As the political capital and railroad hub of Indiana during the American Civil War (1861-1865), Indianapolis became an important military center, especially for operations in the western theater. Officials in the War Department in Washington, D.C., designated the state’s capital as a rendezvous place for volunteer troops, and federal and state leaders placed several military camps and other installations in and around the city.

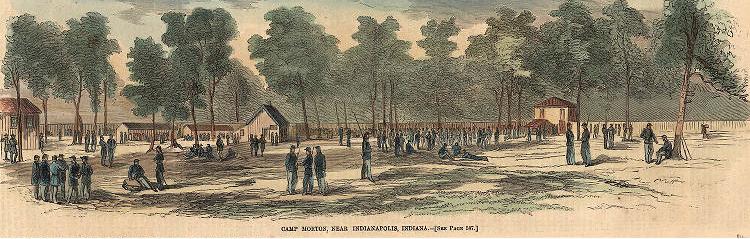

In April 1861, shortly after Confederate rebels fired on Fort Sumter, volunteers flocked to Indianapolis to suppress the rebellion. Troops first gathered on the ground previously set aside by the state government as a state-militia training ground, later called . At the time, it was called Camp Sullivan after Col. Jeremiah Sullivan, commander of the 13th Indiana Volunteer Infantry regiment. Shortly afterward, more troops organized and drilled on the new to the north of the city (later around 19th and Delaware Streets), which the troops named Camp Morton after Gov. Oliver P. Morton.

The camp served as a rendezvous for volunteer units until February 1862, when federal military officers requested Gov. Morton to accommodate thousands of rebel prisoners of war captured at the Battle of Fort Donelson in Tennessee. For most of the remainder of the war, Camp Morton functioned as a prison camp confining thousands of Confederate soldiers.

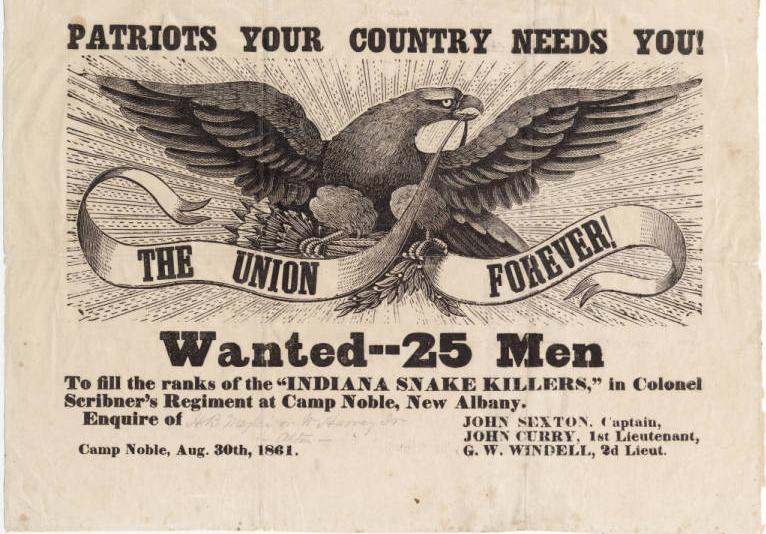

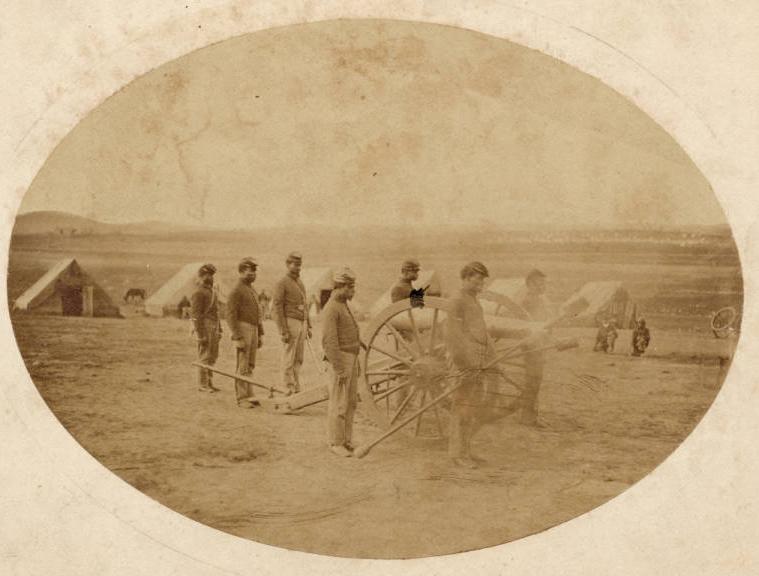

To accommodate the necessary prison-camp garrison, commanders constructed additional military facilities adjacent to Camp Morton. Burnside Barracks, named after Indiana native Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, was located just south of the prison camp. Officers also housed troops in other locations in and around the city. Camp Carrington, named by soldiers after Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Henry B. Carrington, was located north and west of Indianapolis. Camp Noble, named after the adjutant general of Indiana, Laz Noble, and located north of the city, accommodated artillery units.

Those artillery units practiced on a range south of town, requiring troopers regularly to ride through the city. A cavalry regiment that organized in Indianapolis had grounds north of Indianapolis, and a unit of African American soldiers, organized east of the city at Camp Frémont, named after Union Gen. John C. Frémont, Republican presidential nominee from 1856 who had called for emancipation early in the war. Other camps located outside the city were Camps Shanks and Joe Reynolds, named for Indiana commanders.

In addition to rendezvous camps and garrison barracks, authorities operated other installations related to the war effort. Gov. Morton established a state arsenal to refurbish arms and fabricate bullets and gunpowder for use by Union armies. Initially located in a building south of the State House on Washington Street, state officials moved it to a building immediately north across from the capitol building on Market Street. The dangerous proximity of a facility making gunpowder to the seat of state government prompted its relocation to the east of the city. In 1862 Congress authorized the construction of a in the city. Located on the eastside, the facility began to function in 1863.

In 1862, state authorities concerned about the welfare of transient soldiers passing through Indianapolis established the Soldiers’ Home to provide shelter, medical care, and meals. Initially located just south of the railroad depot, officials relocated it south and west of West Street. Here, the state and private individuals organized by the Indiana Sanitary Commission provided thousands of meals daily. As well, commanders held political prisoners in its stockade. As an adjunct, state officials operated a Women’s or “Ladies’” Home on Virginia Avenue for the wives and children of soldiers. During the war, military authorities also took over the City Hospital to care for sick and wounded soldiers, as well as Confederate prisoners from Camp Morton.

Finally, the U.S. Army maintained various headquarters offices in buildings in the city’s downtown for a multiplicity of army commands: district command, post command, Provost Marshal General’s Bureau, quartermaster, and commissary offices, etc. These locations changed as office-space requirements and other factors arose. Officers and enlisted men called on these offices in the course of their duties.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.