The history of civil rights in Indianapolis is intertwined with that of the larger African American struggle for equality in the United States. The points at which the two histories intersect can be found in the city housing, schools, and public accommodations.

From 1816 until the the majority white population regarded African Americans in Indiana, like those throughout the United States, as inferior. As such, the lives of African American residents of Indianapolis were severely proscribed by prejudice, segregation, and other attributes of third-class citizenship. They were denied the right to vote, excluded from the state militia, subjected to physical and verbal abuse, in peril of being kidnapped and sold into slavery, barred from public schools, excluded from trade union membership, and prevented from testifying in court.

Conditions such as these prompted the first efforts on behalf of civil rights in Indiana. The (or Quakers) frequently condemned racial discrimination in the city and state. In 1851 one of several African American state conventions met in Indianapolis. Its president, John G. Britton, called upon whites to recognize African Americans’ entitlement to basic citizenship rights. Such efforts, however, had little effect.

The Civil War and emancipation changed this situation. Consequently, the years immediately following that conflict were marked by renewed action to secure rights heretofore denied African Americans. In 1865 the first of two postwar African American conventions met in Indianapolis to discuss ways of repealing “the unwholesome and tyrannical laws which have bereft us of the rights guaranteed other American citizens.” The first fruits of their labors were the rights to present testimony in court and to serve on juries. This victory was followed in 1869 by the right to vote and hold public office. Legislation was also adopted that established public schools for African American children. In Indianapolis, African Americans gained the right to equal treatment on city streetcars.

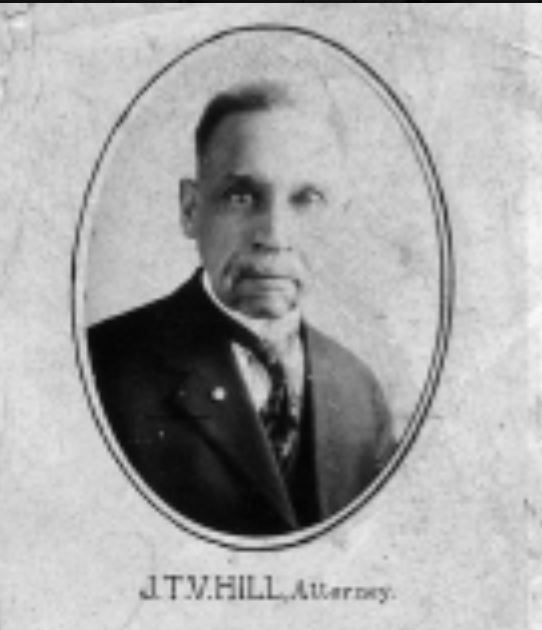

While the period 1865 to 1900 was marked by real progress in some areas, it was also clear that much remained to be done. Despite constitutional guarantees and the adoption of a state civil rights law by the General Assembly in 1885, discrimination against African Americans continued virtually unabated. Two cases involving prominent Black residents and Charles H. Stewart captured local attention. Hill, the first African American attorney in the city, brought suit in 1890 when he was refused service in a “white” restaurant. Four years later, Stewart, an African newspaper publisher, sued an elevator operator in a local hotel for assault and battery while being forcibly removed from the elevator. Although both men won their cases, neither case resulted in a major test of the stated civil rights law.

Civil rights in Indianapolis worsened significantly in the 1920s with the rise of the . The Klan dominated city government, and the City Council, under pressure from white civic groups, adopted a zoning ordinance designed to prevent African Americans from purchasing homes or living in white neighborhoods. Many public facilities were also segregated. Although the Indianapolis branch of the NAACP successfully challenged the constitutionality of the ordinance, segregation in the city housing, restaurants, parks, employment, theaters, hospitals, and public schools remained in force.

In the 1930s , an African American member of the state legislature from Indianapolis, initiated other challenges to segregation. At the 1933 session of the General Assembly Richardson proposed bills prohibiting discrimination in state public works projects and opening the state militia to Blacks, both of which were passed; although voters approved the militia bill in 1936, obstacles remained to enroll Blacks in the National Guard until 1941. Richardson also co-sponsored a bill with six other legislators in 1935 to prohibit racial discrimination. The attitudes and delaying tactics of white legislators defeated his bill, however.

By the 1940s Indianapolis had the reputation of being one of the worst offenders against equal rights among American cities. African American workers encountered discrimination in job opportunities and union membership. During Black servicemen were barred from local USO facilities as well as from white restaurants and hotels. In one instance five African American waitresses quit their jobs in an Indianapolis chili parlor when the manager refused service to Black soldiers.

World War II also heightened Black awareness of racial discrimination in employment and public accommodations. African Americans demanded fulfillment of the freedoms for which they were fighting. Their improved overall economic situation at home and an expanded middle class also made African Americans in the city and state more assertive of their rights. This more militant attitude paved the way for an all-out assault against racial discrimination in Indianapolis after the war.

