Dispensaries were precursors to hospital outpatient clinics and health clinics for the poor. During the Civil War civic leaders petitioned the Indianapolis City Council to establish a dispensary for those unable to pay for medical treatment and to provide a source of continuing education for medical students and practitioners. The first private dispensary was Bobbs’ Free Dispensary, established around 1870 with a bequest from Dr. and associated with the Indiana Medical College.

Soon thereafter , a prominent physician and son of , established a city dispensary. Serving as its superintendent (1875-1879), Fletcher oversaw care for the poor and the city jail’s prisoners, treated smallpox cases, and administered vaccinations. In 1875 alone, dispensary physicians made 5,563 home visits, treated 4,210 patients at the dispensary, and filled 10,232 prescriptions.

The city dispensary’s early years were filled with controversy (including a battle for control of the institution) and financial problems. Despite battles over whether the Indiana Medical College or private physicians would be more efficient in operating the dispensary, the city’s Committee on Hospitals refused to cede control. Funds for the institution—half from city appropriations, half from private contributions—also proved inadequate and limited the purchase of medical supplies.

In 1879, the City Council reorganized the dispensary as a government-funded agency with a full medical staff and imposed tighter controls to prevent abuse of medical services. The reform did not eliminate the dispensary’s financial woes, win additional funds, or protect it from local politics. The council created another health board in 1891, placing the dispensary and City Hospital (see ) under its jurisdiction but with no increase in appropriations.

The need for the dispensary became most apparent during the 1893 depression. Cases treated rose from 7,313 in 1892 to 20,938 in 1893. After schools began requiring the immunization of children, unemployed parents incapable of paying medical fees turned to the dispensary where one physician remarked that “the sidewalk… is crowded all the time with those who are waiting for the opportunity to be vaccinated free.”

When Superintendent Edward D. Moffett requested $30,000 for a new dispensary, he encountered a public that accused the city of being extravagant in its funding for the poor. Mayor recommended a $10,000 appropriation instead, noting, “We do not believe in making charities of any kind popular and thus destroying the sense of individual responsibility.”

Over the next several years, the dispensary continued to be a political battleground. Claiming no need for a new dispensary. Superintendent John F. Geis (May-August 1894) criticized previous superintendents for prescribing expensive treatments for trivial ailments. Subsequent superintendents John Lambert (1894-1895) and Leonard Bell (1895-1897), however, described the facility as “unsafe, uncomfortable and unsightly” and a “counterpart of the poverty-stricken conditions of the patients.” The Indianapolis Sanitary Association reported that “it is a disgrace to the City.” While the dispensary received complaints about inadequate staffing and poor funding, conservative opponents claimed the majority of cases treated at the dispensary were those arising from “disgraceful causes, for which the public is not responsible and should not be called upon to treat.”

In 1897 the city constructed a new dispensary on South Alabama Street, but it suffered the same problems of earlier years. While physicians were treating 20,000 patients annually by the early 1900s, some improvements were forthcoming. The City Hospital Training School for Nurses provided nurses for the dispensary’s “house call” program. The dispensary also established a tuberculosis clinic in 1908.

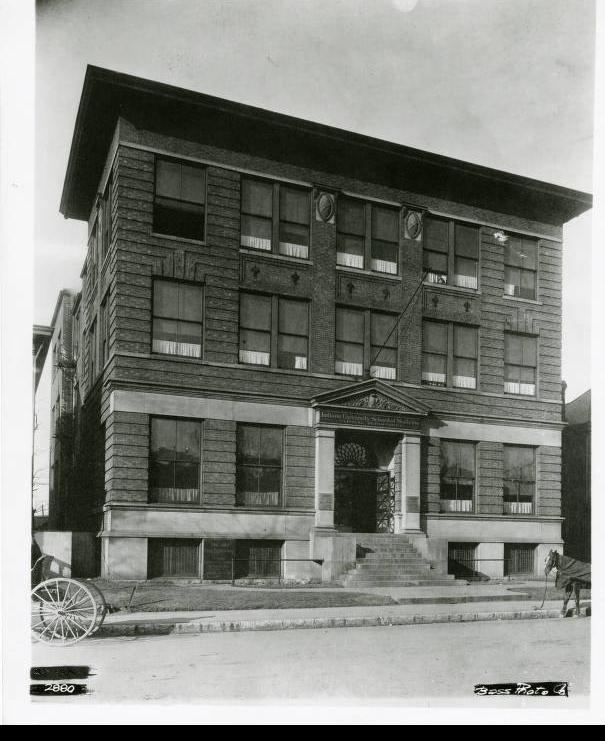

To give “proper attention to all cases of illness among the city’s poor,” the city dispensary merged with Bobbs’ Free Dispensary (by now a part of the ) in 1909 and moved to new headquarters located at Senate and Market streets. Within a few years, it had established clinics for tuberculosis patients, syphilitics, pediatrics, and obstetrics, among others. The dispensary was open 24 hours a day and provided ambulance service for the poor. Reaction to the reorganized dispensary was generally positive as the reported in 1911 that the dispensary “is now upon a higher plane than ever before.” Also in 1911, Indiana University established its Social Service Department (today the Indiana University School of Social Work) at the dispensary, with as the department’s first director.

Conflicts between the city and the university regarding the role of the dispensary continued. The medical school viewed the dispensary as a training facility for interns and a laboratory to gather statistics about social conditions and physical maladies. The city, however, considered the dispensary solely as a source of inexpensive health care for the poor. On October 31, 1915, the health board broke its contract with the university, assumed total control of the dispensary, and canceled the school’s privileges at City Hospital.

Supporters of the medical school-operated dispensary argued that the university’s association with local clinics had earned the school its “top five” status from the Carnegie Foundation in 1915. City and medical school officials eventually resolved their differences and resumed dual control of the facility. The dispensary remained a vital force in the care of Indianapolis’ sick poor, providing smallpox vaccinations and public health nursing. The dispensary ended as a freestanding unit in 1929 when City Hospital merged its outpatient services, social service department, and dispensary into its new A-wing.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.