Indianapolis’ contemporary drag scene traces its roots to the 1960s. However, drag queens, who were originally called female impersonators, could be found as far back as the 1860s in traveling minstrel shows performing at Masonic Hall. The first real documented evidence of what could be considered a drag show performance in Indianapolis occurred on on August 5, 1933. Thousands of patrons came to watch openly queer Black entertainers perform at the Paradise Gardens, located at 427 Indiana Avenue.

Paradise Gardens was not the only venue for Black drag performances along the Avenue. Other venues included the Cotton Club, the Log Cabin Supper Club, and even the . The Famous Door, located at 252 North Capitol Avenue, provided a racially integrated space for both performers and audience. It was known to host some of the best drag shows in Indianapolis.

Early Black drag performances were often part of , cabaret, or other forms of comedic performance. The use of cross-dressing and comedy as a form of self-expression may have provided a safe and less overt outlet for early queer individuals to experiment with sexual expression. Still, visibility of queer culture along the Avenue was met with pushback. In 1933 the police chief was praised for his raids that shut down drag shows. This led to club owners’ hesitation to advertise drag performances in order to quell raids and protect drag performers. Even so, these predominantly Black female impersonators and performers continued on or near the Avenue.

A combination of factors caused displacement of the Black drag scene along the Avenue in the 1970s-1980s. Redevelopment of the city’s near-northwest side as well as the addition of a parking garage at the , and the continual expansion of the campus at all contributed to mass demolitions of structures on and near Indiana Avenue. These forces weakened the Avenue’s power as a commercial corridor and center of Black culture and caused displacement of Black drag venues, performers, and patrons. Additionally, the HIV/AIDS crisis, along with related discrimination and harassment of the LGBTQ community, particularly by law enforcement, drove drag show performances and the first wave of explicitly LGBTQ bars underground to remain anonymous and safe.

The white drag scene happened out of sight, in venues catering to cisgender white gay men. These venues, with opaque doors and windows to shield white drag performers, included Our Place (aka O.P.’s and Greg’s), the 21 Club (aka Johnnie’s Place and Harlow’s), Tomorrow’s (aka Gravel Girties, Meridian Pub, Sherry’s, and Tropica Bay), Talbott Street (aka the former Talbott Theatre and Henzy’s), Downtown Ollys (aka The Uptown Connection and Brothers), the 501 (aka Club 501 and 501 Eagle), Zonie’s Closet (aka Illusions and Macebob’s) and many more. The white drag scene, now above ground, did not fully come of age until the 1980s.

