In the years since ratification of the 19th Amendment, no period saw more discussion of the status of women than those between 1960 and 1985. The national women’s movement that began in the 1960s was well represented in Indianapolis, where participants aggressively pursued legal, political, and social changes to improve women’s status in the face of local opposition. The consequences of this late 20th-century movement continued to have an impact on the city through 1985.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy created a President’s Commission on the Status of Women which recommended extensive legal and social changes in women’s roles. In Indianapolis and across the nation the Commission’s report spurred discussion about the status of women. In March 1968, Governor Roger Branigin (D) sponsored a “Status of Women” conference at the . The conference included sessions on the present and future roles of women in government, business, the professions, and voluntary work.

View Source

It is also true that women across Indiana were reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and discussing its meaning in their lives. (NOW) chapters grew as a result of this discussion and in Indianapolis, women active in the New Left began discussing feminism issues in the late 1960s. The promotion of feminist ideals was present at the grassroots level in addition to being considered by elected officials.

In the 1970s, women created an agenda for their movement. In Indianapolis, according to the , “the concept of equal rights [for women] was supported by Indiana lawmakers, educators, housewives, and husbands.” Although the Star overstated the case, there were clear indications of change locally as well as nationally. In 1971, the Indiana General Assembly amended the 1961 Indiana Civil Rights Law, making sex discrimination in employment illegal. The amended law passed but was strongly opposed by the only woman state senator, Indianapolis’ Joan M. Gubbins who would later lead the fight against passage of the (ERA) in Indiana. On October 12, 1971, the same day the U.S. House of Representatives passed the ERA, the Greater Indianapolis Women’s Political Caucus formed.

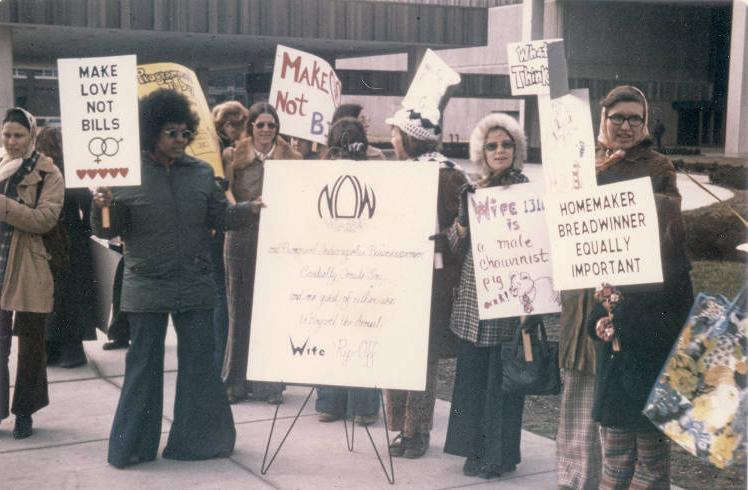

Many of its members were also members of the Indianapolis Women’s Liberation Organization which had participated in the August 26, 1970 Women’s March for Equality in downtown Indianapolis to celebrate the anniversary of the 19th Amendment and the new movement for “women’s equality.” By March of 1972, the Indianapolis Chapter of NOW was organized, and one of its early objectives was to expand opportunities for women and African Americans in radio and television (See ). Success came when members also collected statistics about women workers who endorsed women candidates and lobbied the legislature on issues such as displaced homemakers, equal pay, child support, and credit access.

Other early successes included in 1971, when Mari McCloskey obtained a court injunction against the guaranteeing her the right to enter the pits and garage area, which previously had been off limits to women.

Following a new federal mandate that no person shall be excluded based on sex from any program receiving federal assistance (Title IX), the , headquartered in Indianapolis, hired the first female member of its executive staff and the following year sanctioned girls’ sports. In 1972 the Indianapolis and the brought together women’s groups at a “Question Your Candidate” session to inform the electorate about women’s issues.

