In 1907 Indiana Governor Frank Hanly signed the Indiana Sterilization Law, which is widely considered the first eugenics sterilization legislation passed in the world. The new law passed by the state legislature and signed by the Governor of Indiana provided for the involuntary sterilization of confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles, and rapists. It was eventually found to be unconstitutional. Even before the 1907 law, a 1905 Indiana law forbade the mentally deficient, those with a transmissible disease, probably a reference to syphilis, or habitual drunkards from marrying.

In 1927, a revised eugenics law was implemented and before it was repealed in 1974, it resulted in the sterilization of over 2,300 of Indiana’s most vulnerable citizens. In addition, Indiana established a state-funded committee on Mental Defectives that carried out eugenic family studies over 20 counties and was home to an active “better babies” movement that encouraged scientific motherhood and infant hygiene as routes to human improvement.

The social change that was sweeping Indiana in the early 1900s drove the popularity of eugenics. What was once an overwhelmingly agricultural and rural state gradually converted to a more urbanized, educated, scientific, and modern society. Rural and impoverished segments of society became more aware of their marginalization. The class differences between middle-class investigators and those they investigated played a role in the classification of many of the urban and rural poor as degenerate.

The eugenics movement has an important connection to Indianapolis. A prominent local minister and reformer, Reverend , conducted extended family studies in the late 1870s and early 1880s on a group of poor white urbanites he dubbed the . McCulloch tried to prove that certain family groups were posing undue burdens on the state through irresponsible living and high birth rates (as such people were more likely to spend time in jail and be on public relief).

Eugenic researchers saw the Ishmaelites as prime examples of their movement. Naming the group of people Ishmaelites intentionally sharpened focus on the threat this group posed to society. Though the group in the “tribe” were white citizens, the Arabic-sounding name emphasized the degenerative traits the group carried and could propagate if not stopped through compulsory sterilization.

McCulloch noted the diversity within the Ishmaelites, people originating from freed or escaped African enslaved persons, Native American tribes, and Europeans who had escaped indentured servitude and whose norms clashed with those of mainstream society. He defined them as a parasitic group composed of drunkards, prostitutes, and drug addicts.

McCulloch implied that urban whites could devolve into Gypsies, Muslims, or other undesirable races who represented the undeserving poor draining society of its resources. His influence grew when he started the State Board of Charities (SBC) in 1889. The Board or its committees visited the principal state institutions under their supervision conducting investigations and reporting their findings to the Indiana General Assembly. McCulloch’s studies about the Tribe of Ishmael took on national significance when they were used as primary evidence to convince the U.S. Congress to implement the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924.

Indiana’s first sterilizations occurred prior to the passing of the sterilization law. These surgeries were carried out by Dr. Harry Sharp on over 100 male criminals in the Indiana State Reformatory at Jeffersonville, Indiana, in an effort to cure masturbators. Starting in 1899 Dr. Sharp sterilized about 450 males at various state institutions in Indiana. The safety and inexpensiveness of the surgery gave further ammunition to eugenics advocates who had been working for at least two decades to develop ideas about criminality, degeneracy, hyper-sexuality, and the primacy of heredity in determining personality and familial traits.

Sharp lobbied the Indiana government to use sterilization to cure problems of mental deficiency and sexual deviance in Indiana. When Indiana Governor Frank Hanly signed the Indiana Sterilization Law on April 12, 1907, it allowed the superintendents of Indiana State prison, asylum, and reformatories to appoint two surgeons to investigate candidates for sterilization in those institutions. If the surgeons thought society would benefit from them not having children, the person would be sterilized. Indiana’s eugenic sterilization measures were perceived as ways to stop the dregs of society from reproducing themselves.

In 1909 a new governor, Thomas Marshall issued a moratorium on sterilizations after complaints of involuntary sterilizations came from the Jeffersonville institution. Marshall further threatened to stop funding institutions that continued to use the law. The Indiana Supreme Court formally struck down the law in 1921 citing violations to the Fourteenth Amendment.

Indiana used its state and county fairs to maintain eugenics ideas even after the first law was struck down for lack of due process. State and county fairs hosted “better baby” contests and fitter families for future fireside events, which helped maintain public interest in the ideas of human heredity and were essentially slogans to hide eugenics. Indiana hosted these events at the .

In 1920, Indiana’s Division of Infant and Child Hygiene inaugurated its first Better Baby Contest at the state fair. For the next 12 years, these contests were the centerpiece of a dynamic infant and maternal welfare program that took shape in Indiana during the decade of the federal Sheppard–Towner act. More than just a lively spectacle for fairgoers, these contests brought public health and race betterment together in a unique manner.

In 1915 Indiana Governor Samuel Ralston took over the SBC and created the Committee of Mental Defectives (CMD). It worked during a period when virtually no sterilizations were performed. From 1915 to 1924, a body of female social workers combed through homes and schools measuring IQs and traits such as alcoholism, promiscuity, and insanity in their quest to keep interest in hereditary defectiveness alive. The CMD team determined that 2 percent (56, 000 people) of Indiana residents were mentally defective.

These findings helped spur momentum for sterilization to return to Indiana. Based on CMD study evidence, a new sterilization bill was introduced in the Indiana General Assembly in 1925. This legislation, however, failed to pass.

Yet within a few years, the U.S. entered the period of legalized sterilization. The landmark U.S. Supreme Court Case Buck v. Bell, decided on May 2, 1927, upheld states’ rights to sterilize those deemed mentally defective. Thus, in Indiana, a new law passed in 1927 that allowed for the sterilization of the insane, feeble-minded, or epileptic. The law cleared any potential interpretation of violating the Fourteenth Amendment and was designed to target individuals housed within state institutions, not those in the general population.

Though an institution’s superintendent and governing board could determine if a candidate should be sterilized, a candidate’s family had the option to appeal the verdict. The law was expanded in 1931 to empower county judges, with the approval of two physicians, to order the sterilization of the feebleminded and insane during their commitment procedure.

One factor that led to the increased rates of sterilization seen in the 1930s was the Great Depression. Indiana institutionalized innumerable men and women unfit to live independently. They were placed in the two homes for the feeble-minded in Fort Wayne and Muskatatuck, the Indiana Village for Epileptics in New Castle, and in Indianapolis,

The economics of the Depression Era squeezed state funding for these facilities. Budgetary constraints pushed institutions to seek ways to release patients and inmates. Sterilization provided an answer. Patients could be released without posing a threat to society since they would not be able to reproduce and propagate their unwanted traits to another generation. To reduce the number of patients, Indiana state officials granted exit papers to those patients desiring to leave contingent on undergoing sterilization.

In Indiana, under the public health pretext of eugenics 2500 Hoosiers were sterilized before Governor Otis Bowen ended the practice in 1974. The state did not issue a formal apology to those who suffered sterilization procedures until 2006.

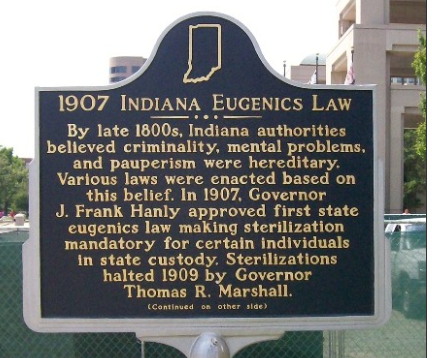

In 2007 historical marker 49.2007.1 was erected to commemorate those sterilized under the Indiana Sterilization Act. The marker was erected by the , Indiana University, and Indiana University Foundation. It can be found at 140 North Senate Avenue on the East lawn of the Indiana State Library.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.