Photo info …

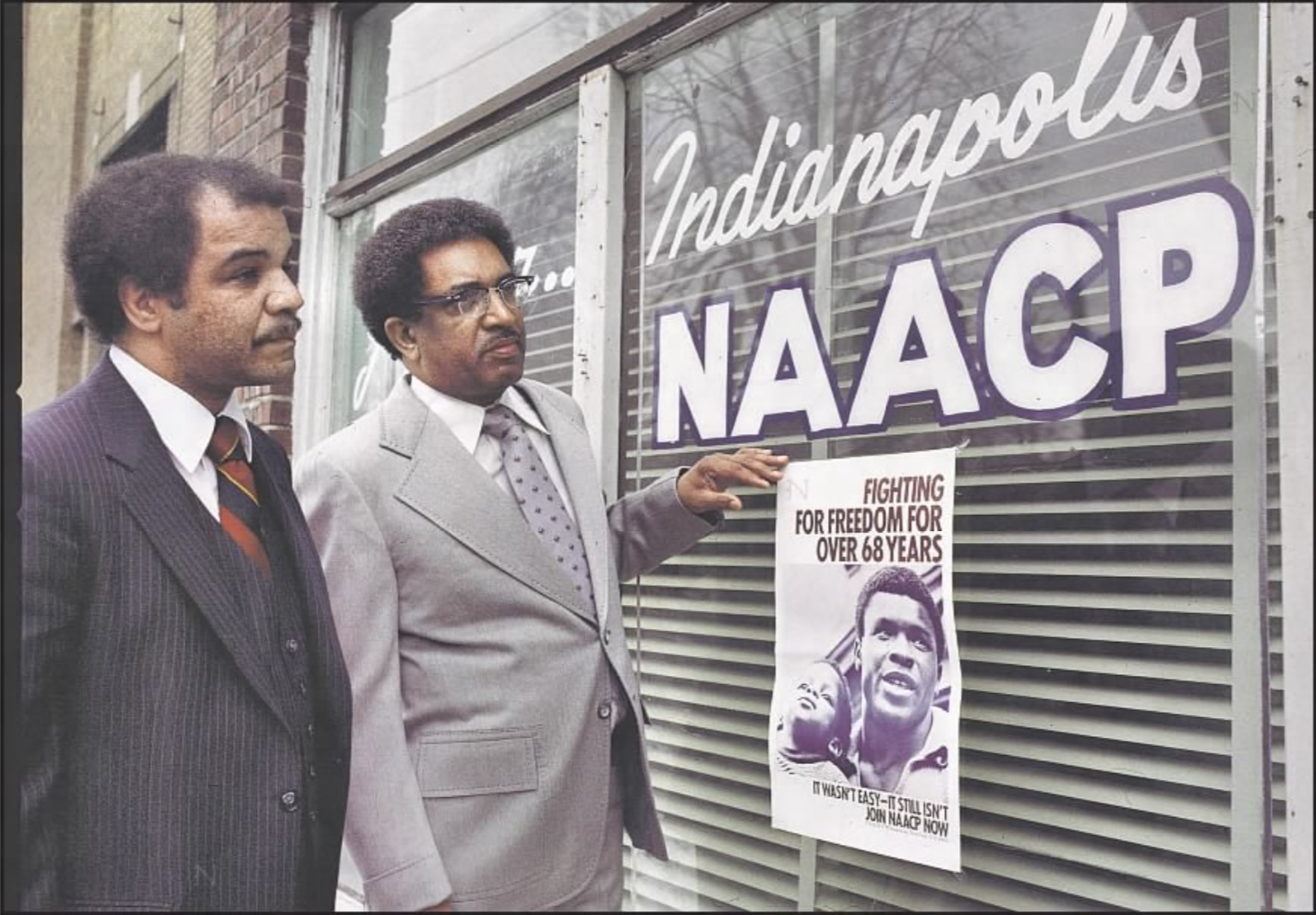

Credit: Indianapolis NewsView Source

(July 20, 1923-July 2, 2009). Aurelius Dewey Pinckney Jr. was born in Boston, Massachusetts, but grew up in Savannah, Georgia. He graduated from the school for African Americans Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in 1941 before attending Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. He later transferred to Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, where he studied chemistry.