All this activity among and for women seemed to indicate a positive atmosphere locally for the ERA in the campaign year of 1972. Lobbying efforts of Indianapolis native and National Women’s Political Caucus spokesperson Jill Ruckelshaus helped persuade the national Republican Party to support ERA in its platform, making support for the ERA bipartisan. The first attempt to ratify the amendment in Indiana was unsuccessful, however, due in large part to Senator Joan Gubbins. Gubbins and conservative women championed distinct gender roles for men and women and saw feminism, especially the ERA, as a challenge to the family and women’s place as wives and mothers.

Phyllis Schlafly led the national movement for the formation of STOP ERA chapters in each state. In Indiana, chapters formed across the state, and the mobilization of both sides set the stage for an epic battle over “women’s place” in society. Conservative women like longtime Indianapolis City County Councilwoman Beulah Coughenour got their start in anti-ERA activism and Indianapolis lawyer Evelyn Pitschke gained a national audience when she became a lawyer and spokesperson for STOP ERA.

Over the next five years, women in Indianapolis (and men) mobilized on both sides of the issue. Local pro-ERA groups combined to form an umbrella organization to coordinate their efforts. Hoosiers for the Equal Rights Amendment, and attempted to rebut the argument of conservatives: Women in Communication distributed an ERA educational package, and the Greater Indianapolis ERA Coalition lobbied for passage. The , the League of Women Voters, and Concerned Women Lawyers also supported the amendment.

These groups were successful in January 1977, when Indiana became the thirty-fifth state to ratify the ERA—the first since North Dakota in 1975 and the last state ever to do so. The victory was hard fought. Although STOP ERA pushed the state legislature to rescind the amendment, Indiana’s legislature never withdrew its support of the controversial measure, however, the ERA died nationally in the 1980s, three states short of the thirty-eight needed to ratify.

The struggle over ERA consumed much of the energy of local women’s rights groups, but these groups tackled other issues of importance as well. In 1973 Mayor Richard G. Lugar’s Task Force on Women released a report on the status of women and girls in Marion County which cited lingering discrepancies in job availabilities and pay levels for women. Also in 1973 the Woman’s Anti-Crime Crusade, a volunteer group composed of thousands of Indianapolis women and the Mayor’s Task Force formed Women United Against Rape and initiated the nation’s first 24-hour rape crisis centers at nine Indianapolis hospitals. Indianapolis NOW formed its task forces in 1973 and charged them with three separate goals: to attack stereotyping of women and girls in elementary school textbooks and their absence from both history and science texts; to examine the issues of health and well-being of women with particular focus on abortion and rape; and to battle discriminatory practices against women employees and in the areas of housing and credit. NOW promoted a pro-choice state amendment following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Roe V. Wade, but the Indiana General Assembly passed a law in 1973 that allowed abortions but placed restrictions both on when and how they could be performed in the state.

The United Nations declared 1975–1985, the “Decade of Women,” and 1975 proved to be a landmark for women in Indianapolis. The Rt. Reverend John P. Craine, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Indianapolis vowed to ordain no more priests until the 1976 General Convention of the church allowed the ordination of women. Two years later an Indianapolis woman, Jacqueline Allene Means, became the denomination’s first ordained priest in the United States. In 1975 Mayor named Carlyn Johnson as the first woman to serve on the .

The appointed a new team headed by a woman to have sole responsibility for sex-related crimes. The year also marked the founding of the Julian Mission (now the ), a counseling center for women in crisis established by the woman who would become Indianapolis’ second ordained Episcopal priest, Tanya Beck Vonnegut. The Julian Center created the Sojourner Shelter for abused women in 1977. By the end of the 1970s Indianapolis attorney became the first woman federal prosecutor in the nation in 1977, and Janet Guthrie made national headlines as the first woman to attempt to qualify for the .