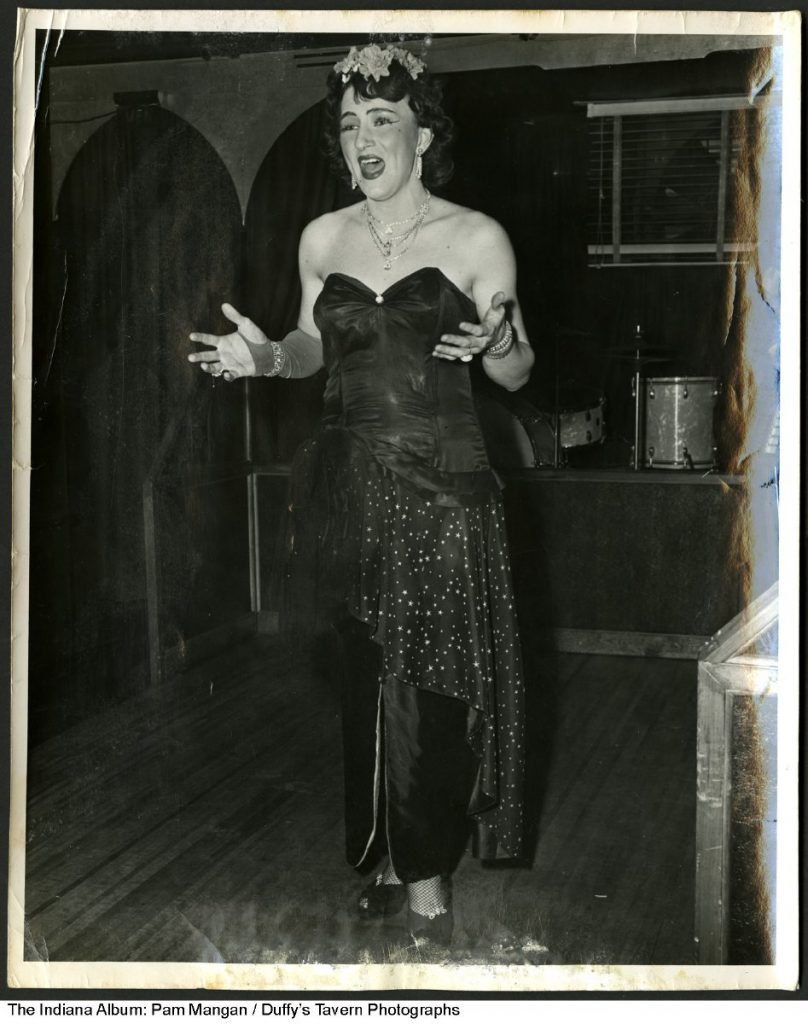

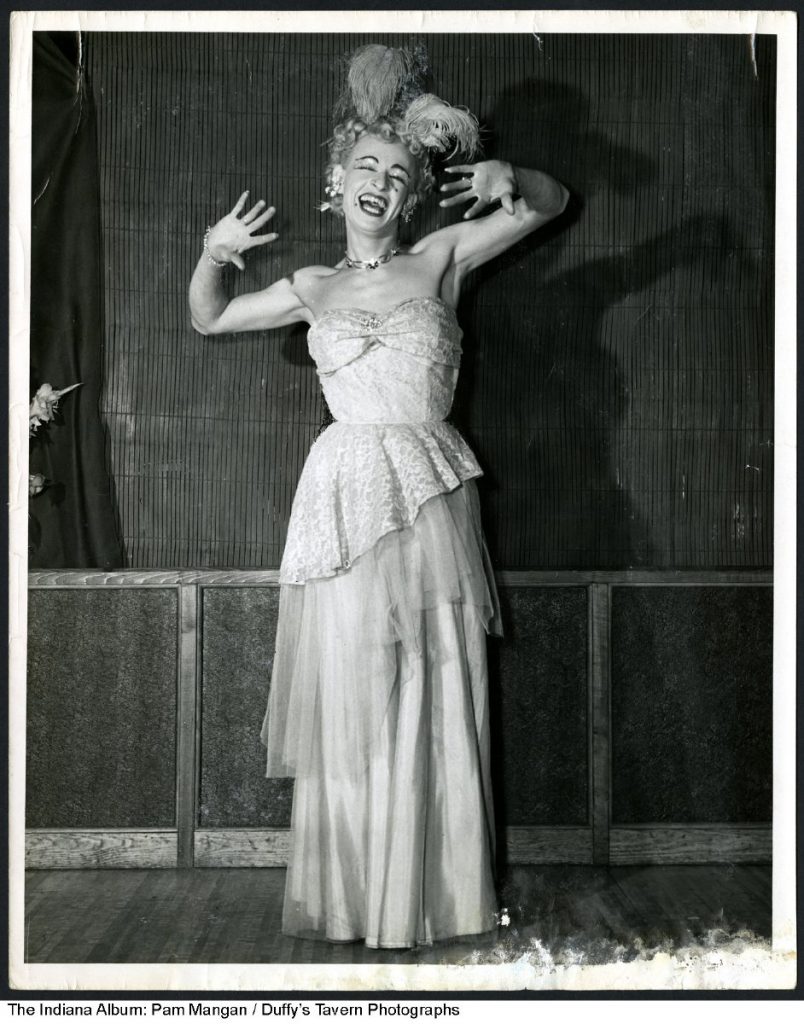

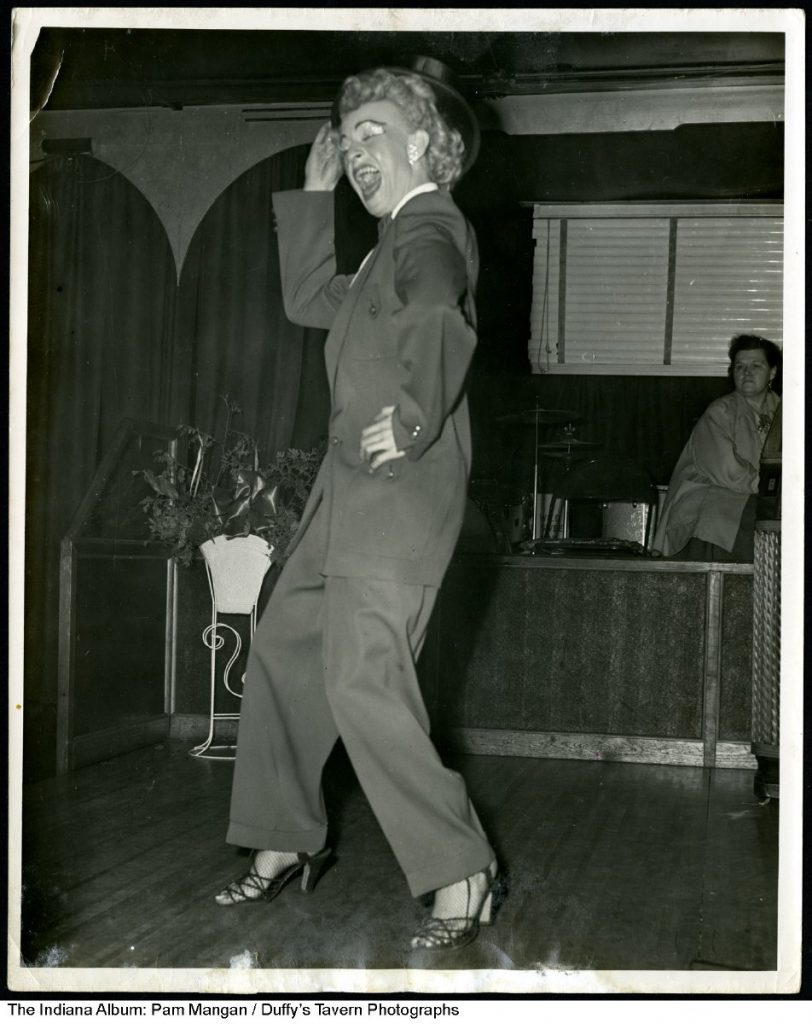

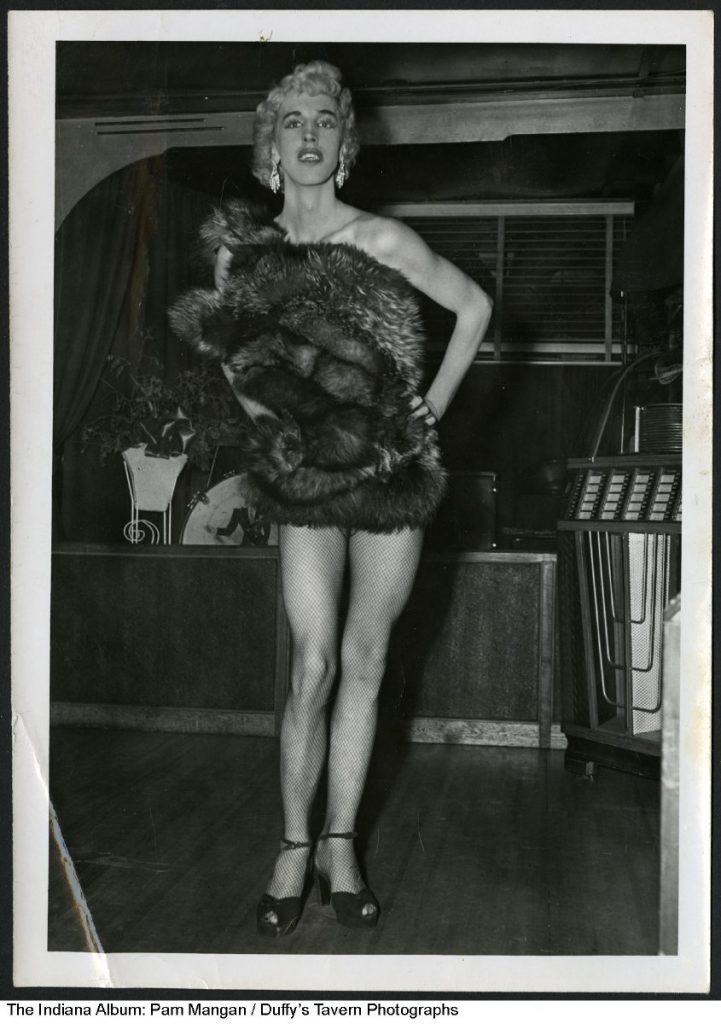