World War II interrupted Pinckney Jr.’s education when the Army and Navy reserves were called to action. It remains unclear when Pinckney joined the Army reserves. Once the U.S. joined the war, the University of Nebraska established war-specific courses such as defense engineering and became a site of the Army Specialized Training program established by the United States Army in December 1942 to identify, train, and educate academically talented enlisted men as a specialized corps of Army officers during World War II. Pinkney initially participated in this program. Though it was integrated, the U.S. Army was not. The Army sent Pinckney to Italy with the combat engineers of the segregated 92nd Division.

Pinkney returned to Atlanta in 1945 where he resumed his education at Morehouse, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1947. He married Claragene Parks while he was in school there. The couple had two daughters and a son.

Pinkney attended the University of Chicago to begin graduate work in chemistry. The Rosenwald Fund supported Black doctoral candidates in chemistry. Pinckney, however, was not interested in becoming a college professor, and pharmaceutical companies were not in the habit of hiring of Black chemists.

Electing to study dentistry, Pinckney settled on attending another highly rated historically Black college, Howard University, for dental school due to strong family connections. Howard’s alumni networks kept its professional schools informed as to where Black doctors, dentists, and lawyers might be needed. Thus, upon graduation with his DDS in 1952, he moved to Indianapolis where he established and maintained his dental practice for more than 50 years.

Indianapolis’ segregated society did not sit well with Pinckney. As a World War II veteran, he refused to live like the repressed Black veterans of World War I had. The events unfolding in the nascent civil rights movement in the South resonated deeply with Pinckney and his friends.

Pinckney became active in Indianapolis’ branch of the . He was a tireless grassroots worker selling lifetime memberships in the organization; participating in voter registration drives; lobbying city, state, and Congressional officers; initiating or supporting court cases and civil actions; and working with youth groups and education committees. Pinckney served as president for 13 of the 20 years he was involved with the Indianapolis NAACP, finally losing his position in 1994.

During his tenure with the NAACP, he helped devise a unique school desegregation remedy involving multiple districts. He pushed for fair housing standards in , and he took on city government during a period of tumultuous police relations with the African American community.

In fact, Pinckney fought to ensure more Blacks moved into leadership roles in Indianapolis’ public service units. Joseph Kimbrew was appointed the first Black chief of the , a position he held from 1987 to 1992. In 1992, James Toler became the first Black chief of the , a position he held until 1995. Pinckney avoided confrontation when dealing with Indianapolis’ politely segregated institutions, choosing instead to build broad coalitions and use moral suasion and quiet political pressure to bring about substantive change. When criticized for the NAACP’s silence during the in Indianapolis in 1992, Pinkney remarked the organization was busy ensuring that the Black vote in Indianapolis would not be diluted because of legislative redistricting.

The Black Community did not always support Pinckney’s desegregation agenda. Some criticized his desegregation efforts with the closing of schools in Black neighborhoods that led to the busing of children to faraway schools. His drive to integrate historically white neighborhoods led others to blame him for the end of the economic and social benefits that come from living in segregated neighborhoods. His ambitious plan led to new investments, ideas, and ways of educating students and conducting business in Indianapolis. In the end, his battle to integrate schools and neighborhoods without disrupting the Black community fabric cost him friendships, family members, and personal finances. The influences of Pinkney’s political and social activism are evident throughout the works of his son Darryl Pinkney, a novelist, playwright, and essayist. The younger Pinckney’s first work of fiction (1992) is a semi-autobiographical novel about growing up in a middle-class African American family in conservative 1960s Indianapolis.

The influences of Pinckney’s political and social activism are evident throughout the works of his son Darryl Pinckney, a novelist, playwright, and essayist. The younger Pinckney’s first w high cotton (1992) is a semi-autobiographical novel about growing up in a middle-class African American family in conservative 1960s Indianapolis. In (2014) Pinckney traces the disagreements among Blacks about the best strategies for achieving equality in American society. This latter work draws a direct line from the senior Pinckney’s struggle to manage disagreements about desegregation and equality in Indianapolis that the younger Pinckney describes in the lead-up to electing the first Black president of America.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.