Indianapolis was introduced to the “air age” in the late 1800s with hot air balloon ascensions and parachute jumps. On July 15, 1889, five special trains carried hundreds of spectators from Indianapolis to to watch “this breathtaking spectacle.”

Aerostatic or balloon competition made its first appearance in 1909. On June 5, the first U.S. National Balloon Race launched from the as yet unfinished . An estimated 75,000 persons watched six of the nine entries lift-off, including the local favorite, the , piloted by , one of the four Speedway owners, and George Bumbaugh, Indianapolis balloonist. The was forced down near Ruskin, Tennessee, some 235 miles from Indianapolis. The race winner landed near Payne City, Alabama, 378 miles from the starting point. Another, much smaller balloon, the , piloted by , noted Indianapolis physician and scientist, and Russ Irvin, local aviator, won the handicap section of the event, landing at Westmoreland, Tennessee, about 40 miles northeast of Nashville. Two more National Balloon Races started from the city on September 17, 1910, and July 4, 1923.

The week of June 13-18, 1910, was “Aviation Week” in Indianapolis, the first licensed aviation meet in the United States. Attending were noted aviators from all over the country, including Wilbur (born near Millville, Indiana) and Orville Wright, who on December 17, 1903, had both flown the world’s first successful airplane. Among the entries were three Indianapolis pilots: Russell Shaw and Melvin Marquette, who entered homebuilt planes, and Joseph Curzon, with a French-built craft.

Included in the week’s numerous events were demonstration flights of various models, speed record attempts, and several races of varying lengths. Notable among these was an event in which eight planes competed, at that time the largest number of planes ever in the air at the same time. Several records were set, including a new high for a plane carrying two persons when two men succeeded in remaining aloft for 12 minutes. The highlight of the meet, however, was the setting of a new world’s altitude record. On June 13, the Wright brothers’ demonstration pilot, Walter Brookins, reached a height of 4,384½ feet above the ground, far exceeding the existing record.

Despite all the excitement of the balloons and the still relatively unproven airplanes, most Hoosiers were more interested in automobiles and auto racing. While the Aero Club of Indianapolis kept its clubhouse inside the Speedway track and did a moderate amount of both airplane and balloon flying, no serious activity took place at the field until World War I. Early in 1918, the U.S. Army built a large aircraft and engine repair facility south of the track to repair all aircraft and engines east of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio rivers. Two large shop buildings, one for airplanes and one for engines, along with offices and barracks for military personnel, were set up on Main Street in Speedway City (the town of ) and new hangars were built on the flying field inside the track. Among the base’s principal activities were the testing, repairing, and modifying of Liberty aircraft engines, many rebuilt by the Allison Engineering Company located across the street from the repair shops.

Probably the most exciting event in Indianapolis’ early aviation history was the October 24, 1919, arrival at the Motor Speedway of the 18-passenger Lawson Airliner, at the time the world’s largest passenger plane. On the return leg of a round trip from Milwaukee to New York, the plane carried nine passengers and a crew of two, including pilot Charles E. Cox (who would later become superintendent of the Indianapolis Municipal Airport).

Large crowds of excited spectators braved 10 days of continuous rain to inspect the giant plane, which, too large to be hangared, remained outside during the entire Indianapolis stay. The rain finally stopped, and, on November 6, the plane and its weary passengers and crew finally made a slow and harrowing takeoff from the water-soaked field.

The Indianapolis Aerial Association opened the city’s first public landing field in July 1920. The company planned to offer flying instruction, passenger rides, and regular service to large cities within a 200-mile radius of Indianapolis. The venture, a few years ahead of its time, quickly faded into oblivion.

Crawford Field, an attempted revival of the Aerial Association, opened in 1922. The company had operated for almost a year when an unbelievable set of circumstances forced it out of business. Both of its planes were lost on the same day: one crashed near Bloomington and the second was lost when the company hangar burned down, the result of a hunter shooting at rabbits and igniting the grass around the hangar.

The first military field in Indianapolis was officially opened on May 7, 1922. Located northeast of Lawrence at , the field was named Schoen Field in memory of Army Lt. Carl J. Schoen, an Indianapolis pilot who was killed in action over France during World War I.

