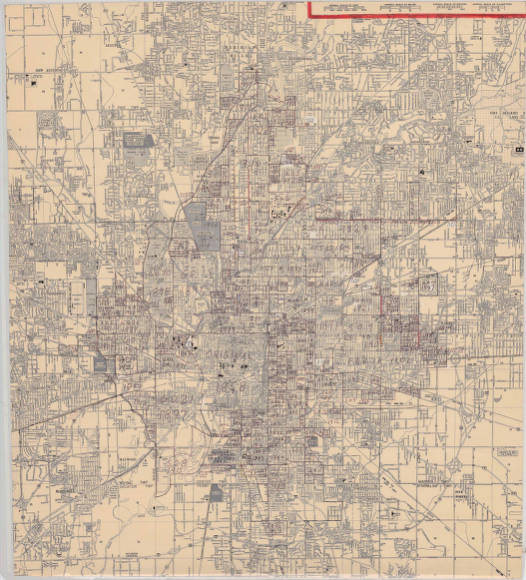

In Indianapolis, annexation involved a struggle between those in city government who saw physical growth as progress and citizens who viewed absorption into the city as a loss of autonomy and an inevitable increase in taxes. Although the city undertook a few annexations before the last decade of the 19th century, the city charter of 1891 opened the door for increased activity. Its controversial annexation provisions were the subject of protracted litigation until 1895 when the General Assembly passed an act validating them and effectively giving the City Council approval for expansion.

During this decade the city annexed the towns of , , , , and Mount Jackson. Although residents of and prevented immediate annexations of their neighborhoods (both eventually succumbed, in 1902 and 1962, respectively), the other towns requested annexation as a means of either acquiring city services or having their debt absorbed by the larger urban entity. By 1900 the area of the city had grown from 12.4 to 27.21 square miles, the largest 10-year gain experienced before the adoption of .

In the 1920s to 1940s annexations continued, as did litigation to prevent them. While the citizens of welcomed their addition to the city in 1922, residents of nearby Primrose and Rosslyn avenues unsuccessfully sued to keep their neighborhoods from being taken into the city in 1942. In the 1950s, as a means of forcing neighborhoods to surrender to annexation, the city cut off garbage collection services to remonstrating areas.

Portions of Emerson and Arlington avenues were annexed in 1952 over the protest of residents, and following litigation the Superior Court allowed the annexation of an area northeast of 38th Street. In 1952 the city grew by 180 acres due to 10 successful annexations. In 1953, however, residents of won a suit to deny Indianapolis the right to annex their town. Not long after this successful litigation, Lawrence itself began an annexation program hoping to envelop as much of the surrounding area as possible before Indianapolis could do so.

As in the 1890s, in the 1950s there were areas of the county that requested annexation in order to acquire city services. The first seven years of the decade saw six major additions totaling 28,000 persons. By 1959, Mayor was urging annexation of the entire county. That year the city appointed its first annexation director, whose assignment was to create an “orderly annexation” plan and to “sell” annexation to citizens concerned about higher taxes and school redistricting. In 1960, Indianapolis annexed 2,745 acres. The following year the state legislature settled long-time disputes between Indianapolis and Lawrence over which entity should be allowed to annex nearby lands by allowing Lawrence and other towns within four miles of Indianapolis to add land if given permission by the Metropolitan Planning Commission.

In April 1962, the city annexed the last section of that lay outside municipal boundaries. That year the Indiana Supreme Court again upheld Indianapolis’ right to incorporate outlying areas. In 1966 the city appointed , a former mayor, as annexation director, bidding him to conduct a “more vigorous” annexation program. School board president and annexation proponent Richard G. Lugar proposed a plan to separate the system boundaries from those of the city. In order to eliminate a major stumbling block in annexations, the school districts were frozen at their current boundaries. “Shoestring annexations,” adding small strips of land at the owner’s request, became the order of the day in the mid-1960s as a means of preventing remonstrances by unhappy citizens. This type of expansion allowed for land, usually owned by businesses, to be added even though it was not contiguous to the city. Although service provision for the “shoestrings” was difficult, the city used this method in order to avoid expensive lawsuits.

By the end of the 1960s, Indianapolis covered 82 square miles, and it was clear to all parties that piecemeal annexations had reached the limits of their usefulness. When Mayor took office in 1968 he aimed to eliminate the annexation question by merging the city and county. On January 1, 1970, Unigov became effective, and the remainder of Marion County was unified with the city. (Lawrence, , , and —the —retained some separate governmental functions.) The bill prohibited annexations outside the county, thus closing the story of annexations in Indianapolis.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.