The Indianapolis military-commission “treason trials” of 1864 arose from the threat posed to the Union war effort and the survival of the United States by secret organizations that existed in Indiana and neighboring states. From the outset of the Civil War, government and military officials throughout the Old Northwest saw evidence of the existence of secret organizations tied to the that aimed to rally opposition to the Union effort to coerce the rebel states back into the national Union.

Civil and military leaders perceived secret actions to subvert the war effort. In 1861 and 1862, civil law-enforcement officers investigated but were unable to counter the secret groups, which at that time went by the name the Knights of the Golden Circle. In 1862, military commanders began to investigate the secret organizations, whose members discouraged volunteering, impeded recruiting, encouraged desertion, and harbored fugitive deserters.

In 1863, military commanders in Indiana and other states established detective operations to collect information on, among other things, the actions of the secret groups. During that year officers succeeded in breaking up efforts to impede the draft enrollments and attack prisoner-of-war camps in Ohio, Indiana, and elsewhere. However, civil trials in federal courts were ineffective in bringing conspirators to justice.

By 1864, it became clear to both military commanders and Republican governors in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois that the secret organizations were large and collaborating with Confederate agents and troops. They posed a serious threat to the Union. Military intelligence efforts succeeded in infiltrating the organization, by then called the Order of American Knights and, after February 1864, the Sons of Liberty. Commanders learned who the organization’s leaders were.

U.S. Army spies gathered information that afforded officers the ability to take the offensive against the conspirators. In July 1864, the army commander in Kentucky pressed governors and generals north of the Ohio River to arrest leading conspirators and, bypassing the slow federal and state civil courts, try them by military commissions. While the governors of Ohio and Illinois feared such arrests would spark uprisings by the rank-and-file of the organization, Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton and the top general in the Old Northwest, Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman, approved of the plan and pressed leaders in Washington, D.C., to accept it.

President Lincoln had previously dismissed the threat from the conspirators. In August 1864 he concluded, however, that the Union war effort was going badly and feared he would be defeated in the fall election by his Democratic opponent. Lincoln changed his mind, took the threat from the plotters seriously, and gave the generals reinforcements and authority to act against them. In early September, his War Department sent instructions to Brevet Maj. Gen. Alvin P. Hovey, commander of the military District of Indiana, to try conspirators by military commission.

In early September 1864, Hovey arrested the state “grand commander” of the Sons of Liberty in Indiana, Indianapolis businessman and prominent Democrat . He quickly assembled a commission made up primarily of high-ranking Indiana officers and charged Dodd with disloyalty and conspiracy.

Meeting initially in the courtroom in the federal courts and post office building (the tribunal convened later in the chamber of the Indiana Supreme Court in the ), the military commission trial began on September 27. It was open to the public and the newspapers, which gave the proceedings prominence, typically printing verbatim accounts.

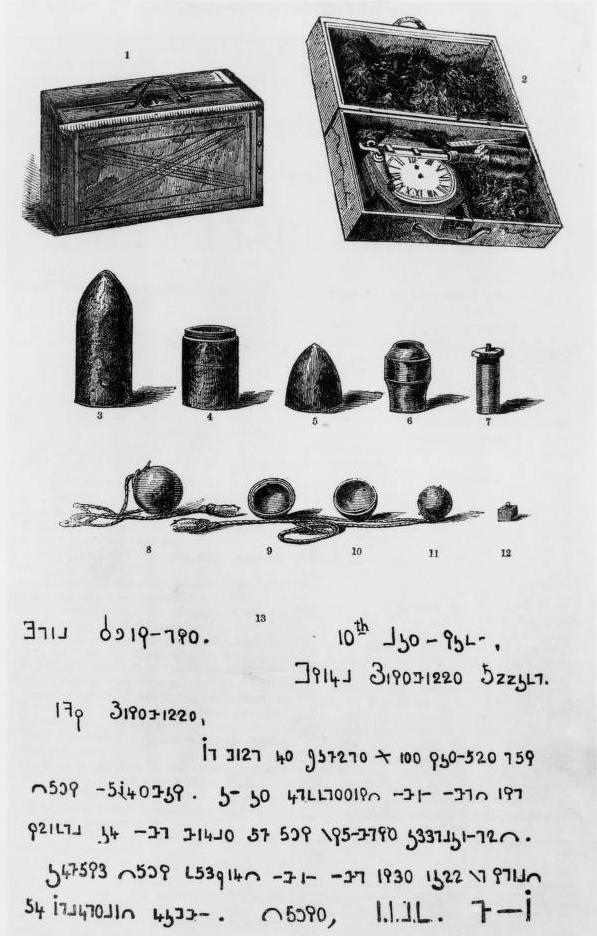

The star prosecution witness was army spy Felix G. Stidger, who had served as the secretary of the Kentucky branch of the Sons of Liberty and, in that role, had met frequently with Dodd and other Indiana conspirators. Stidger told of plans to foment armed uprisings, free Confederate prisoners, assassinate soldiers, and collaborate with Confederate guerrillas. The trial, extensively publicized, created a sensation.

