Indianapolis was an early center for automobile manufacturing and design. For a brief period early in the 20th century, it seemed that Indianapolis would rival Detroit for leadership in the American automobile industry. Around 1910, Indianapolis was considered the fourth most important city in automobile manufacturing, following Detroit, Toledo, and Cleveland. Unlike Michigan manufacturers, however, none of the Indianapolis firms ever achieved mass production.

Perhaps as many as 90 makes of the automobile and five motorcycles were manufactured in Indianapolis, most of them in small numbers for a brief span of years. The Atlas-Knight (1912-1913), Economycar (1914), Hoosier Scout (1914), and Pathfinder (1911-1918) were easily forgotten except by their owners.

Three of America’s most elegant automobiles of the 1920s were designed and manufactured in Indianapolis—, , and . They, however, were intended for the few and the rich, not the typical motorist.

With very few exceptions, the Indianapolis firms were seriously undercapitalized because the automobile manufacturers of Indianapolis received little support from local bankers or investors of wealth. Raising money was a constant worry, even for successful automakers.

Early Automobile Makers

Beginning with the pioneer efforts of in the late 1890s, local inventors and promoters struggled to develop automobile manufacturing. For several decades, they enjoyed considerable success. Waverly Electric was the first to produce more than a handful of vehicles, making battery-powered cars of limited range, suitable only for use in town, from 1898 to 1909.

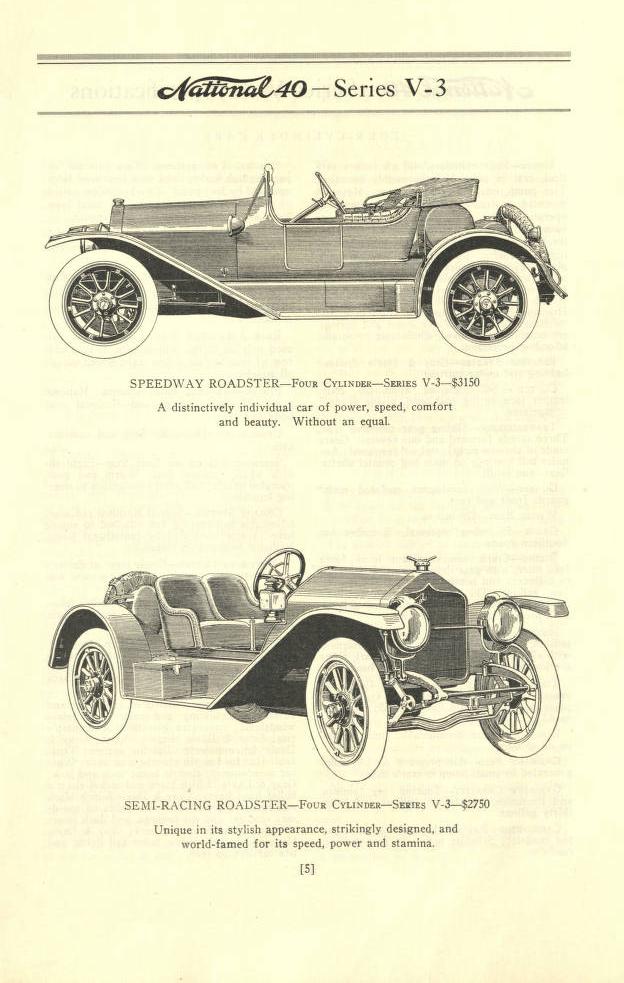

National Motor Car Company

and Charles E. Test, successful bicycle-chain manufacturers, established the National Auto and Electric Company in 1900 and changed its name to National Motor Car Company three years later. entered the business with an electric automobile in 1902 but suffered several financial reverses. Newby reluctantly introduced a gasoline-powered car in 1904 but continued to market electrics until 1911. National deliberately concentrated its efforts on high-quality, expensive cars and never attempted mass production. Despite its conservative design practices, National enjoyed great success on the race tracks between 1909 and 1912 but withdrew from competition after winning the second .

Overland Auto Company

The Overland Auto Company began in Terre Haute and moved to Indianapolis in 1905 with the financial support of , a local buggy maker. Near bankruptcy during the financial panic of 1907, John North Willys, an ambitious automobile salesman from upstate New York who contracted for the firm’s entire production, rescued Overland. Willys became president, treasurer, general manager, and sales manager for Overland and launched an ambitious expansion program. Indianapolis financiers declined to support Willys, and, in 1909, he purchased a vacant factory in Toledo and shifted Overland production to Ohio, renaming the car Willys-Overland.