Conservative women, who opposed the call for “equality” in favor of respect for gender difference, had opposed the ERA and continued their opposition to feminist initiatives. Local and statewide right-to-life groups, STOP ERA, and Indiana Pro-America gathered a contingent that outnumbered feminists four to one at the statewide International Women’s Year convention in Indianapolis in 1977. Thirty-two Indianapolis women joined the thousands who attended the National Women’s Conference in Houston later that year. Although the conference would present a feminist women’s rights agenda to the nation, Indiana’s delegation was overwhelmingly pro-family, pro-life, and anti-ERA.

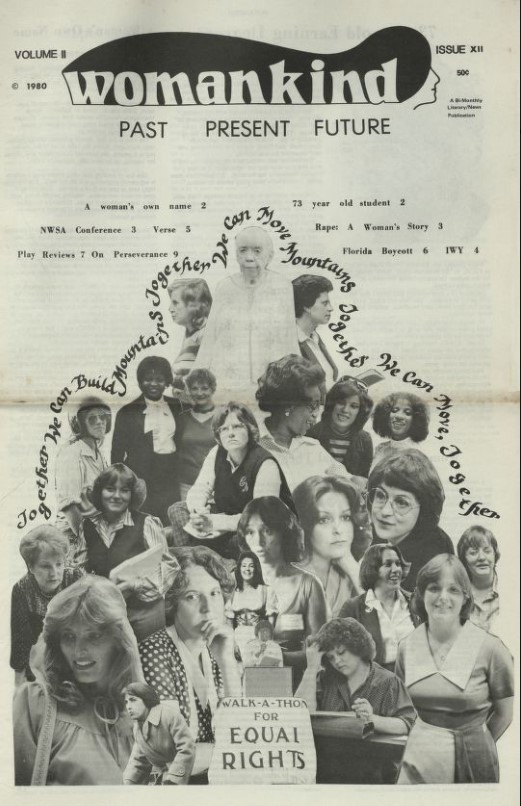

The 1980s brought new issues to the forefront of the women’s movement and saw increasing numbers of women entering traditionally male professions as barriers fell. In 1981 Judith LaFourest opened the Womankind Center at 3711 N. Sherman Drive in Indianapolis. The venue offered “womanspace for women’s needs,” including time-shared office space. LaFourest published , a nationally known feminist newspaper at the center, and a feminist bookstore, Dreams and Swords, was located there. In 1983 the Indianapolis League of Women Voters published a 56-page booklet, “Financial Awareness for Women in Indiana,” which was a guide to state laws that concerned women. The following year an 18-month study of metropolitan Indianapolis girls and women conducted by found the majority of respondents were torn between the traditional roles of wife and mother and the modern roles of careerwomen. Despite disagreement between conservative and feminist women, Indianapolis saw one of the few collaborations between the two sides.

In 1984 feminists, led by national feminist leaders Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, and conservatives led by Beulah Coughenour, successfully lobbied the Indianapolis City Council for an ordinance that classified pornography as a form of sexual discrimination. This ordinance was deemed unconstitutional by a federal district court. In 1985 , and that ruling was upheld through the appeal process but represents one of the few points of agreement across the political divide.

In 1985, New York-based Savvy magazine declared Indianapolis one of the six worst cities in the nation for working women. Although some women agreed with the assessment, others cited changes that showed women’s status was improving but allowed that women often had to work harder to achieve promotions. That year the city saw its first woman promoted to captain in the Indianapolis Police Department (IPD), with the first woman IPD major the following year. Also in 1985 “From a Woman’s Point of View,” a local conference focusing on women’s health, sexuality, family relations, and aging won a CASPER award for “outstanding communication achievements.” In 1986 Jill Andresky Fraser’s listed Indianapolis among the 70 top cities in the U.S., calling it a “turnaround” city with “as yet unfulfilled” potential for women to advance. Still, a survey of Indianapolis women attorneys in 1989 found a preponderance of males in management positions.

The women’s movement that began in the 1960s and continued in the 1980s addressed issues of importance to women, while also revealing divisions among women and the larger society regarding the meaning of equality. Despite strong opposition at times, the movement in Indianapolis claimed much success in raising the status of women in the workplace and society.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.