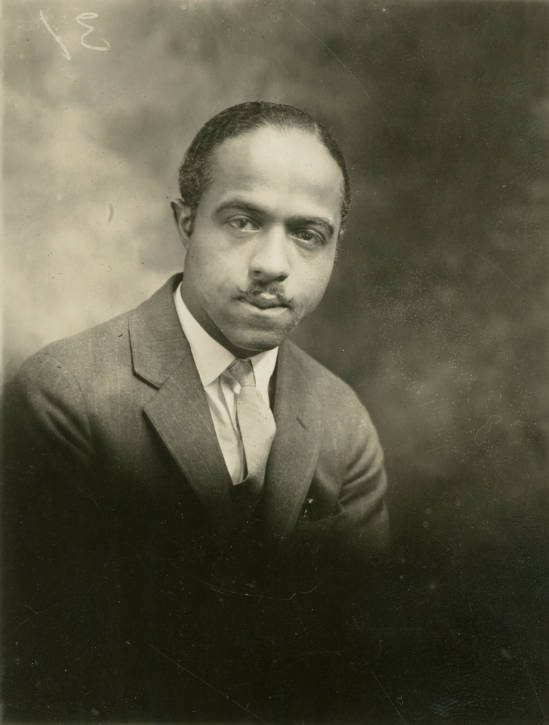

The Indianapolis branch of the (NAACP) under the leadership of played a particularly important role in the postwar fight for civil rights by its location in a city that was the state capital and had the largest African American community in Indiana. Many members of the Indianapolis NAACP were also members of Starling W. James’ , a local organization with objectives similar to the NAACP.

Representatives from 18 Indiana branches of the NAACP at the Fort Wayne civil rights gathering in October of 1947. Willard B. Ransom (ninth from right) was elected state leader of the NAACP at this meeting. Credit: Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Indiana Historical Society View Source

In 1945 civil rights activists in Indianapolis scored their first postwar legislative success with the Indiana General Assembly’s passage of the weak, noncompulsory, though much-publicized Fair Employment Practices Act. This legislation authorized the State Labor Commission to work toward eliminating discrimination from the workplace but did not specify penalties for noncompliance. Four years later, in 1949, activists scored their second major victory with a law abolishing segregation in public education.

Meanwhile African Americans in the immediate postwar years undertook nonlegislative means of ending discrimination and winning access to places of public accommodation, spearheaded by the Indianapolis NAACP It was joined by a loose coalition of NAACP branches in other Hoosier cities, the Federation of Associated Clubs, African American social and fraternal organizations, labor unions associated with the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO), the Jewish Community Relations Council, and a variety of church-related groups. In the absence of strong government enforcement, these private groups began a largely indigenous, nonviolent campaign to secure compliance with the 1885 civil rights law. Meetings were held with managers of establishments that barred African Americans to persuade them to observe the law. Unsuccessful negotiations were followed by nonviolent direct action, usually by racially mixed groups, to secure service in those establishments.

In 1946 the CIO mounted the first concerted attack on discrimination in local hotels and restaurants. The following year a local group, under NAACP leadership, began a more vigorous crusade against racial discrimination in the city’s restaurants. There were also challenges to discrimination in places of recreation and amusement, such as , The Federation of Associated Clubs opened many movie theaters to African Americans through negotiations with the managers of these establishments.

The 1950s and 1960s witnessed increased local activity in the civil rights movement. Recognizing the need to address civil rights, the City Council in 1952-1953 created the , an advisory group to the mayor on civil rights matters. Consisting of community leaders, the commission worked to promote “amicable relations” in the community, mediate disputes, and integrate local institutions. Others also joined in the push for civil rights. Local minister , chair of the Human Rights Commission in 1961-1962, was a staunch advocate of integration. The also participated actively in the civil rights movement. Likewise, the , dedicated to the protection of Bill of Rights guarantees, was founded in 1953 in response to the racial discrimination of the 1950s.

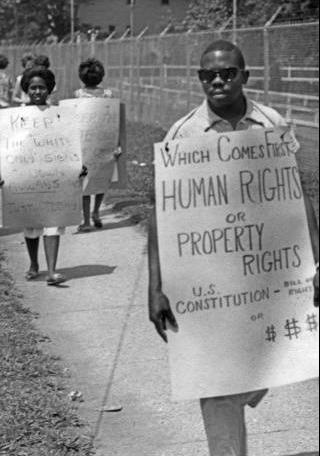

Despite some success in challenging segregation, social activists recognized the need for a stronger civil rights law. Their efforts met with repeated frustration and failure until 1961 when the Indiana Conference on Civil Rights Legislation was formed in Indianapolis. By the mid-1960s intense lobbying by this group as well as public demonstrations in the city led to legislation creating the Indiana Civil Rights Commission, a stronger law banning discrimination in public accommodations, a fair housing law, and repeal of Indiana’s prohibition against interracial marriage.

Despite the existence of a strengthened 1949 law, patterns of racial segregation in the persisted into the 1960s. The NAACP filed suit in 1968, and the resulting 1976 desegregation order by Federal Judge is still in effect today, although somewhat modified in 1993 by the school system’s program. Although racism is not dead in the city and surrounding suburbs, its overt manifestations are not as visible and occur less frequently than in the past. That such is the case due in large part to the Indianapolis civil rights movement.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.