The facility served as an intermediate landing field and reserve airdrome for years and also as a temporary home for the air unit in 1926-1927. The U.S. Army closed it in 1945, the 10th Air Force reactivated it in 1947. However, the short, sod runways proved incapable of handling the large military craft using the field, and it was permanently closed in 1950. The field later became the site of the

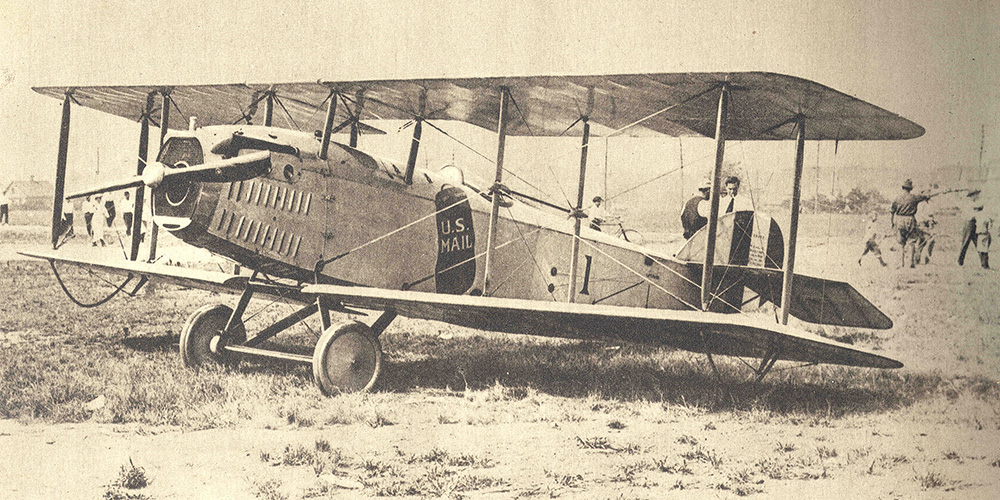

In 1922, the first airmail arrived in the city. On May 29, eight planes of the U.S. Air Mail Service flew in from Chicago to demonstrate the possibilities of direct air mail connections with other parts of the country. (At the time, the only government air route was New York-Chicago-San Francisco.) Their landing in a field just west of aroused considerable public interest, and numerous city and post office air service discussions ensued. However, another five and a half years would pass before Indianapolis would join the airmail system.

The first local scheduled air service began December 17, 1927, when the Embry-Riddle Company opened an airmail route between Cincinnati and Chicago via Indianapolis, operating from Cox Field. By the end of the year, the company had carried 1,043 pounds of mail over the line. Passenger service began early in 1928.

The second airline to serve the city was Capitol Airways, which, on October 22, 1928, began an Indianapolis-Fort Wayne-Detroit passenger and express service from Capitol Airport. By February 1929, the company added routes to Louisville via French Lick and to Chicago via South Bend. In spring 1929, however, all services were temporarily discontinued due to poor connections with other airlines at the three destinations and permanently dropped in the fall for financial reasons.

The first major airline to serve the city was the highly promoted and long-awaited coast-to-coast Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT), which began scheduled service July 7, 1929. A novel operation, the new company sent its passengers overnight via the Pennsylvania Railroad from New York to Columbus, Ohio. (This rail segment bypassed the “killer stretch” over the Alleghenies, which had claimed the lives of many airmail pilots in the early twenties.) Early the next morning, the passengers boarded the famous Ford trimotors for the air trip via Indianapolis and St. Louis to Waynoka, Oklahoma, where they transferred to the Santa Fe Railroad for the overnight trip to Clovis, New Mexico. Then, on the second morning, they boarded another Ford for the balance of the trip to Los Angeles.

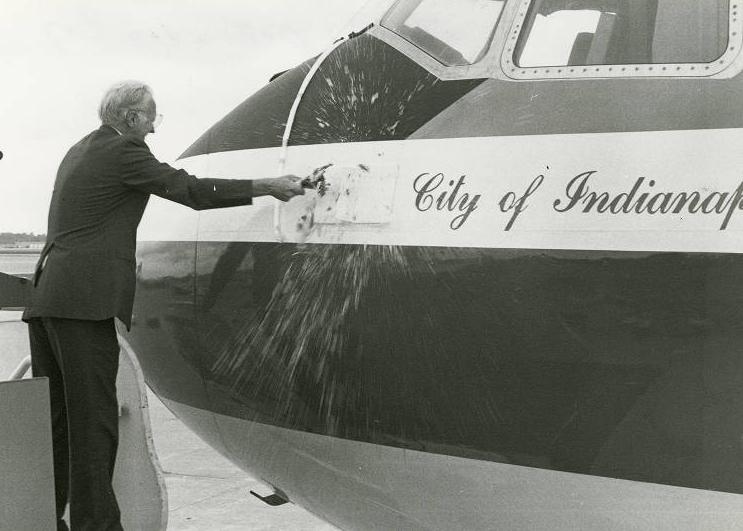

The first westbound TAT trimotor landed at on the morning of July 8 and, following an appropriate but short welcoming ceremony, departed for St. Louis and the West Coast and its permanent niche in American airline history. Some three weeks earlier, on June 19, a TAT Ford on a route survey and pilot check flight stopped at Stout Field. The city’s mayor, postmaster, and TAT officials christened it the City of Indianapolis. Ironically, the plane suffered a fatal crash on the same field while attempting a landing during a heavy snowstorm just six months later, on December 22, 1929.

