departments responded including Wayne Township, Decatur Township, Indianapolis, Indianapolis International Airport, and Speedway. Six large cranes aided by moving the large pile of metal which allowed fire streams to penetrate to the center of the burning pile.

Smoke billowed 30-35 above the blaze and left a thick trail that stretched across two miles. A shelter-in-place order, lasting at least five hours, asked nearby businesses and residents to stay indoors, turn off their air conditioners and close windows. Drivers were warned of limited visibility.

The fire was extinguished at 3:30 AM Saturday, May 1 after 13 hours of effort to put out the 80,000 tons of burning scrap metal. Though no firefighters were injured in the blaze, five employees of OmniSource were monitored for injury and smoke inhalation.

Walmart Fulfillment Center, March 16, 2022

At noon a massive fire destroyed the 1.2 million square foot Walmart fulfillment Center in Plainfield, Indiana located at 9590 Allpoints Parkway. Crews from the local Plainfield Fire Department were first on the scene. They were doing a training exercise nearby when the fire broke out and were on the scene within three minutes of being notified. One firefighter suffered minor injuries while fighting the blaze. Approximately 1,000 employees, all of whom were safely evaucated without suffering injuries were inside when the fire broke out. As a precaution neighboring facilites and residents were urged to shelter in place.

It took the work of about 350 firefighters and 30 fire agencies to assist in fighting the fire. Working in 4-6 hour shifts, crews spent more than 50 hours extinguishing the blaze which was visible from miles away. At the onset of the blaze, crews spent about 30 minutes inside the warehouse fighting the fire amid thick smoke and zero visibility.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives is leading an investigation into the cause of the fire which could take weeks. Initial reports confirmed all water sprinklers in the warehouse to be fully functional. The fire appears to have started on the third floor of the warehouse. The ATF’s investigation will determine more specifics on the origin and cause of the blaze.

The Environmental Protection Agency is monitoring air quality due to concerns about the lingering effects of smoke in the air from the fire.

The warehouse contained a variety of items set for distribution including clothing, food, electronic, and shipping materials, mainly plastic and cardboard. Hazardous materials were not inside the building and five samples tested negative for asbestos.

Two months after the blaze Walmart officials announced it would not reopen the warehouse facility due to the extent of the property damage. All 2,089 employees at the Plainfield facility were offered jobs within the company.

The Sanctuary on Penn (First Lutheran Church), December 24, 2024

Shortly after 5:00 AM on Christmas Eve, a fire erupted at The Sanctuary on Penn. Despite (IFD) efforts to extinguish the blaze, the roof collapsed at 6:15 AM and the front of the building gave way shortly after 7:00 AM. Local utility provider Indiana halted power to approximately 170 customers in the area for a few hours. Fire prevention efforts kept the flames from spreading to neighboring buildings. No injuries or casualties resulted from the incident since The Sanctuary at Penn was unoccupied at the time of the fire.

The Indianapolis Department of Business and Neighborhood Services determined the building a complete loss. The risk of further collapse rendered a thorough forensic investigation impractical. Once the building was safe to demolish, the IFD commenced demolition at 11:00 AM that same day.

On January 18, 2025, former building owner J. Scott Wheeler held a “funeral” for the structure at a facility a few blocks away. Wheeler had transformed the formerly vacant building into The Sanctuary on Penn event space. The “funeral” included music and allowed guests to share memories of the National Register-listed building.

On February 24, 2025, IFD Battalion Chief Rita Reith reported the cause of the fire as “undetermined.” The compromised structural integrity did not allow investigators necessary access before the IFD demolished it within hours of the fire.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.