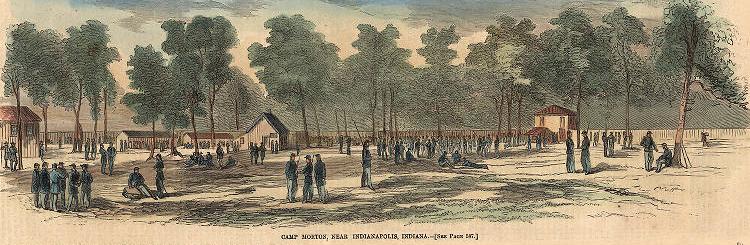

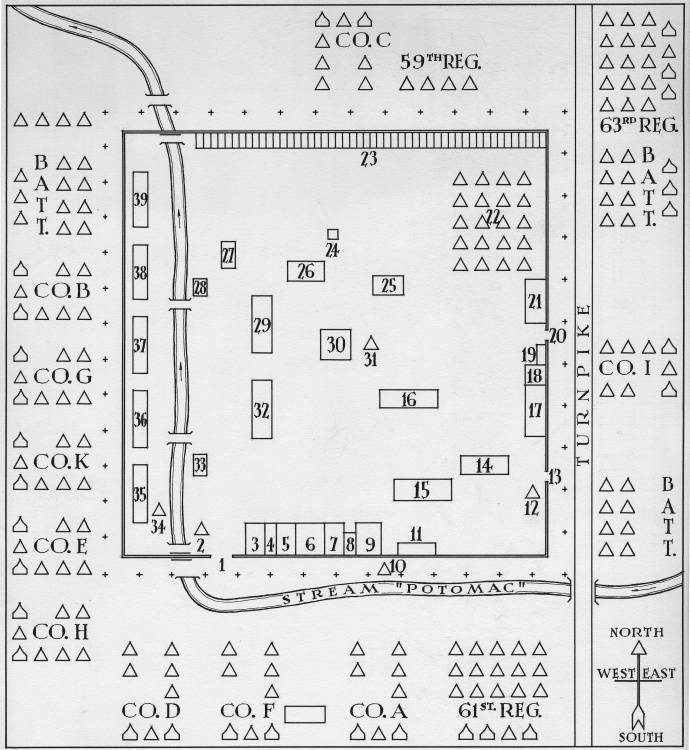

Camp Morton was a military installation located north of Indianapolis. Originally a volunteer-troop rendezvous camp, military authorities converted the facility to a prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederate troops.

In the first weeks of the American (1861-1865), thousands of volunteers from around Indiana converged on Indianapolis to organize into military units to be accepted into the United States Army. In May 1861, state officials converted the , located one mile north of the city near today’s 19th and Delaware Streets, into a military rendezvous camp, where officers would organize volunteers into companies and regiments and drill them preparatory to entraining to the front.

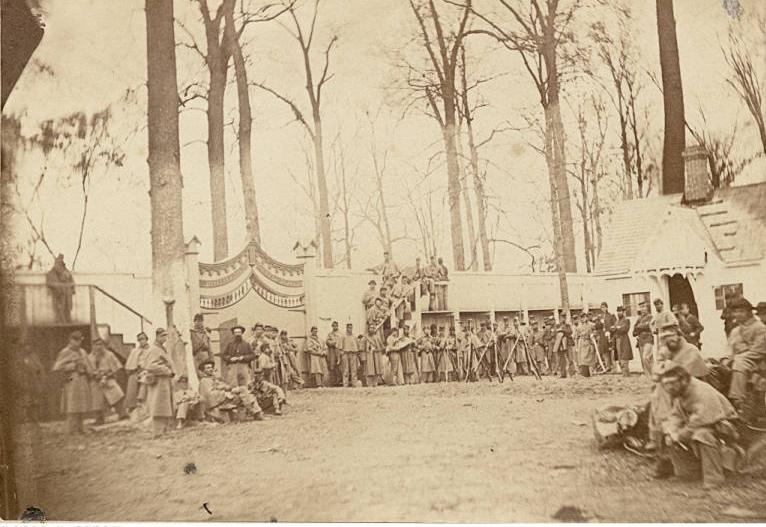

Men occupied horse, cattle, and swine barns for shelter. Soldiers dubbed the makeshift camp, Camp Morton, after Governor . As most people believed the Confederate rebellion would be suppressed quickly, little thought was given initially to long-term accommodations for troops. However, the Union defeat at the first battle of Bull Run in July 1861 made real the probability of a long conflict. Thereafter, camp commanders constructed rough barracks to replace cow sheds.