Willys hoped to challenge Ford’s dominance of the low-priced field and produced 5,000 vehicles in 1909, the firm’s last complete year in Indianapolis. Three years later, Overland ranked second to Ford in production, but Willys’ extravagant ambitions eventually led to financial disaster.

Ford Motor Company

Although little noticed and never celebrated, the largest automobile producer in Indianapolis was ironically the most familiar name in the industry—. Henry Ford developed an extensive network of branch assembly plants to “build” the Model T manufactured in his giant factories near Detroit. High railroad charges for finished vehicles encouraged the use of regional plants that could build cars for dealers within a few hundred miles.

Twelve “semi-knocked-down” cars could fit in a standard boxcar, while special auto-carrying boxcars had space for only three or four fully-finished vehicles. In 1903, when Ford began taking orders for its legendary Model-T, the Indiana Auto Company at 34-36 Monument Place in Indianapolis processed one of the earliest orders. In 1914, as part of a plan to decentralize operations and save shipping costs, Ford erected buildings on Washington Street as a regional center where cars would be assembled, sold, and repaired.

Model T production in Indianapolis began in 1914 and, during the early 1920s, exceeded 25,000 vehicles a year. The plant shifted to Model A production in 1928, but branch manufacturing was no longer efficient in small plants so close to Detroit and thus the Indianapolis operation closed in 1932.

Cole Motor Car Company

Joseph J. Cole was a successful carriage manufacturer who shifted into automobiles in 1908-1909. Harvey S. Firestone of the tire company provided much of the necessary capital for the , which pushed production to 2,000 vehicles a year by 1912. Cole promoted his cars in every way possible, from entering road races to advertising on a giant balloon. He also advertised them with now-dated stereotypes such as “The Man’s Car That Any Woman Can Drive”.

Cole rejected offers from William Durant to become part of General Motors and competed directly with Cadillac in the luxury V-8 market, advertising the Cole as “The Pride of Indianapolis.” In 1919, Cole began an expensive expansion program that drove the firm into serious financial troubles during the recession of 1920-1921.

Sales dropped sharply and he closed the company rather than risk his fortune in a hopeless effort to compete with larger manufacturers. Production ceased in 1924, and the firm was successfully liquidated.