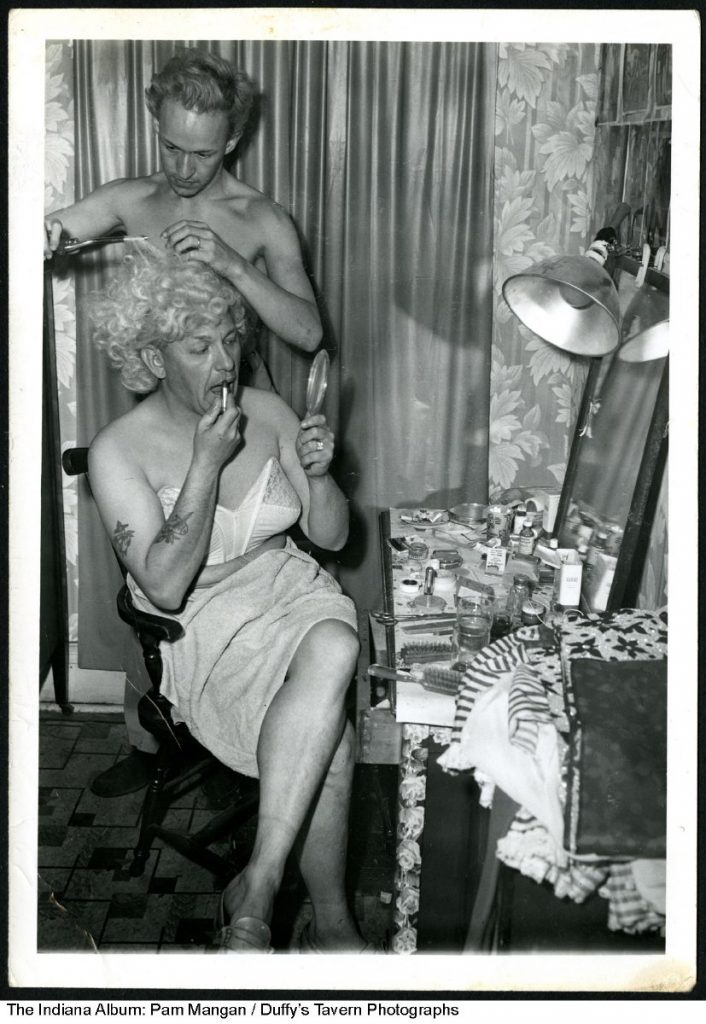

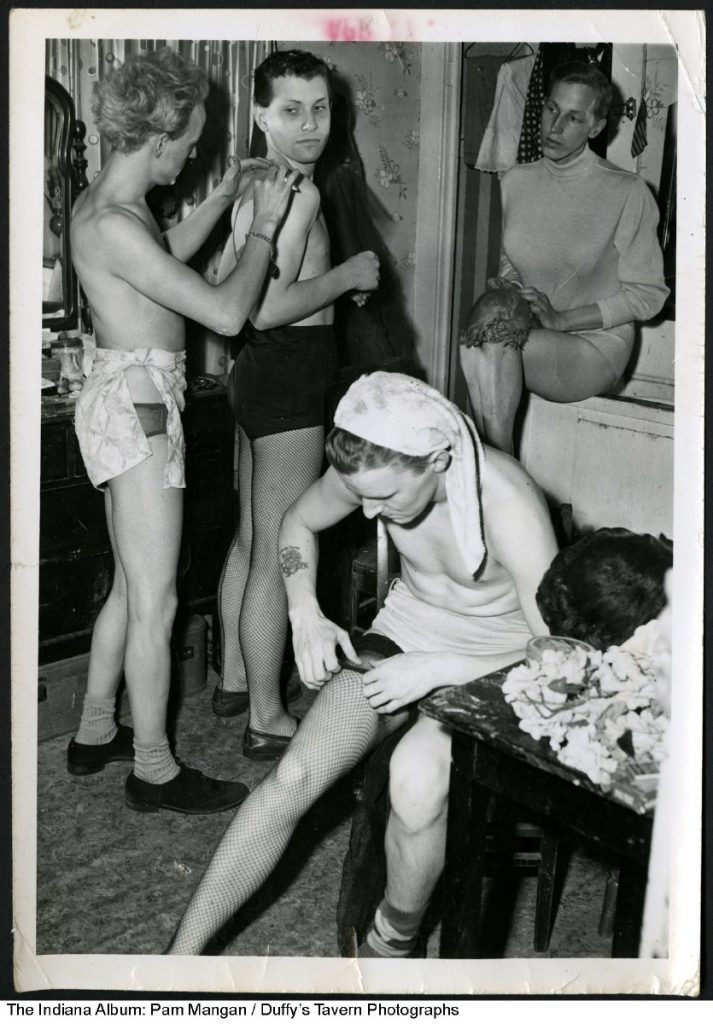

However, Duffy’s Tavern provides an example of local drag performance from the early 1950s. Robert and Ruth McDuff operated the bar, located at 2001 Shelby Street on the city’s south side, between and , from 1949 to 1953. From its beginnings, the tavern showcased “exotic dancers,” and in April 1953 it began featuring “female impersonators,” later known as drag queens. Duffy’s Tavern closed after the McDuffs lost their liquor license in August 1953.