To handle its Stout Field passenger and express operations (a mail contract was not obtained until September 30, 1930), TAT built a brick and concrete U-shaped terminal with two wings, one for offices and the other for a garage to store the “Aerocar” trailer used for local passenger transportation. A fireplace-equipped passenger lounge and ticket office occupied the central part of the building, and a metal canopied walkway extended from the lounge onto the concrete loading apron.

Adjacent to the south was the large new hangar of the Curtiss Flying Service, where any required emergency maintenance could be performed. Both the former terminal and the hangar were used long after their creation by the ground units of the Indiana Army National Guard.

In 1929, a new aeronautical mania, endurance flying, both solo and refueled, swept the country. Among the best-known midwestern flights were those by two Indianapolis pilots, Lts. Walter Peck and Lawrence (Gene) Genaro, in the , an all-metal plane similar to those used by the Embry-Riddle airline. Their two record attempts from Hoosier Airport came to naught when continuing fog and rain prevented refueling. In the end, despite a perfectly functioning plane engine, the two pilots had to settle for a 149-hour and 36-minute mark, far short of the existing record.

New airlines began serving the city in the 1930s. Embry-Riddle became part of American Airlines in November 1930, and Eastern Air Lines began service in June 1934. In 1939, the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Authority opened its Experimental Station at the Indianapolis Municipal Airport. The new technical center concentrated on the development of improved aircraft radio equipment, radio ranges, instrument landing systems, and aircraft lighting.

During World War II, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation built one of the nation’s largest propeller plants in the city and the of General Motors added several new engine manufacturing plants. Allison also developed a flight test center at Weir Cook Airport for testing engines for numerous fighter and other aircraft.

Following the removal of World War II restrictions, local flying interest reached new highs. Attempting to fulfill the “plane in every garage” forecast, hundreds of former servicemen took flight instruction, private aircraft sales boomed, and several new commercial and private airfields were developed to handle the increased activity.

Commercial aviation grew apace as several new airlines began serving the city. These included a new type of carrier, the air freight lines. Carrying cargo only, these companies hauled anything that would fit inside the planes, including flowers, heavy machinery, furniture, racehorses, and perishable foods. In the eighties, a new version of these lines developed—the small parcel carriers, offering overnight delivery services to points nationwide. Two of the country’s largest, United Parcel Service and Federal Express, began serving the city.

Another new type of operation for the time was the helicopter, which entered the local scene in the 1950s. Several law enforcement agencies and local companies have made extensive use of copters and one of the premier public heliports in the country has since begun operation in downtown Indianapolis.

The Indianapolis Municipal Airport began operations in 1931. The field was renamed Weir Cook Memorial Airport in 1944 in honor of a World War I fighter ace. In 1976, with the opening of a new building to serve international flights, the field was designated . By the early 1990s, the facility accommodated over 6 million passengers annually.

One major addition to the Indianapolis International Airport came in the early 1990s with the creation of plans with the . While the proposal called for an $800 million facility, only part of the plan was executed due to United Airlines’ early 2000s financial struggles. Nevertheless, the IAA claimed the maintenance center for the Indianapolis International Airport site, renaming it the Indianapolis Maintenance Center.

In 1988, Federal Express (FedEx) opened its Indianapolis hub with a little over 300 employees. expanded the facility in 1998. The 1998 expansion, the largest in FedEx history, made Indianapolis the second largest in the nation. In 2005, FedEx proposed another 400,000-square-foot expansion. With this expansion, the Indianapolis hub had a sorting capacity of 99,000 packages per hour and employed nearly 4,000 people. As FedEx celebrated the hub’s 30th anniversary, the company announced that it would invest another $1.5 billion to make further improvements and expansions over the course of the next seven years.

In 2008, the Indianapolis International Airport opened a new $1.1 billion terminal for use. By the late 2010s, the new space had allowed the airport to grow to over 9.5 million passengers per year and, in 2018, add the first nonstop transoceanic flights out of Indianapolis (the flight went to Paris). The airport regularly has been named one of the best airports in North America. In addition, with the second-largest FedEx Express hub in the world on its property, the Indianapolis International Airport has become one of the Top 10 busiest airports for cargo transit.

FURTHER READING

- “Aviation in Indiana.” The Indiana Historian, June 1998. https://www.in.gov/history/files/aviationinindiana.pdf.

- Untold Indiana. “Aviation.” https://blog.history.in.gov/tag/aviation/.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Marlette, J. & Opsahl, S. (2021). Aviation. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 9, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/aviation/.

MLA:

Marlette, Jerry and Sam Opsahl. “Aviation.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/aviation/. Accessed 9 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Marlette, Jerry and Sam Opsahl. “Aviation.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Mar 9, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/aviation/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.