Child welfare services have evolved throughout Indiana statehood, with a mix of public, nonprofit, and faith-based entities playing important roles in service delivery. Child indenture in the U.S. began in 1636 Massachusetts and remained a common practice, as well as the basis for child care laws, through the 19th century. Indiana law hailed from this tradition. In the 19th century, the legal responsibility for destitute children fell to township trustees. If families were willing to part with their children, or if children did not have functional parents or parents at all, minors could be apprenticed or “bound out.”

As the state established its first benevolent institutions for the deaf (1843), insane (1844), and blind (1845), it assumed no responsibility for dependent children unless they were members of one of the special classes. Orphaned Indiana children, or children whose parents had abandoned or unreasonably neglected them, were either bound out as apprentices or consigned to live in county poorhouses. The care of indentured children could be uneven at best and those who lived in poorhouses received little education and cohabitated with adult inmates.

In 1852, Indiana updated its child indenture law to create a minimum standard of care for bound-out children and an enforcement mechanism for that level of care. The 1852 law required that children receive basic education in common schools, not work more than 10 hours per day, and must be emancipated upon reaching the age of adulthood or a female child’s marriage. Several authority figures could authorize indenture agreements: a parent, guardian, township trustee, or the child him or herself if over the age of 14.

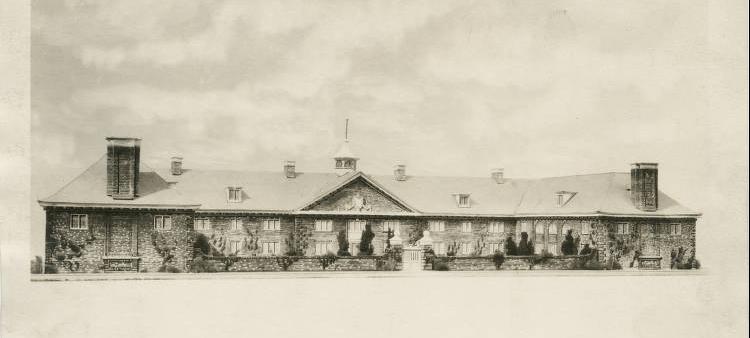

Voluntary associations lobbied for changes to the child indenture law, including the Widows’ and Orphans’ Asylum and Indianapolis Benevolent Society. After the 1860s, child welfare awareness rose around the country and several states–including Indiana–established orphanages and mandated the removal of children from poorhouses. Several orphanages opened in response to the national movement, including the General Protestant Orphan Home (), (IAFCC) established by Quaker women, and .

In 1889, the Indiana General Assembly created the Board of Children’s Guardians (BCG), a government organ run by volunteer citizens—and the first in the country. The governing board of six appointed citizens, three men and three women, had the authority to assume custody of children via court order. Local courts heard extreme cases of child abuse on a case-by-case basis. By the 1920s, similar boards operated in most states.

The Local Council of Women supported the Juvenile Court Law, which passed in 1903, making Indiana just the third state to create a juvenile court. Indiana’s Juvenile Court arose directly out of the BCG and voluntary probation system. It built upon the BCG foundation and presumed the state must act as guardian when children’s circumstances could develop into crime. Several outcomes could result from court proceedings. The court could drop charges, suspend sentences, and return children to their homes on probation, or send children to private or state institutions. About one-third of children were released on probation under the charge of a volunteer probation officer. The juvenile court judge, George Stubbs, recruited volunteer probation officers from churches and social services agencies such as the , , and the Charity Organization Society. Within 18 months, he had 75 women and 230 men supporting juveniles as role models.

Child welfare, also known as child saving, was a key element of Indiana’s public policy. One of the most successful child welfare agencies in Indianapolis, the Children’s Aid Association (CAA) formed in 1905, was born out of several related child welfare initiatives: the Board of Children’s Guardians, the Juvenile Court, and the Volunteer Probation Officers Association. The CAA’s probation and visitation functions absorbed those of the Board of Children’s Guardians (BCG). The CAA through the 1910s reported that it lowered crime, increased health, and saved children from poverty, imprisonment, or institutionalization, thereby producing constructive citizens. The CAA’s initiatives, especially pure milk stations, steadily reduced infant deaths in the city. Between 1907 and 1916, infant mortality dropped almost in half.

The federal government drew national attention to child welfare concerns at its landmark 1909 White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children. President Theodore Roosevelt opened with a discussion of a widow unable to support her children. Child welfare experts had been arguing for keeping children with their mothers and out of orphanages and foster homes. The key debate revolved around the proper source of support, nonprofit organizations or government. The White House Conference provided the spark for a decade of unprecedented change in public welfare, including Indianapolis.

The BCG dissolved when 1930s federal welfare legislation took effect and in 1937 became part of the Marion County Welfare Board and Department of Public Welfare. The National Welfare Act of 1936 gave the Marion County Department of Public Welfare responsibility for providing direct care and services to dependent, neglected, and disabled children and children at risk of becoming delinquent.

Since the 1960s, federal public welfare legislation, Indiana child welfare laws, and the intervention strategies employed by service providers have continued to reflect society’s complexity. The evolution in services has reflected high divorce rates, increased drug and alcohol addiction, mental health and suicide, the AIDS crisis, backgrounds of abuse, LBGTQ+ at-risk youth, family homelessness, and incarceration of parents. A mix of public and private organizations continues to provide child welfare advocacy and protection.

The Indiana Department of Child Services, part of the Indiana state government, leads the state’s response to allegations of child abuse and neglect and facilitates child support payments. Indiana Children’s Advocacy Centers, founded in 1999 as part of the National Children’s Alliance, promotes the development, growth, and sustainability continuation of children’s advocacy centers in the State of Indiana. The Children’s Bureau provides the most comprehensive prevention, intervention, and support services to Marion County children. Other safety-net and support organizations include lutheran child and family services, , , Indiana Center for Children and Families, Adult & Child Services, , Fathers and Families, Holy Family Shelter, , YMCA, and .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.