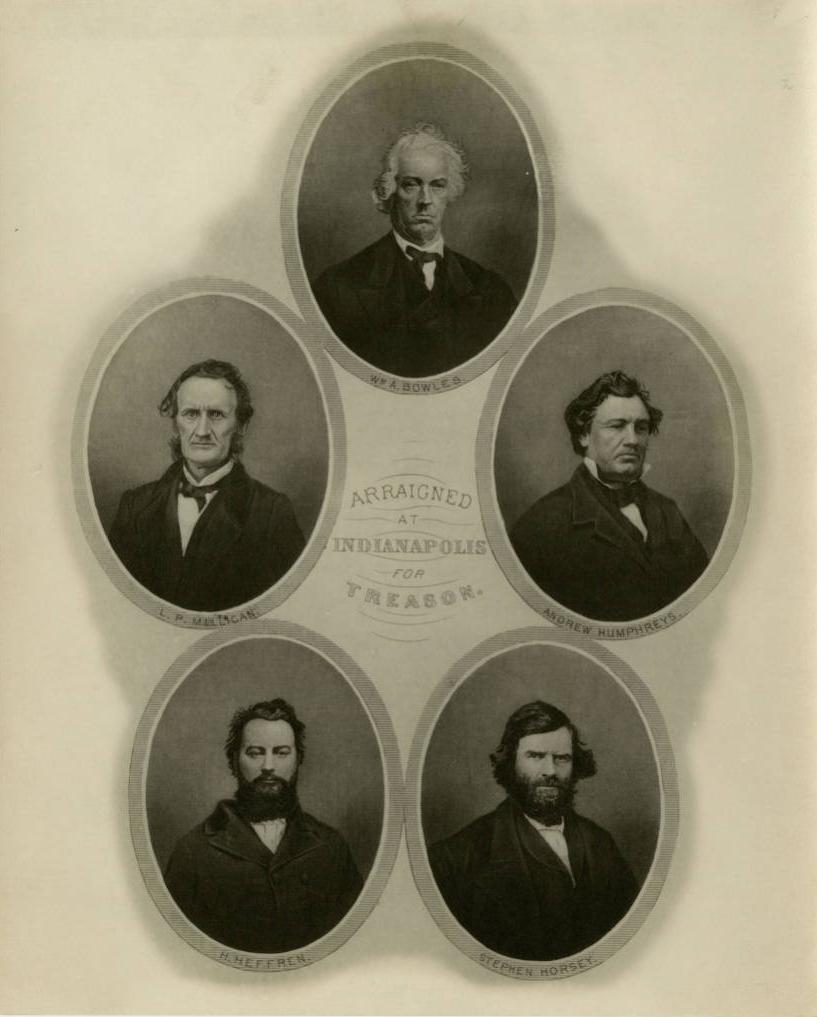

In early October, Hovey issued orders to arrest other leaders of the Sons of Liberty, sending troops around the state to seize (state Democratic Party chair and publisher of the , the state Democratic Party organ), William A. Bowles, Horace Heffren, Stephen Horsey, Andrew Humphreys, and Lambdin P. Milligan. They also were charged with disloyalty and conspiracy.

In the early morning of October 7, Dodd escaped from his prison cell in the federal building and, despite careful efforts to catch him, fled to Canada. After a short pause, his trial continued with Dodd in absentia. The commission members found him guilty and sentenced him to death, though the verdict was sealed.

The trial of the new defendants commenced, with the army judge advocate, or prosecutor, Maj. Henry L. Burnett, calling as witnesses a string of detectives and informants. He dropped charges against defendants Heffren and Bingham, who became prosecution witnesses, recounting details of plots and plans. They conveniently diverted much blame on the absconded Dodd, thus shielding themselves and others from complicity.

The trial continued into December. By that time, the October state and November presidential elections had occurred, giving Republicans major victories and ensuring that the war effort to defeat the Confederate rebellion would continue. Defense attorneys called witnesses to impeach the character of the prosecution witnesses, especially those who had been spies or informants for the army.

In defense summations, lawyers argued that the spies had acted as agents provocateurs. The officers of the commission ignored defense arguments and found all the defendants guilty. They were sentenced to death (except Humphreys, who was placed under house arrest in two townships of Greene County, Indiana). The verdicts were kept secret until President Lincoln could review and approve them. He confirmed their sentences in January 1865.

Attorneys and friends of the condemned defendants made efforts to appeal the verdicts. After Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson commuted Bowles, Milligan, and Horsey’s death sentences to life at hard labor. Meanwhile, Milligan’s attorneys obtained a split decision in a habeas corpus writ from the two judges sitting at the U.S. Circuit Court in Indianapolis, sending the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The court heard arguments in the case in Washington in March 1866, and in the following month, it ordered the three prisoners released from prison in Ohio. In December 1866, the ruling, Ex parte Milligan, appeared. In it, Justice David Davis (who had sat as a member of the Circuit Court in Indianapolis and forced the split decision) wrote that civilians cannot be tried by military tribunals when and where the civil courts are open for business. Constitutional scholars and jurists have hailed the Ex parte Milligan ruling as a major civil liberties statement.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.