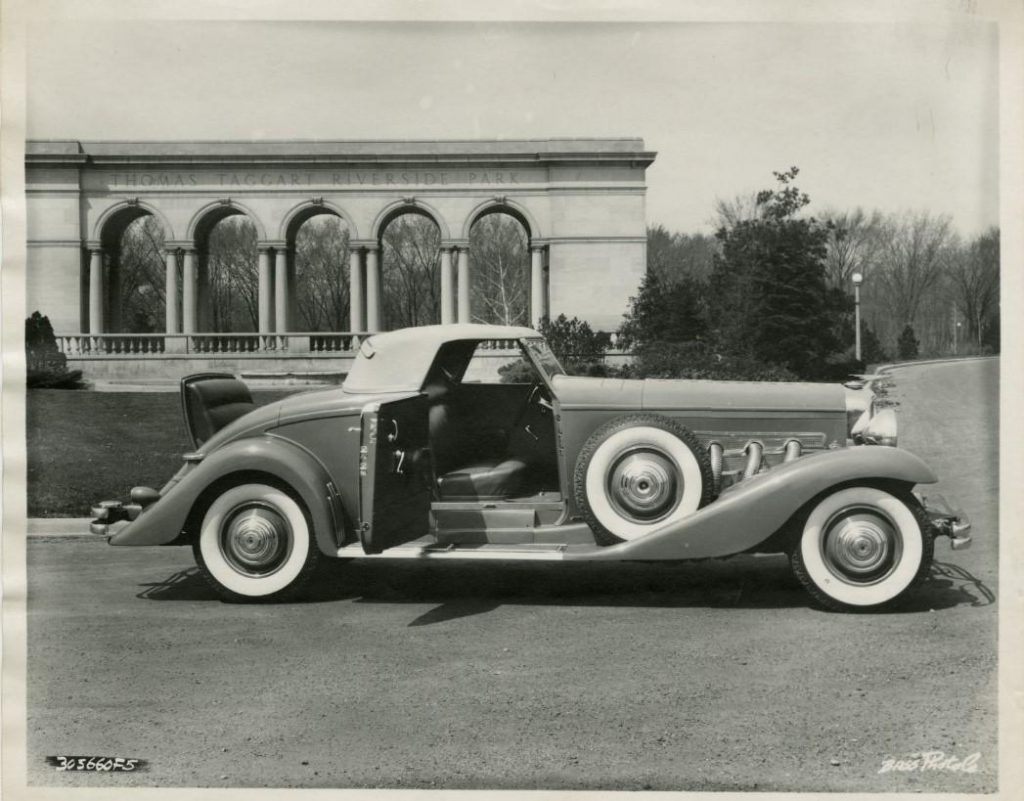

Classic Luxury Automobiles, 1920s-early 1930s

During the Roaring Twenties, Indianapolis dominated the nation in the manufacture of luxury high-powered automobiles that often cost more than a new middle-class house. Buyers of Marmon, Stutz, and Duesenberg models were people who regarded automobiles as they did their yachts, elegant playthings whose price did not matter. Depending upon the body design selected, a Duesenberg might cost nearly $20,000 in 1929 (over $300,000 in 2020).

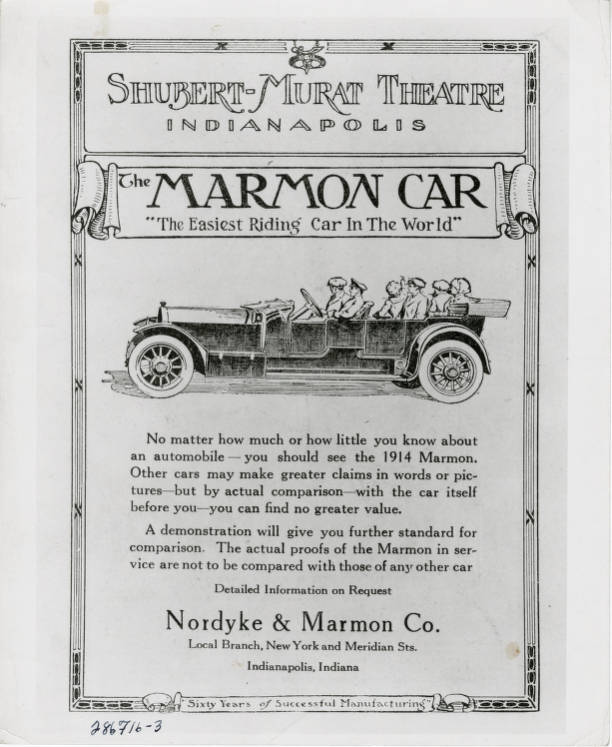

Marmon

built his first automobile in 1902, using the facilities of , the nation’s leading manufacturer of flour milling machinery. Commercial production began three years later. Marmons were always elegant and well-engineered machines, widely admired but never built in large numbers. Howard Marmon was the chief designer and engineer while his elder brother Walter looked after finance and manufacturing. Marmons excelled in both road and closed-circuit racing between 1909 and 1911. In the latter year, a Marmon Wasp won the first Indianapolis 500 at an average speed of 74.61 miles per hour.

Marmon advertised itself as “A Mechanical Masterpiece” and built virtually all of its own components, unlike most Indianapolis automobile manufacturers. The flour-milling-machinery business provided a solid financial and production base, and Marmon was successful as a car builder from its earliest years but not profitable.

George M. Williams purchased a major interest in 1924, and, two years later. the flour-milling-machinery business was sold and the firm reorganized as the Marmon Motor Car Company. The smaller and cheaper Little Marmon lasted only one year, but the powerful and elegant 8-cylinder Marmon was a great success, with sales of 22,000 in 1929. The hit Marmon very hard, and Howard Marmon’s last design, a 16-cylinder model for 1931, was a magnificent machine that very few buyers could afford. Marmon closed in 1934. Walter Marmon, meanwhile, joined with the inventor Arthur W. Herrington in 1931 to manufacture all-wheel-drive trucks under the name.