In February 1862, the significant Union battle victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee prompted the surrender of a rebel army of 15,000 soldiers. For the first time in the conflict, Union military authorities were confronted with the task of housing large numbers of prisoners. They asked state governors north of the Ohio River to organize accommodations. From the rebellion’s outset, federal government leaders had decided to treat the rebels not as traitors but as prisoners of war, entitled to treatment as lawful combatants.

Gov. Morton responded promptly by converting his namesake rendezvous camp into a prison camp. Around the end of February, about 3,000 bedraggled, ill-clothed and fed Confederate prisoners arrived by train in Indianapolis. More were held temporarily in Lafayette and Terre Haute. Troops in the city began to serve as a prison camp garrison, mounting watch on the camp stockade walls and patrolling the perimeter.

Local residents treated the prisoners as wayward, misguided youths who might be persuaded by kindness to renounce rebellion and return to proper allegiance. But the ideological commitment of the prisoners—enlisted men all, as their officers were held in Johnsons Island prison camp in Lake Erie—dispelled such sentimentality. The War Department took over the management of the camp. By late 1862, most Confederate prisoners-of-war in Camp Morton had been shipped south as part of prisoner exchanges, leaving it mostly empty. However, in 1863 Union victories in the West led to the camp filling again to the point of overcrowding.

Historians have long debated the living conditions in federal prisoner-of-war camps during the Civil War. “Lost Cause” mythology promoted by Confederate apologists has long supposed that the camps were officered by cruel, vengeful tyrants who cared little for the welfare of the rebel prisoners. Such cruelty, they argued, prompted mistreatment in the form of deliberately starving prisoners and providing bad medical care. Recent scholarship on the camps, including Camp Morton, concludes that federal officers who ran the camps were not deliberately cruel. The Commissary General of Prisoners, a bureau of the War Department, took careful steps to house, feed, and provide care to the Confederates. Prisoners received the same high-calorie daily ration as did Union troops. Officers sought to remedy sewage and drainage problems in the camps and provided medical care.

That said, deaths among the prisoners were numerous. Camp Morton had the highest mortality statistics of the camps administered by the War Department. Overcrowding, rampant disease among the prisoners, and lack of medical knowledge among medical staff were among the causes. Pneumonia was the chief killer, followed by diarrhea/dysentery, and malaria. Disease spread readily in the crowded barracks, which had dirt floors. Water supplies became polluted by sewage.

Despite the efforts of Camp Morton officers, prisoners died in large numbers, especially when the exchange cartel broke down when Confederate authorities refused to treat captured African Americans as prisoners of war. Crowded camps became increasingly crowded. In May 1864, as a negotiation tactic, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton cut the prisoners’ daily ration. In early 1865 the prisoner exchanges resumed.

Camp Morton and other prisoner-of-war camps holding rebel troops were targets of northern Confederate-sympathizers’ efforts to release the prisoners. Starting in late 1863, secret organizations linked to the plotted attacks on the camps. The most serious effort in the city occurred in August 1864, when Sons of Liberty conspirators led by Indianapolis businessman planned an armed uprising in Indiana and the city to release Confederate prisoners. The freed rebels would be armed and, with their liberators, run rampant in the North. The uprising would, conspirators hoped, force Union troops to be diverted to the North. The effort collapsed at the last minute when Democratic politicians who learned of the plot intervened. A number of rebel troops managed to escape from Camp Morton by means of tunnels and breaches of the stockade walls.

At the end of the war, Camp Morton and other prisoners of war camps emptied and the southern troops returned home. The campsite reverted to use as the state fairgrounds.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.