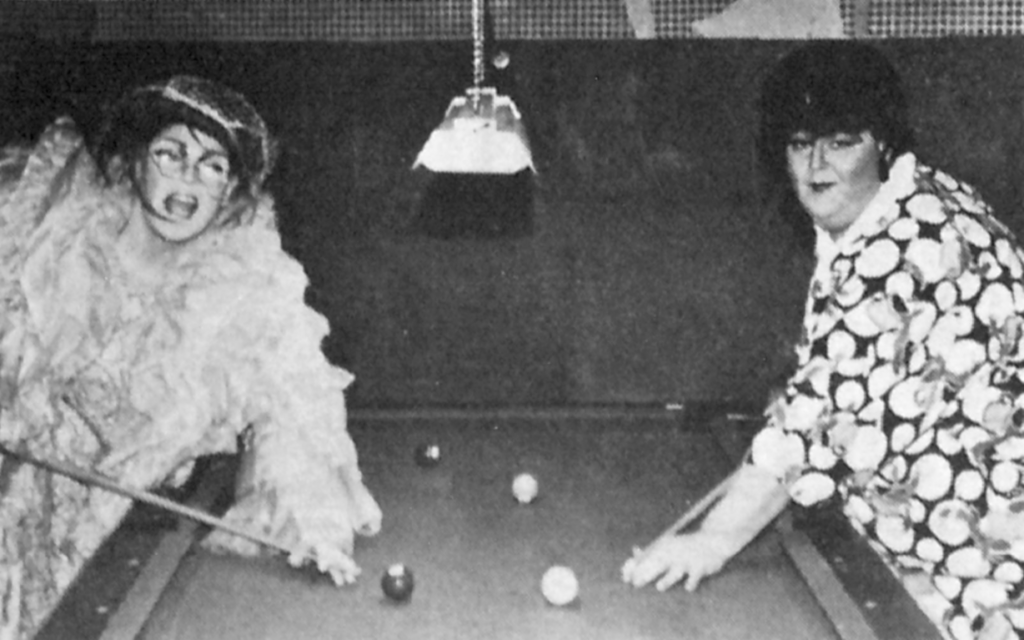

Queer bars in the 1980s-1990s, and even into the 2000s, were not always equally inviting to members of the LGBTQ community, particularly on the axis between cisgender gay men and cisgender lesbian women, but also on spectrums of race and gender identity. Gender-line divisions created the need for establishments that provided similar forms of entertainment for women clientele. Some of these venues included The Ten (aka Ruins), Labryis, Club Betty K (aka Betty K’s), Darlo’s, and Shirley’s Place (aka One-Way, Tubes, Club 151, and Club Cabaret). Though Black drag queens popularized drag entertainment along the Avenue, Black-centric drag was erased or incorporated into mainstream drag shows. Transgender individuals struggled with internalized discrimination within the community. Documented discrimination against transgender individuals occurred at The Varsity Lounge, Our Place, and the 501 Tavern, though there were likely many more instances at other bars and venues.

New challenges arose by the 2010s. Indiana’s 2014 House Joint Resolution-3, a proposed constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage in the state, and the 2015 , a law granting religious liberty rights to individuals at their discretion, threatened civil liberties and protections for the LGBTQ community. Also, during this time, many queer bars shuttered their doors, including The Varsity Lounge, Talbott Street, The 501, and The Ten. These closures have been attributed to smartphone dating apps that changed the nature in which people meet, an increase in LGBTQ acceptance which decreased the need for identity-specific bars, and the choice of bar operators, managers, and owners to take advantage of a robust real estate market.

In 2017, Low Pone was established in reaction to the wave of closures and the obvious need for a more inclusive drag show performance. This monthly event was first held at the Hi-Fi, then at Pioneer, and later at the White Rabbit Cabaret. The success of Low Pone led to the creation of Low Pone’s sister events including Sweet Hussy, a queer rock ‘n’ roll dance party at The Melody Inn; Minor Sweat, an all-ages experimental drag performance night for younger people at ; and Buzz/Cut, the state’s first LGBTQ music festival in .

Throughout the history of drag in Indianapolis, some attempts have been made to introduce drag culture to straight audiences. Early drag brunches started in the 1950s through the 1970s as a way to avoid nighttime raids of establishments hosting drag performances. By the 2000s drag brunches could be found at establishments such as Baby’s, The Hulman, the Skyline Club, and Feinstein’s at Hotel Carmichael in Carmel.

Another way that drag culture has been brought to a wider audience is through Drag Story Hour, a program that was first created in 2015 in San Francisco, which focuses on teaching literacy and acceptance of diversity to children. Drag Story Hours have been held in Indianapolis by organizations such as the and . These events have often faced threats, protests, and violence from hate groups.

FURTHER READING

- Lane, Stephen M. “The Female Impersonators of Indiana Avenue: Race, Sexuality, Gender Expression and the Black Entertainment Industry.” Indiana University, 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/1805/27151.

- Poletika, Nicole. “‘Walk a Mile in Their Pumps:’ Combating Discrimination within Indy’s Queer Community.” Untold Indiana, October 7, 2020. https://blog.history.in.gov/walk-a-mile-in-their-pumps-combating-discrimination-within-indys-queer-community/.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Ryan, J. (2025). Drag Performances and Venues. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 21, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/drag-performances-and-venues/.

MLA:

Ryan, Jordan. “Drag Performances and Venues.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025, https://indyencyclopedia.org/drag-performances-and-venues/. Accessed 21 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Ryan, Jordan. “Drag Performances and Venues.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2025. Accessed Feb 21, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/drag-performances-and-venues/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.