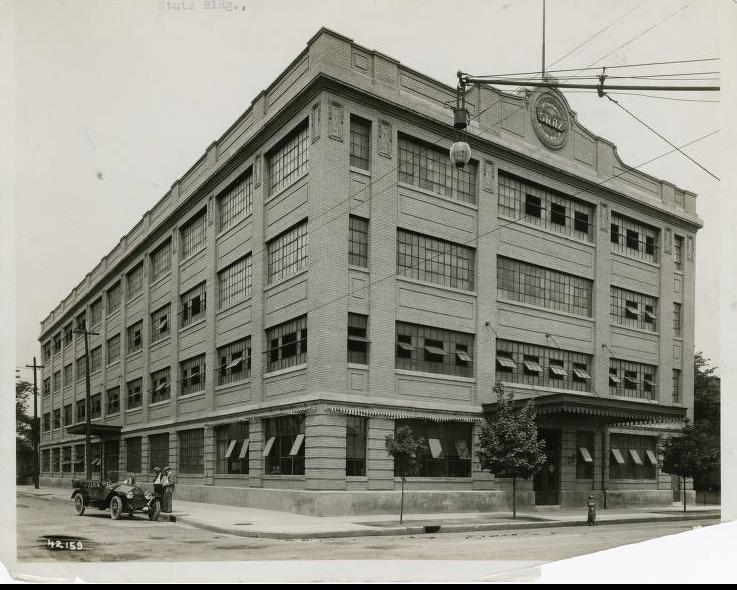

Stutz

Harry C. Stutz moved to Indianapolis from Ohio in 1903 and struggled in the auto parts business until 1911 when he hurriedly built a racing car to compete in the first 500-mile race. The Stutz finished only 11th , but it did finish and the new Ideal Motor Car Company advertised the achievement for years. The famed Stutz Bearcat appeared the following year, to immediate popularity. The Bearcat was fast, sporty, and uncomfortable as well as a car that could be raced competitively.

Known from 1913 as the Stutz Motor Car Company, Stutz expanded production to 2,200 cars by 1917 but suffered financial troubles and ownership changes which, by the mid-1920s, brought Charles M. Schwab to financial leadership and Frederick E. Moskovics to operating control. Moskovics improved both engines and body design and maintained Stutz’s popularity among wealthy lovers of fast cars, even with a 1926 model known as the Safety Stutz.

The Stutz Black Hawk of 1927 was America’s fastest production car, but the Great Depression destroyed its market and sales dropped rapidly, falling to a mere six vehicles for 1934. Stutz suspended automobile production in January 1934 and tried to keep in business with a delivery van called the Pak-Age-Car. The effort failed dismally, and Stutz was liquidated following its 1937 bankruptcy.

Duesenberg

Without question, the finest automobile ever built in Indianapolis was the Duesenberg Model J, usually ranked as the greatest of American automobiles. Brothers advanced from making bicycles to building high-powered engines for boats and automobiles.

During World War I, they prospered building boat and airplane engines for military use. With the return of peace, however, they decided to enter automobile manufacturing and moved from New Jersey to Indianapolis to further their racing ambitions. Their Model A sedans were well-designed but unprofitable, and the firm failed in 1924.

The Duesenberg brothers were more successful building race cars, winning the French Grand Prix in 1921 and the 500-mile race in 1924,1925, and 1927. Fred Duesenberg became president of the reorganized Duesenberg Motors Company and solved his financial troubles by selling out to E. L. Cord’s Auburn Automobile Company in 1926. Cord intended to challenge Stutz in the luxury high-performance field, and Fred Duesenberg designed the elegant and carefully engineered Model J, powered by a Lycoming straight-eight engine that gave a top speed of 116 miles per hour (130 miles per hour for the supercharged Model SJ in 1932).

Duesenberg built only the chassis of the Model J; buyers contracted the independent coachbuilders for the custom body they wished. Altogether, only 481 of the legendary Model J Duesenbergs were built during five years of unprofitable effort (1929-1934), and the firm failed early in 1935.

End of the Dream

The Great Crash of 1929 and the resulting depression destroyed the 20th -century dream of automobile manufacturing in Indianapolis, but automotive parts and a single truck plant remained as important industries throughout the rest of the century while the 500-mile Memorial Day race at the flourished as the most popular one-day event in American sport. Collectors prize Marmon, Stutz, and especially Duesenberg automobiles, but Indianapolis lost its chance of leadership in the American automobile industry long before 1929. Detroit had no advantage in location, engineering talent, or skilled labor, but it did offer superior financial support and rapidly surpassed Indianapolis.

Surviving Auto Plants, 1937-2011

While early Indianapolis-based luxury automobile firms did not survive the Great Depression, the major Detroit automakers, Chrysler and General Motors, as well as Ford, established a presence in city, starting as early as the 1900s. Marmon-Herrington also survived, and the auto industry continued to be a primary employer in Indianapolis through the mid-1950s, but the industry declined during the latter decades of the 20th century. In the 2000s and 2010s, major plant closings occurred.

Marmon-Herrington

Marmon-Herrington’s financial support came from New York, but many of the staff came from Marmon Motors. Marmon-Herrington specialized in heavy-duty trucks for special services, such as hauling oil field equipment. The firm flourished during World War II, manufacturing heavy trucks and light tanks.

After the war, it continued to produce heavy-duty trucks and, from 1944 to 1956, was a major producer of trackless electric trolleybuses. Marmon-Herrington purchased Ford’s transit bus division and several school bus companies but sank into financial troubles after Herrington’s retirement. New corporate ownership diversified into other products and closed the Indianapolis factory in 1963, ending vehicle production in the city at that time.

Ford Motor Company

Ford continued to use the buildings it had erected on Washington Street for administrative purposes until 1942. From 1956-1957, Ford made plans to resume assembly operations in Indianapolis and constructed a factory on English Avenue to make steering gear assemblies for all its North American cars. The main building occupied 1,645,000 square feet of land and later was expanded to 1,900, 000 square feet. The plant also made bolts and steering gears for trucks. Ford upgraded the facility in 1992. As the automobile industry switched to electronic steering systems, however, the Indianapolis plant, which made hydraulic systems, became outmoded. The plant closed in 2008, after Ford failed to find a buyer for it.

Chrysler Corporation

In the 1910s, the American Foundry Company produced engine blocks and heads for Maxwell Motor Company, a forerunner of Chrysler Corporation, as well as for other early automobile manufacturers. Walter Chrysler took over Maxwell, and it was absorbed into his company when he established it in 1925. American Foundry continued to supply the new corporation engine blocks as it had Maxwell. American Foundry produced these components at a location on South Warman Street until it was destroyed by fire in 1930. It then operated on Naomi Street until 1944. Chrysler purchased the Naomi Street foundry in 1946 and established it as a subsidiary that made nothing but engine blocks for the parent company.

In early 1950, Chrysler built a new American Foundry plant on Tibbs Avenue. At the time, the factory presented the state of the art in automobile manufacturing. Chrysler also kept the Naomi Street location running. Construction of a Shadeland Avenue factory began in 1950, and production of automobile transmissions commenced there in 1953. In January 1959, Chrysler housed its new Electrical Division at the Shadeland Avenue location. Distributors, starters, and other electrical parts for cars became the plant’s focus.

American Foundry merged formally with Chrysler in 1959, and the corporation made a $3 million expansion to the plant, making the Tibbs Avenue factory the largest foundry in Central Indiana. It produced all V-8 engine blocks for Chrysler cars. The company quietly abandoned the Naomi Street plant, which had become outdated and obsolete, sometime in the 1970s. By the mid-1980s, the Shadeland Avenue plant also had become obsolete and closed in November 1988.

In 1996, Chrysler announced a $225 million upgrade project for the westside foundry. The expansion was designed to boost efficiency and reduce air pollution emissions. It made the Tibbs Avenue plant the “world’s largest core installation” for the manufacture of cylinder blocks, producing engine blocks and other components for Chrysler trucks and sports utility vehicles. The plant increased productivity and developed an excellent environmental record after the German automotive giant Daimler-Benz merged with Chrysler in 1998. However, Chrysler suffered major annual financial losses in the early 2000s, and the company phased out production at the site. By the time the company announced that the plant would close in 2003, it was one of only a few foundries owned by an auto company in the U.S. Chrysler shuttered the Tibbs Avenue factory in fall 2005.

General Motors Company

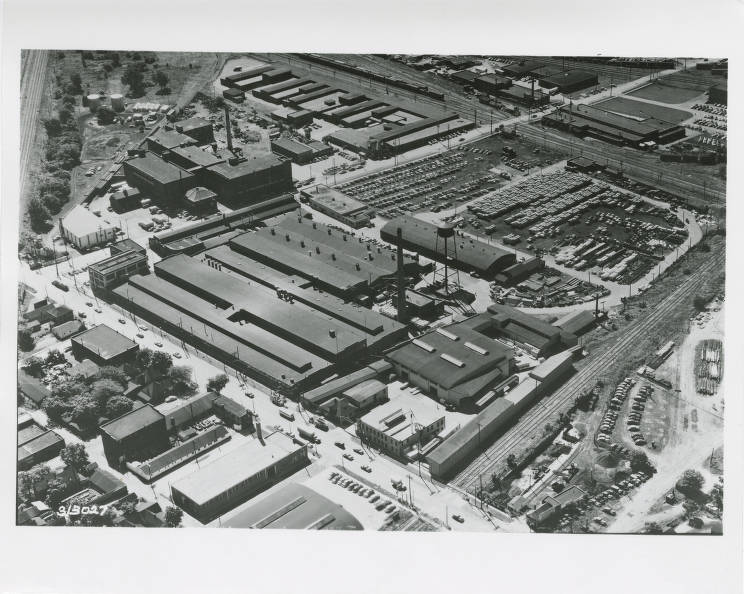

In 1930, General Motors purchased a 54-acre truck and auto-body facility, located between Harding and Oliver Avenue, from Martin-Parry Manufacturing Corporation. GM used the location as a stamping plant for Chevrolet trucks and buses. Women also made seat covers at the factory.

During World War II, the plant supplied airplane engine parts to the Pratt-Whitney Corporation, located in Buffalo, New York, and other parts to the of GM, Packard Motor Company, Rolls-Royce, Ford, and many others. It also produced ambulances for the war effort and provided over 30 types of aircraft and marine ammunition shells.

The original buildings at the plant were eventually replaced with new GM buildings. In 1964, the foremost industrial architect of the time Albert Kahn designed additions to the factory’s production bays. With these additions, the operation was scaled for 6,000 employees. By the 2000s, the number of workers employed at the plant had dropped to under 700, following a national trend. While one in three people in , Indiana, had been employed at multiple GM plants in the early 1970s, the last one had closed there in 1994, putting thousands of people out of work.

GM employed around 500,000 nationwide in the 1970s and only 52,000 by 2010. As the U.S. auto industry shrunk, GM favored stamping auto parts right next to its vehicle assembly plants. The Indianapolis stamping plant had no nearby assembly line to support, which made its survival problematic, especially as GM came close to bankruptcy with the economic downturn of 2008-2009.

Despite these circumstances, United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 23 refused to make concessions in efforts to keep the plant open. In the summer of 2010, GM entered into a deal to sell the plant to Norman Industries, a manufacturer of highly engineered machined and cast metals. This sale, however, was contingent on a new labor agreement with UAW workers that called for a cut in wages and other reductions in benefits. The members of Local 23 voted against the concession talks. Maurice (Mo) Davison, who was then Region 3 director, stepped in to negotiate the labor contract that would drop wages so that GM could sell the stamping plant. GM threatened to close the plant immediately and move equipment out of the plant if the agreement did not pass. In late September 2010, autoworkers voted nearly five to one against the contract, and the plant closed in summer 2011.

Post-2011

The departure of GM from Indianapolis left only one stamping plant, located in Marion, Indiana, and an assembly plant, in Fort Wayne, as the factories that continued to belong to this Detroit automaker in Indiana. Only two Fiat Chrysler transmission plants and one casting plant, located in Kokomo, remain. Ford has no presence in the state. In January 2021, Fiat Chrysler and Groupe PSA (French-owned Peugeot Citroën) merged to become Stellantis, forming the fourth-largest automaker in the world by volume. These plants are the only UAW-represented auto plants in the state.

There also are Japanese-owned automobile manufacturers in the state. Non-union, Indiana Automotive Fasteners, Inc., established in 1950 and owned by Japanese company Aoyama Seisakusho, operates out of , in , which is part of the Indianapolis . Subaru has an auto plant in Lafayette, which opened in 1989, and Honda Manufacturing opened in Greensburg in 2008.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.